Who’s going to win big at the Oscars? I know: Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another, its title taken from a statement published in 1969 by the revolutionary-terrorist organization the Weather Underground. It’s the only “Oscars movie” we had in 2025, certainly the most talked about movie of the fall season. It received great praise for the way it glorified its fictional black terrorists. Writers at renowned publications had the chance to rehash radical chic, to connect the murderous radical politics of the “days of rage,” which closed out the 1960s and opened the ’70s, to the BLM/woke/ICE era.

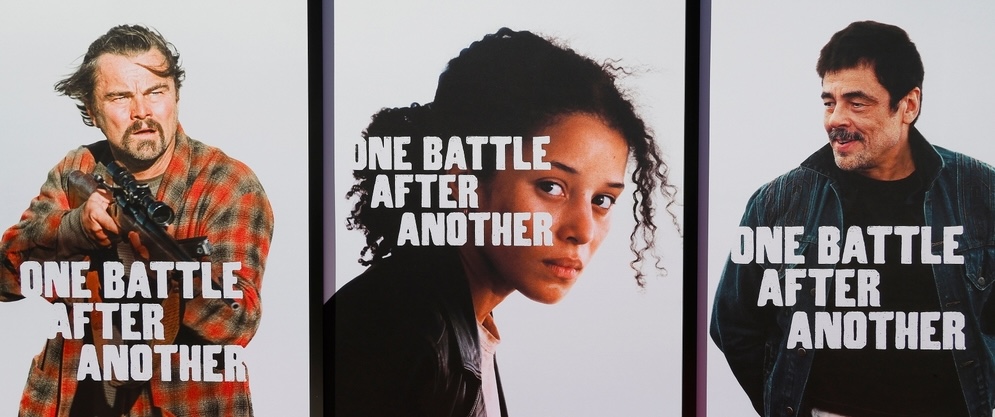

Anderson gave liberals, Progressives, and other lefties of the world reason to unite in an attempt to marry moralism to glamour. One Battle After Another offers them a terrorist organization named after a cocktail, the French 75, apparently led by a lady named Perfidia (Teyana Taylor), who believes in abortions and sexual provocation, whether involving fellow terrorist Pat (Leonardo DiCaprio) or Col. Lockjaw (Sean Penn). Meanwhile, a secret organization among the elite is enforcing racial purity.

If this sounds nuts, well, that’s to be expected of an adaptation of a Thomas Pynchon novel: Vineland (1990), a story about hippies revolting against fascism in Southern California. But Anderson’s best movie, Inherent Vice (2014), was also an adaptation of a Pynchon novel (2009), about the self-destruction of the hippies in California at the end of the 1960s, so that wouldn’t by itself be disqualifying. In Inherent Vice, drugs were the sign of freedom turning into death. In One Battle After Another, it’s radical politics. Pynchon, by the way, published another novel last year, Shadow Ticket, at the age of 88. Perhaps his last.

DiCaprio looks ready to win his second Oscar for playing an idiot who is good at making bombs; he’s the female half of a couple, the male half of which is played by Perfidia (yes, you read correctly). He’s stuck with a child that might not be his, she murders a black security guard during a robbery, then the terrorism stops once Perfidia is captured by Lockjaw and betrays her revolutionary comrades. That’s the clampdown, end of Act One, which takes about half an hour.

The next two hours of the movie are set 16 years later, when the baby has grown up into a remarkable young woman called Willa (Chase Infiniti), raised by DiCaprio, who has been rendered comically ineffective by years of smoking marijuana. The plot is simple: Willa is chased by evil government agent Lockjaw and protected by the former terrorists. DiCaprio tries to find her, with help from her karate sensei (Benicio del Toro). During the chase, we see BLM riots and illegal aliens being compared to black slaves in that they’re now traveling a new “underground railroad.”

Altogether, One Battle After Another gives us the only sustained caricature of the left-wing vision of America in quite a long time. I wouldn’t want to jump to conclusions about Anderson’s politics, but I hazard the guess that the caricature is inadvertent. The evils of white men, the fantasies of ethnic-minority racial solidarity and female strength against an oppressive government—everything in the hippie vision is on display, albeit reduced to absurdity. We see the ordinary America of the time rendered surreal by enthusiasms and hysterias that had a power over many people in the 1960s but that don’t now (or not in the same way, as bombings at least have fallen out of fashion).

However, within the mad world of revolution, One Battle After Another is the story of a father trying to save his daughter. The failure of the revolution and the disappearance of Perfidia ruined what was already a weak man, capable only of becoming excited by what harsher, more passionate people made him do. Without them trying to get everyone killed, he is barely alive. The loss of his daughter brings urgency back into his life and, for once, he’s acting in order to save someone he loves, not destroy someone he hates.

Family is the limit to ideology. Usually this appears as a vulnerability in One Battle After Another, something the terrorists can be threatened with when they are captured by the authorities. We see terrorists who are willing to face death and eager to commit murder, but they also will give up their comrades, their cause, to save their family. This is the core teaching of the movie.

What’s strange is that the movie is against the revolution. At the end, Willa risks turning into her mother, indeed, not recognizing her own father. She has by that point killed a man, in self-defense. All her strength might corrupt her; indeed, she could go mad. Her ineffective father is no help when she’s in danger, but manages to come to her aid when her soul is in danger. He even shows her, finally, a letter from her mother that expresses regret for her youthful madness—which is what put the girl in such danger in the first place.

One Battle After Another has all the benefits of a big budget (about $140 million), which we may say was burned in an act of revolutionary aestheticism. The movie grossed only around $70 million at the American box office. But it’s expertly made, which is rare nowadays. From the VistaVision cinematography of Michael Bauman, who’s been shooting Anderson’s movies since Phantom Thread, to the music of Jonny Greenwood, who’s been scoring them since There Will Be Blood, Anderson remains in full control of the movie, which he also produced.

I wonder, however, whether all this effort wasn’t wasted, regardless of what I expect will be an Oscar win—which Anderson has long deserved, yet it has eluded him for all his 11 nominations. Unfortunately for him, though, the movie’s liberal audience is not interested in learning about family love; they want the fantasy of revolutionary violence as we see in the streets of “sanctuary” cities. And the people who care about family have no interest in watching a movie that seems to glorify terrorists. Quite the dilemma for the filmmaker. But doesn’t that also capture the present moment perfectly?