July 10 is the 100th anniversary of the Scopes “monkey trial” in Dayton, Tennessee. Some pundits will praise the trial as a public relations victory for both evolution and famed lawyer Clarence Darrow, who claimed, “The fear of God is not the beginning of wisdom. The fear of God is the death of wisdom.” In journalism history, though, the 1925 trial was when mocking the Bible went mainstream.

Let’s set the scene. By the 1920s, many academic leaders accepted the theory of evolution as scientific fact. Belief in evolution provided new hope for those who no longer accepted biblical Christianity. As the New York Times editorialized, modern man needed “faith, even of a grain of mustard seed, in the evolution of life.” The Times quoted Bernard Shaw’s statement that “the world without the conception of evolution would be a world wherein men of strong mind could only despair”—for their only hope would be in a God to whom modernists would not pray.

Other newspapers also highlighted evolutionary beliefs, given new impetus by the Great War, which so decimated hopes for peaceful progress that millions came to believe in one of two ways upward from misery: God’s grace or man’s evolution. The New York Times’ hope was in evolution. An editorial stated: “If man has evolved, it is inconceivable that the process should stop and leave him in his present imperfect state. Specific creation has no such promise for man. … No legislation should (or can) rob the people of their hope.”

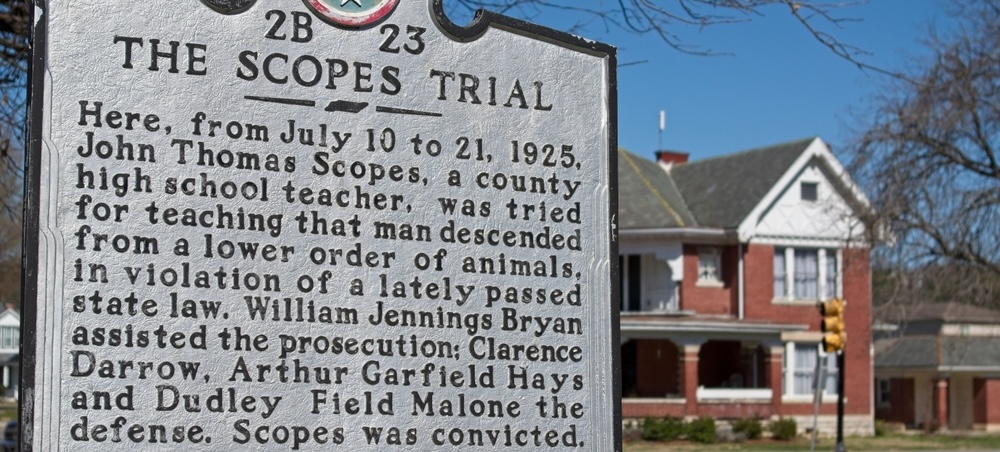

But Tennessee lawmakers tried to do just that. The state’s legislators did not ban teaching about evolution, but they made it a misdemeanor for public school teachers to proclaim as truth the belief “that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” One young Dayton teacher, John T. Scopes, responded to an American Civil Liberties Union search for a defendant in a test case, with the ACLU paying all legal expenses. The ACLU hired Darrow, the most famous lawyer of the era, to head the defense. Fundamentalist William Jennings Bryan, thrice-defeated Democratic presidential candidate and former secretary of state, became point man for the prosecution.

The issue and the luminaries brought out the journalists. More than 100 reporters were at the trial that began on July 10. They wired 165,000 words daily to their newspapers during the 12 days of extensive coverage. The New York Times itself received an average of 10,000 words per day from its writers on the scene.

In theory, trial coverage was an opportunity to illuminate the theological bases on which both evolutionist and creationist superstructures rested. The trial transcripts show that intelligent people (and not-so-intelligent people) were on both sides of the issue. Journalists, though, typically described the story as one of pro-evolution intelligence vs. anti-evolution stupidity. H.L. Mencken, conservative on some issues but radical on religion, attacked the Dayton fundamentalists (before he had set foot in the town) as “local primates,” “yokels,” “morons,” and “half-wits.”

Mencken warned that “Neanderthal man is organizing in these forlorn backwaters of the land, led by a fanatic, rid of sense and devoid of conscience.” He summarized the debate’s complexity by noting, “On the one side was bigotry, ignorance, hatred, superstition, every sort of blackness that the human mind is capable of. On the other side was sense.” Nunnally Johnson, who covered the trial for the Brooklyn Eagle and then became a noted Hollywood screenwriter, described the press corps at the trial: “Being admirably cultivated fellows, they were all of course evolutionists and looked down on the local fundamentalists.”

Such ridicule was not a function of politics: It underlay the politics of both liberal and conservative newspapers. The liberal New York Times editorialized that evolutionist opponents represented a “breakdown of the reasoning powers. It is seeming evidence that the human mind can go into deliquescence without falling into stark lunacy.” The conservative Chicago Tribune sneered at fundamentalists looking for “horns and forked tails and the cloven hoofs.”

The Tribune reported that the Tennessee law, if upheld, would make every work on evolution “a book of evil tidings, to be studied in secret.” That was nonsense: Hundreds of pro-evolution writings were on sale in Dayton. Even a drugstore had a stack of materials, representing all positions. The key issue was not free speech but parental control over school curricula. Even in Tennessee, Christian parents already sensed an exclusion of their beliefs from schools they funded.

Instead of reporting the reality, the New York American began one trial story with the sentence, “Tennessee today maintained its quarantine against learning.” The battle pitted “rock-ribbed Tennessee” against “unfettered investigation by the human mind and the liberty of opinion which the Constitution makers preached.” Reporters from the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune regularly attacked Christian faith and “this superheated religious atmosphere, this pathetic search for the ‘eternal truth.’”

One of the most famous journalists of the era, Arthur “Bugs” Baer, wrote with lively viciousness. He depicted Scopes as an imprisoned martyr, “the witch who is to be burned by Dayton.” (Actually, Scopes did not spend a second in jail and regularly ate dinner at the homes of Dayton Christians.) Baer predicted that a fundamentalist victory would turn “the dunce cap [into] the crown of office.” Baer called residents of Dayton “treewise monkeys” who “see no logic, speak no logic and hear no logic.”

Other headlines screamed regarding the Dayton jurors: “INTELLIGENCE OF MOST LOWEST GRADE,” since “all twelve are Protestant churchgoers … Hickory-shirted, collarless, suspendered, tanned, raw-boned men are these.” One prospective juror even had “a homemade hair cut and ears like a loving cup.” The New York Times worried about the belief in creationism by “thousands of unregulated or ill-balanced minds” and depicted as zombies Tennesseans entering the courthouse: “All were sober-faced, tight-lipped, expressionless.”

The formal judicial proceedings were not the main show. The Scopes case was open-and-shut, with the ACLU desiring conviction on obvious law-breaking so that the decision could be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court for a ruling on the Tennessee act’s constitutionally. (Ironically, after Scopes’ conviction, the Tennessee Supreme Court upheld anti-evolution law but overturned the conviction on a technicality involving the imposition of a $100 fine without jury approval. The U.S Supreme Court never heard the case.) The importance of the Dayton trial, for both prosecution and defense, lay in the chance to debate issues.

The highlights were two debates, one on July 16 between Bryan and Darrow associate Dudley Malone, and the other on July 20 between Bryan and Darrow himself. The court transcript shows strong and intelligent orations by both sides. Bryan, within biblical presuppositions, made a logical and coherent argument. He stressed the evolutionary theory’s lack of scientific proof and emphasized its inability to answer questions about how life began, how man began, how one species actually changes into another, and so on. Malone, within evolutionist presuppositions, argued in a similarly cohesive way.

Both sides did well, but that’s not what readers of most major newspapers would see. The typical report tracked Mencken’s gibe that Bryan’s speech was a “grotesque performance and downright touching in its imbecility.” The New York Herald Tribune told of how Bryan “was given the floor and after exactly one hour and ten minutes he was lying upon it horizontally—in a figurative sense.” (William O’Connell McGeehan, regularly a sportswriter, did not often get to write about figurative self-knockouts.)

Many reporters loaded their Bryan coverage with sarcastic biblical allusions, as in “The sun seemed to stand still in the heavens, as for Joshua of old, and to burn with holy wrath against the invaders of this fair Eden of fundamentalism.” Sometimes sentence after sentence mixed biblical metaphors: “Dayton began to read a new book of revelations today. The wrath of Bryan fell at last. With whips of scorn, he sought to drive science from the temples of God and failed.”

The second major confrontation came on the trial’s last day, when Bryan and Darrow battled in a debate bannered in newspapers across the country: “BRYAN AND DARROW IN BITTER RELIGIOUS CLASH.” The trial transcript shows a presuppositional debate in which both enunciated their views with occasional wit and frequent bitterness. If the goal of the antagonists in the Tennessee July heat was to keep their cool, both slipped, but it was Darrow who showed extreme intolerance, losing his temper to talk about “fool religion” and to call Christians “bigots and ignoramuses.”

Once again, though, New York and Chicago-based reporters declared Bryan a humiliated loser. The New YorkTimes called Bryan’s testimony “an absurdly pathetic performance, with a famous American the chief creator and butt of a crowd’s rude laughter.” The next day, the Times observed, “It was a Black Monday for [Bryan] when he exposed himself. … It has long been known to many that he was only a voice calling from a poorly-furnished brain-room.” The Herald Tribune’s McGeehan wrote that Bryan was “losing his temper and becoming to all intents and purposes a mammal.”

Overall, the coverage is an example of what the leading columnist of the era, Walter Lippmann, wrote in 1921 about “the pictures in our head,” the phenomena we want to see: “For the most part we do not see first, then define; we define first and then see.” Lippmann gave one jocular example of how a traveler’s expectations dictate the story he will tell upon return: “If he carried chiefly his appetite, a zeal for tiled bathrooms, a conviction that the Pullman car is the acme of human comfort, and a belief that it is proper to tip waiters, taxicab drivers, and barbers, but under no circumstances station agents and ushers, then his Odyssey will be replete with good meals and bad meals, bathing adventures, compartment-train escapades, and voracious demands for money.”

Reporters often seemed to watch the pictures in their head rather than the trial in front of them. One New York scribe, under the headline “Scopes Is Seen as New Galileo at Inquisition,” even wrote that the

sultry courtroom in Dayton, during a pause in the argument, became hazy and there evolved from the midst of past ages a new scene. The Tennessee judge disappeared and I racked my brain to recognize the robbed dignitary on the bench. Yes, it was the grand inquisitor, the head of the inquisition at Rome. Lawyers faded from view, all except the evangelical leader of the prosecution, Mr. Bryan, who was reversely incarnated as angry-eyed Pope Urban. … I saw the Tennessee Fundamentalist public become a medieval mob thirsty for heretical blood. … [It was] 1616. The great Galileo was on trial.

Overall, Scopes trial coverage provides an example of philosopher Cornelius Van Til’s contention that all views are essentially religious, in that they are based on certain convictions as to the nature of the universe. Readers of every news story are not only receiving information but are being taught, subtly or explicitly, a particular worldview. In Kantian terms, newspapers offer not only phenomena but noumena; not only facts learned from study but an infrastructure that gives meaning to those facts.

It’s 2025, and nothing much has changed.

(This essay was edited from a 5,000-word academic article originally published in American Journalism, Summer 1987.)