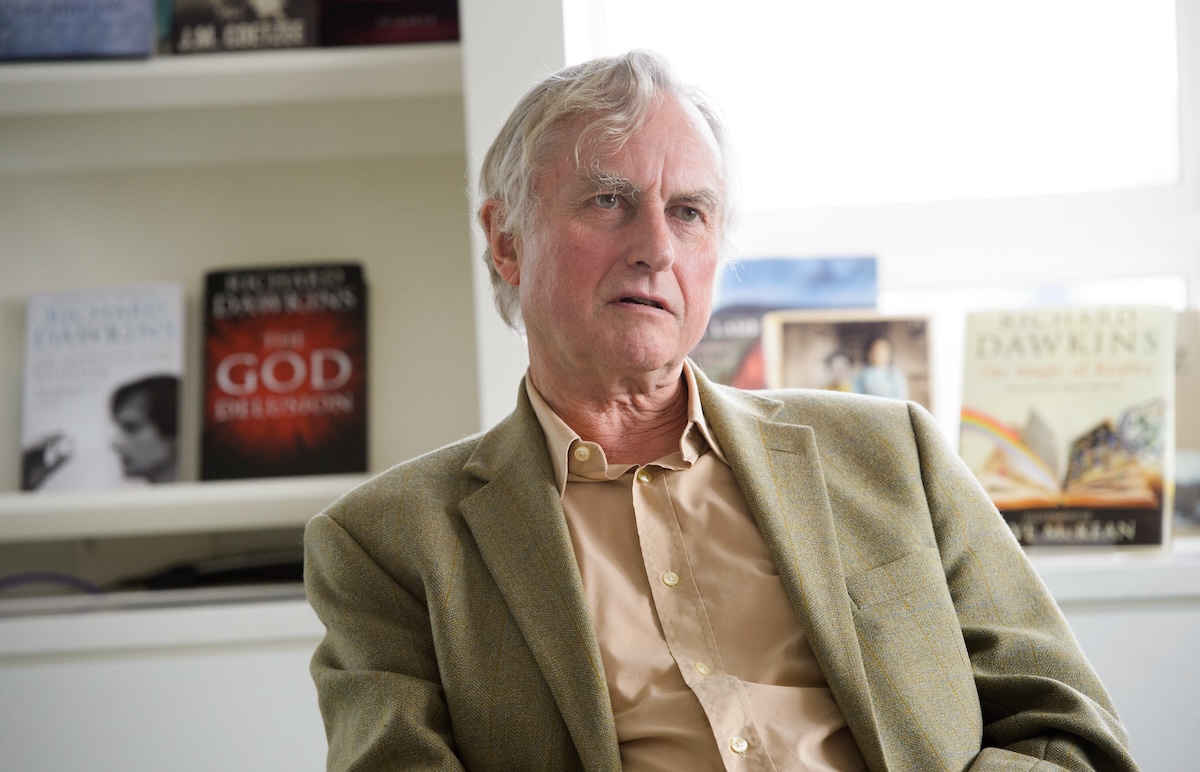

On April Fool’s Day, I saw headlines that Richard Dawkins, the famed British atheist and evolutionary biologist, had claimed to be a “cultural Christian.” I assumed the headlines were clickbait consistent with the day’s theme. But, no—he did make this claim in an interview with LBC’s Rachel Johnson on Easter Sunday. Dawkins said he was happy to hear that the number of people who believe in the claims of the Christian faith is declining, but he was quick to add that he would not be happy to lose cathedrals, parish churches, and Christmas carols. It would also be “truly dreadful” to substitute Christianity for any other faith, namely Islam, as the religion that informs the culture of England. Christianity is, according to Dawkins, a “fundamentally decent religion in a way that Islam is not.”

During this Easter interview, Dawkins offended the two largest religious groups in the United Kingdom. But he noted, even if begrudgingly, something that many in the West seem to have missed—that religion provides the foundational set of ideas from which culture emerges. And from that, social institutions, even political ones, emerge in way that at once reflects and preserves that culture. This is true of Anglican Christianity in the United Kingdom, Roman Catholic Christianity in Poland, Islam in Turkey, and Buddhism in Japan. Dawkins apparently prefers the type of culture that rises from soil fertilized with Christian ideas and would opt for that “every time” when presented with a choice between Christianity and Islam.

England would be dramatically different today had it not been Christianized. Christianity has played a significant role in shaping Western culture to the extent that even disparate parts of the Christian world share similarities, even if different languages, customs, and people mediate them. Even 400 years ago, a person able to travel between them would notice common cultural characteristics in Anglican London, Catholic Warsaw, and Orthodox Belgrade that would be absent in Baghdad or Bangkok. This is not to say that Christianity does not have internal divisions that are the source of political strife. But common civilizational distinctives develop in very different Christian cultures given the common aspects of the broader Christian faith (i.e., creeds, history, and religious texts). This is part of what makes the intra-Christian political strife so ridiculous. But it is also these things that Dawkins identifies as attractive.

I suppose Dawkins’ remarks could be interpreted as a softening toward religion. But he insults religious belief and attacks Islam as being fundamentally indecent. This is consistent with a long career marked by a failure to take religious belief or religious believers seriously. He’s called religious catechesis a form of child abuse and has been criticized even by fellow atheists as an “anti-religious missionary”; they have even compared the methodology of his work to religious fundamentalism. I tend to agree with this assessment of him and his latest remarks for a few reasons.

First, Dawkins has made a mistake that Martyn Lloyd-Jones called “the tragedy of the last hundred years.” Many of our civilizational ills have “been due to the fallacy of imaging that you [can] shed Christian doctrine but hold on to Christian ethics.” The cathedrals and parish churches of Europe reflect the beliefs of those who built them, and Christmas carols are the musical expressions of the deeply held beliefs of Christians. Dawkins appreciates these things merely as the artifacts produced by unsophisticated men grasping at superstitious beliefs that make it easier to suffer, experience loss, and die. Dawkins does not recognize or is not concerned with the condescending elitism of his eagerness to enjoy the fruits that represent the creative work or material sacrifice of those he deems naïve enough to believe the unbelievable claims of the Christian faith. These artifacts make Dawkins feel at home, whereas the 6,000 mosques being built around Europe are “truly dreadful” and provide a cause for alarm.

But why? If mosques and churches are merely artifacts built by primitives in thrall to superstitious beliefs, why be concerned? It is not the difference in architecture that bothers Dawkins—it is the difference in the religious beliefs that animate those who build the buildings that he finds problematic. He is alarmed, justifiably or not, because he recognizes the inescapable link between religious beliefs and cultural and social institutions. He has a clear preference for the type of culture and institutions produced by one over the other.

Second, Dawkins prefers religious hypocrites. I am not a Muslim myself, so I cannot comment on the proper interpretation of Islamic texts. But he differentiates between the holy texts of Islam and “individual Muslims, which are quite different” regarding “active hostility toward women” and homosexuals. If that is the case, then why would a Muslim majority in England be such “a terrible thing”? He supports Christianity as a “bulwark against Islam” even as he dedicates his life to gutting Christianity of any meaning. If individual Muslims do not actually reflect the Islamic faith, then why not be a “cultural Muslim” rather than a “cultural Christian”?

Third, with the rise of Islam in Europe, it seems that Dawkins would take note of the sharp decline in Christianity in the West and move on to the eradication of the “pernicious nonsense” of the supernatural claims of Islam with the same missionary zeal. I don’t doubt that Dawkins finds all religious claims to be inherently illegitimate, but why does he attack the substance of Christianity but the existence of Islam?

Dawkins has highlighted a couple of pressing existential issues that the West must grapple with soon. First, religion matters. Maybe more fundamentally, metaphysics matters. In the words of an ethics professor I once had, “Metaphysics is everything.” Christianity has been part of the civilizational DNA of the West from the start, and it is impossible to know what will happen if those so inclined are successful in eradicating it from the public square. Even the concept of a political or social right is traceable to the Christian tradition, so to the extent that our public discourse is focused on rights, it bears a Christian mark, as Pierre Manent describes it.

So, yes, we should be concerned about the decline of Christianity in the West, but for reasons much more fundamental than our preferences for Christmas carols and cathedrals. Christian norms and mores have created imperfect societies and social institutions, but they are places where non-Christians have been welcomed and able to flourish in ways that are unprecedented in other parts of the world. All people, Christian or not, should appreciate this aspect of cultural Christianity.

But we have also seen in recent months that we must take seriously the task of figuring out how to live in a plural society alongside people who are different. The encampments on America’s university campuses and the marches in the streets of European capitals are not “mostly peaceful protests” seeking justice. Different people participate for different reasons. These are alarming displays of societal fracture and a rejection of the civilizational norms that have marked the West for hundreds of years.

These protests are not caused by Muslims per se but by the new reality that the West is not dominated by one faith any longer. So the challenge that Muslims present to the West is the challenge of living in a plural society that was once homogenous. As Pierre Manent has written, this is a matter of “granting a place [in a Christian society] to a form of life with which [Christianity] has never mixed on an equal footing.” This is not an impossible and unsolvable challenge, but one that will require a great deal of openness and honesty on the part of all of us—Christian, Muslim, Jew, and the religiously unaffiliated.

Richard Dawkins has once again proved to be more of a provocateur than an illuminator of solutions. Learn from him an appreciation of the cultural and social fruits of religious devotion, but ignore the lessons about disdain for the religiously devoted.