According to a recent report from the U.S. Census Bureau, the values and priorities of young adults are shifting dramatically from those of generations past, particularly when it comes to work, education, and family.

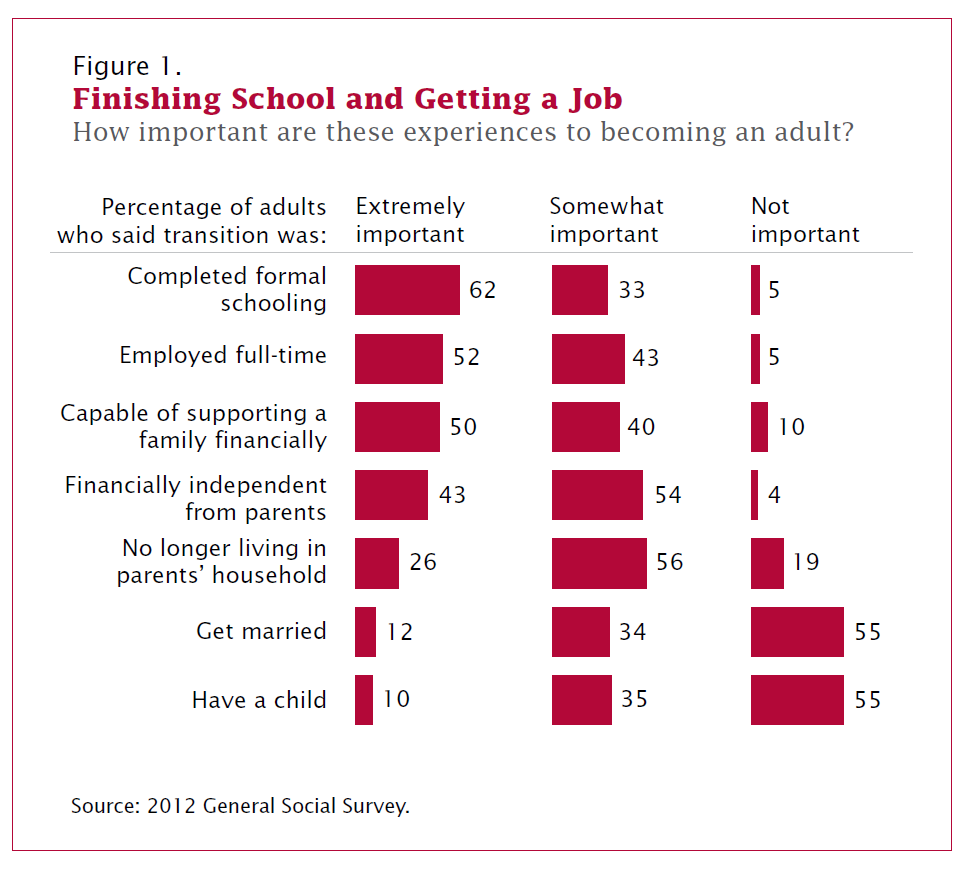

“Most of today’s Americans believe that educational and economic accomplishments are extremely important milestones of adulthood,” the study concludes. “In contrast, marriage and parenthood rank low: over half of Americans believe that marrying and having children are not very important in order to become an adult.”

Comparing young adults between 1975 and today (2012-2016), the study highlights a range of shifts in the popular views on what it means to “become an adult,” as well as what’s most important and formative throughout that process.

As shown on the following chart, respondents demonstrated a clear preference for full-time work, education, and economic stability well before marriage and family-rearing. (The study defines young adults as 18- to 35-year-olds.)

“What is clear is that most Americans believe young people should accomplish economic milestones before starting a family,” the study says.

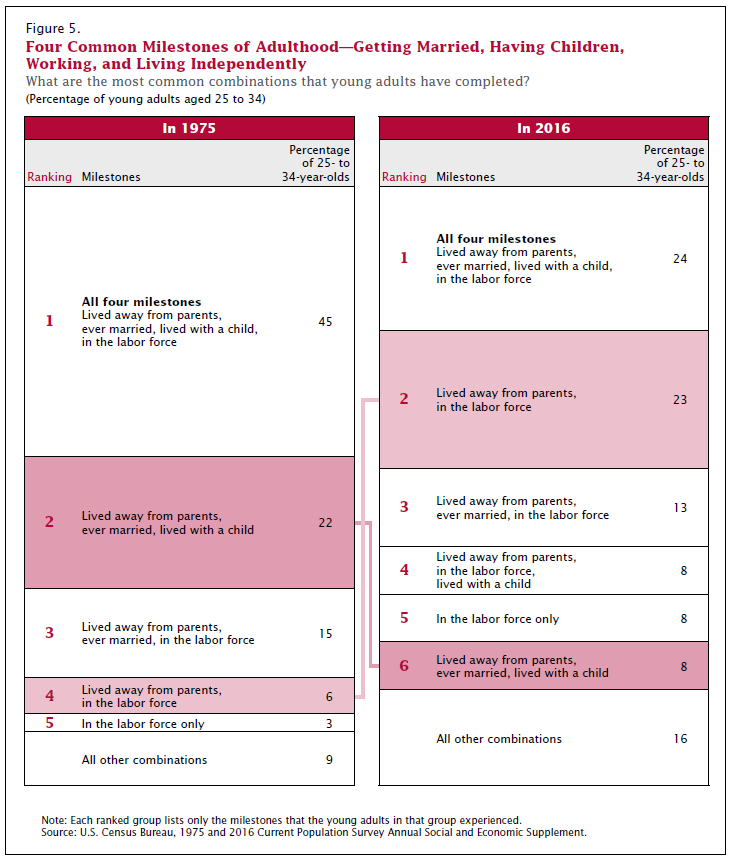

Observed another way, we can see the shift by looking at four key milestones — “getting married, having children, working, and living independently” — from generation to generation.

Alas, the Census study only affirms what University of Virginia sociologist Bradley Wilcox and his fellow researchers have been highlighting for some time now.

“Culturally, young adults have increasingly come to see marriage as a ‘capstone’ rather than a ‘cornerstone,’” they write, “that is, something they do after they have all their other ducks in a row, rather than a foundation for launching into adulthood and parenthood.”

For Wilcox and his colleagues, the shift has surely led to certain gains, but overall and in the long run, the trend toward delayed marriage is likely to accelerate the fragmentation of American society.

“We believe that marriage is not for everyone, be they twentysomething or some other age,” they write. “Nevertheless, the decoupling of marriage and parenthood represented by the Great Crossover is deeply worrisome. It fuels economic and educational inequality, not to mention family instability, amid the rising generation.”

Indeed, what at first seems like a welcome development in economic and educational progress has its roots in a view of progress that’s fundamentally backwards. What might we lose if we, as a society, tend toward putting it last, and not first, treating family and children as a “crowning achievement” (Wilcox’s words) vs. a foundation or a starting point for civilizational success?

In response to these changes, Wilcox recommends “a comprehensive approach, encompassing economic, educational, civic, and cultural initiatives, to help twentysomething men and women figure out new ways to put the baby carriage after marriage.” But while there are plenty of institutional adjustments that we can and should consider, we can begin by simply remembering (and calling unto remembrance) the formative, transformative power of the family.

As children, the family sets the stage for our service and the scope for our gift-giving, both in work and play. It is in the family where we first learn to love and relate, to order our obligations, and to orient our activities toward others. It is in the basic, mundane exchanges between parent and child, brother and sister, that we learn what it means to truly flourish.

As spouses, marriage brings its own variety of personal and relational formation, offering unique lessons on love and covenant, sacrifice and obligation, freedom and duty.

And as parents, the family has a remarkable “reforming power,” wielding an inescapable and irresistible mix of moral, social, and spiritual transformation. The delay in child-bearing may indeed be dangerous when it comes to impending demographic collapse, but that’s not even considering the “formation” vacuum we’re bound to see among the adults that are already inhabiting our social and economic landscape.

As Herman Bavinck explains in his book, The Christian Family, “The family is a school for the children, but in the first place it is a school for the parents”:

[Children] develop within their parents an entire cluster of virtues, such as paternal love and maternal affection, devotion and self-denial, care for the future, involvement in society, the art of nurturing. With their parents, children place restraints upon ambition, reconcile the contrasts, soften the differences, bring their souls ever closer together, provide them with a common interest that lies outside of them, and opens their eyes and hearts to their surroundings and for their posterity. As with living mirrors they show their parents their own virtues and faults, force them to reform themselves, mitigating their criticisms, and teaching them how hard it is to govern a person.

The family exerts a reforming power upon the parents. Who would recognize in the sensible, dutiful father the carefree youth of yesterday, and who would ever have imagined that the lighthearted girl would later be changed by her child into a mother who renders the greatest sacrifices with joyful acquiescence? The family transforms ambition into service, miserliness into munificence, the weak into strong, cowards into heroes, coarse fathers into mild lambs, tenderhearted mothers into ferocious lionesses. Imagine there were no marriage and family, and humanity would, to use Calvin’s crass expression, turn into a pigsty.

The family isn’t the only place we can learn these lessons, of course. But up until recently, these basic lessons have been largely “built in” to the human experience, and at a much earlier age.

Such reminders needn’t point us toward one-size-fits-all mandates or blueprints for when or whether people should marry or have children. But they ought to remind us of what’s at stake, and that the family is more than a “crowning achievement” or a prize received after a life lived well.

As young adults continue to ponder and asses the importance of various formative “milestones,” and as we seek to prioritize them, in turn, we’d do well to simply pause and remember the “reforming power” of the family, and the joy and freedom it has to contribute to all else – economic, educational, or otherwise.

“Family is the first and foundational ‘yes’ to society because it is the first and foundational ‘yes’ to our nature,” as Evan Koons explains in For in the Life of the World, “to pour ourselves out like Christ, to be gifts, and to love….In family, our character is formed and given to the world.”