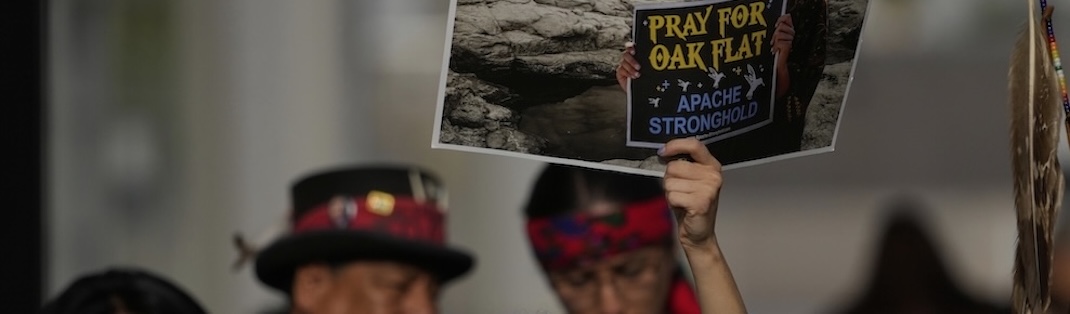

Over the vociferous dissent of Justice Neil Gorsuch, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal in Apache Stronghold v. United States. The case, which has rattled around federal courts in the Ninth Circuit for about a decade, is focused on the fate of a tract of land known as Oak Flat in Arizona. The land contains a deposit of copper that is worth billions of dollars, but to extract it would mean the permanent destruction of sacred lands that have been used by the Apache Native American tribes for more than 1,500 years.

According to the Apache, this land is a “direct corridor to the Creator” and has been the site of religious ceremonies that cannot be performed anywhere else on earth. It is not as if there is a cathedral in the next town or a synagogue on the next corner where their religious rites can be moved. The destruction of the land is synonymous with the destruction of their religion, which is older than the United States, older than many sects of Christianity, and older than Islam itself. And religious rites like this are never merely religious rites. They are repositories of cultural practice that may originate in religious belief but extend into may other areas of life. The extinction of the Apache religion will only accelerate the extinction of the Apache culture.

The Apache, unfortunately, will pay the steepest price for the decisions that have led to the present moment. But Apache Stronghold presented a now-lost opportunity for the Supreme Court not only to vindicate the First Amendment claims of the Apache but also to begin the hard work of unraveling a constitutional knot that has been decades in the making. This case sits at the intersection of civil rights, separation of powers, congressional dysfunction, and administrative power.

At different times, Oak Flat has belonged to the Apache and to Mexico; it is now part of federal lands. In 1905, it was incorporated into a national forest. President Eisenhower explicitly protected the land from mining, which was renewed later by President Nixon. Controversy over the future of the land began to emerge in the mid-1990s as mining companies began to pressure the government for access to the land—to no avail. Most recently, Obama’s National Park Service added the site to the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

Litigants in Apache Stronghold have relied upon the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) throughout the life of the case. RFRA was passed in 1993 in response to the controversial landmark religious freedom case Employment Division v. Smith. Under Smith, a law that adversely impacts religious practice passes constitutional muster if it is neutral toward the practice of religion, generally applicable to all citizens, and not motivated by animus toward religions or religious groups. RFRA requires courts to apply a more stringent standard that essentially resurrects an earlier test. Under RFRA, a law that impacts religious practice is constitutionally permissible only when it represents the least restrictive means for furthering a compelling government interest.

At the heart of Smith is the question of which government venue is the appropriate one for debate when the constitutional guarantee of free exercise of religion is at stake. It is important to note that the First Amendment is addressed to a particular branch of government: “Congress shall make no law…” (emphasis added). Under the Smith formula, courts must assume that various interests have been weighed in congressional deliberation prior to passing any law. Courts are never appropriate venues to reconsider these deliberations, which should be open and subject to democratic accountability at the ballot box.

One of the ironies of this case, however, is that under Smith the Apache would have lost much sooner. It was RFRA that kept the litigation alive. Since the mid-1990s, no fewer than 12 individual members of Congress have sponsored stand-alone bills that would have allowed for mining at Oak Flat. None of those bills gathered much support. In 2014, a last-minute rider was appended to the National Defense Authorization Act that authorized the government to trade the Oak Flat tract for a different tract and make way for copper mining.

The problem that this presents is twofold. Most fundamentally, this is a prime example of the problem with pork barrel spending. The act in question was added to an unrelated, lengthy, and complex piece of legislation by powerful members of Congress. It is not the role of a court to question whether Congress gave meaningful consideration to any piece of legislation, which in this case it certainly did not. But it is the role of those who are represented in Washington to question these practices. The deliberation that was due the Apache as their rights to religious practice collided with the interests of others was never afforded them. RFRA could have temporarily saved the day but only by bailing out lazy, feckless members of Congress in the process. RFRA is a band aid that provides for a judicial remedy to problems created by congressional dysfunction.

Second, the legal scheme has ultimately left the final disposition of all these issues to an unelected bureaucracy. For more than a century, it has been various administrative actors and agencies that have provided some form of cover for these lands and preserved the free exercise rights of the Apache from 1905 to the latest administrative action in 2016 that placed the land on the National Register of Historic Places. I am not absolutely opposed to the enabling acts by which Congress empowers administrative agencies to promulgate regulations that carry the force of law. But it seems patently obvious that the framers of the U.S. Constitution never envisioned the decisions of bureaucrats or even the decisions of administrative judges who are not subject to presidential appointment and Senate confirmation to be an appropriate means of settling controversies related to the rights of citizens enumerated in the Bill of Rights.

While the Apache are victims of negligence, it could be worse. In the tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, the Dalai Lama is the corporeal reincarnation of his predecessors. He chooses the circumstances of his reincarnation, which is only discernable to the second most significant spiritual leader of the tradition—the Panchen Lama. The Panchen Lama in turn selects the circumstances of his own reincarnation, an event that only the next Dalai Lama can recognize. The two spiritual leaders form an intergenerational cycle of spiritual continuity for followers of their faith. Eliminate one of these leaders and it is only a matter of time before Tibetan Buddhists are left with no leader with the spiritual authority to guarantee this continuity.

The Chinese Communist Party recognized this. Just three days after the Dalai Lama identified Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the reincarnation of the spirit of the Panchen Lama in 1995, the six-year-old child was kidnapped and has completely disappeared. The Dalai Lama has refused to recognize an alternative that is acceptable to CCP authorities.

And in the wake of the death of Pope Francis, the world was reminded that one of his most troubling legacies was to compromise Roman Catholic ecclesiology and agree to a mechanism by which the CCP would nominate new bishops for the pope’s approval. Cardinal Joseph Zen, Archbishop Emeritus of Hong Kong, has long been a critic of this arrangement and warned the world about the persecution of Chinese faithful, including billionaire Jimmy Lai and Bishop Peter Joseph Fan Xueyan, possibly the world’s longest-serving prisoner of conscience whose broken body was anonymously dumped on the steps of his family’s home after decades of on-and-off torture and imprisonment.

Certainly, the path to the eradication of the Apache religion has not been a state-sanctioned goal in the United States in the way that the CCP has persecuted Tibetan Buddhists and Christians. But the net effect is the same because of the very confused and inefficient way we have come to safeguard the rights of citizens. The Apache were failed by the courts, by Congress, and by administrative agencies, all of which are populated by their fellow citizens who have each pledged an allegiance to the Constitution. The decision not to hear a final appeal in Apache Stronghold is a “grievous mistake,” according to Justice Gorsuch, “with consequences that threaten to reverberate for generations.” Those consequences are existential for the Apache but may prove to be pernicious for the rest of us, too, if we refuse to do the work required to restore a properly ordered constitutional system.