When considering the many woes of modern Western civilization, classicist Spencer Klavan, in How to Save the West, elaborates on the five main crises contributing to today’s decline: the crisis of reality, the body, meaning, religion, and regimes. In Klavan’s analysis, most Westerners ignorantly feel their way through life and allow vast impersonal forces to determine what they see, believe, think, feel, and do.

While Klavan’s book does an excellent job of diagnosing the problem (of which I write about here), his prescriptions mostly involve acknowledging the situation, reading the classics, and not being a phony. This is fine advice, but it doesn’t go far enough. People today need more than a little tough talk and some heady tomes; they need a complete intellectual revival. To that end, they need to learn philosophy.

As it stands, every Westerner, and especially every Christian, sits atop a mountain of wisdom collected throughout the centuries, even millennia. Brilliant men and women have developed powerful systems of thought that enabled ever-greater understandings of the world. Sadly, outside a small group of scholars and enthusiasts, most people have never encountered these geniuses nor truly experienced the difference their ideas could make in their lives.

To be fair, picking up a book of philosophy is a daunting task. Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason or Heidegger’s Being and Time is not exactly a light read to enjoy on the beach, nor does there seem to be much point to reading Descartes’s Meditations when studying to become a mechanical engineer. For too many people, philosophy is too difficult and too impractical to bother with.

Fortunately, philosophy professor and writer Peter Kreeft has written a comprehensive overview of Western philosophy, Socrates’ Children, that addresses these challenges without compromising the profundity and complexity of his subject. His four-volume series offers an in-depth summary of the hundred most important philosophers, starting from the pre-Socratics and founders of the great religions all the way to the academics and writers of the 20th century. As he puts it in his “Salesman’s-Pitch” at the beginning of each volume, his aim is to tell “the dramatic story of the history of philosophy, the narrative of the ‘great conversation,’ which you find in the ‘great books.’”

As with his other books, particularly his classic Socratic Logic, Kreeft doesn’t just inform and entertain his readers; he teaches and engages them. This is what sets his series apart from other history of philosophy books that typically offer a brief biography, a simplified paraphrasing of the philosopher’s ideas, a few pop-culture references, and a fun, relatable hypothetical scenario or two. By contrast, Kreeft employs his encyclopedic knowledge of philosophy by featuring samples of the philosopher’s writings, a systematic analysis of key arguments along with the objections made to those arguments, and the logical and historical context of each philosophy.

True, working one’s way through each volume is not exactly easy, particularly when reading about the ontology of St. Thomas Aquinas or anything from the German idealists, but it succeeds in training even the dullest of minds and thereby helps one live a more rational and fulfilling life. All it takes is some patience, persistence, and a willingness to ask big questions.

It also helps to go in order to see how each philosopher builds on the one before. Kreeft accordingly begins with mystics and prophets like King Solomon, Gautama Buddha, Adi Shankara, and Confucius, each of whom set the stage for seeking wisdom in their respective cultures. He then moves on to the predecessors of Socrates, like Thales, Heraclitus, and Pythagoras, who began to develop theories on the nature of reality (metaphysics). Perhaps to the surprise of moderners who take the opposite view, philosophy at the beginning of history combined spirituality, theology, science, ethics, and even mathematics in unexpected and inventive ways.

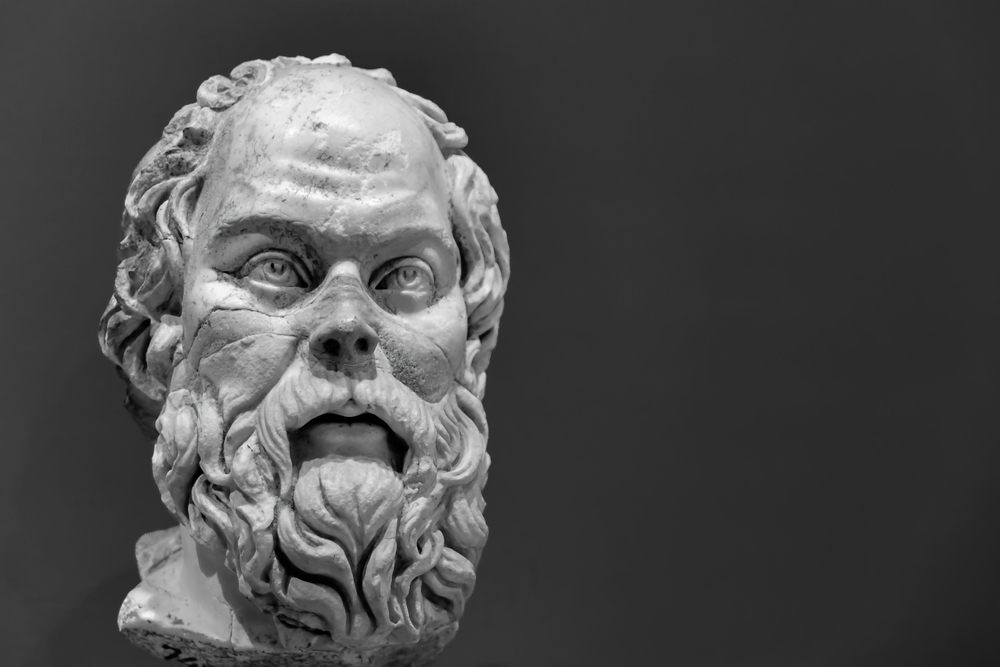

The eponymous hero of the series, Socrates, finally enters the picture and converts this contradictory pandemonium of ideas into something orderly and definable. Combined with his two successors Plato and Aristotle, this triad would come to determine the course of philosophy for the ancient and medieval worlds. As such, Kreeft devotes many pages to them, especially Plato and Aristotle, who actually wrote out their ideas (Socrates famously dismissed the need for writing in the Phaedrus).

With the groundwork laid, it becomes evident how every philosopher and philosophical school, even those in the Muslim world, are in fact responding to Plato or Aristotle. Stoicism, Neoplatonism, Epicureanism, Cynicism, and skepticism, as well as Scholasticism and nominalism, all spring from the same source.

* * *

Much of this will be familiar terrain for those of us who take an interest in philosophy. Not only do these thinkers serve as worthy models of philosophical discipline (who doesn’t want to have the fortitude of the Stoics, the logic of the Scholastics, or the moderation of the Epicureans?), they are also quite readable. Kreeft goes to great lengths to show how most of these philosophers are not only deep thinkers but also eloquent writers—though one would probably do well to consult Peter Kreeft’s Summa of the Summa if he feels inspired to take on St. Thomas Aquinas.

Even for those well-versed in the two giants of Christian philosophy and theology, St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, there are still a few lesser-known philosophers whom Kreeft brings to the fore. While John Scotus Eriugena’s focus on God’s unity and Al-Farabi’s emphasis on the philosophical method and language did not immediately make a noticeable impact on the thinking of their time—both were quickly overshadowed by other philosophers—their ideas reemerged centuries later in the writings of thinkers like Leibniz and Wittgenstein.

After the Middle Ages, philosophy took a dramatic turn with Rene Descartes, who set it on a new, mostly secular foundation. Although revolutionary in many ways, he nevertheless maintained an unbroken thread with his immediate and distant predecessors—he and those who followed in his wake were still Socrates’ children.

Descartes’s radical skepticism (captured in his famous statement, “I think, therefore I am”) opened up endless questions in epistemology (the study of knowledge as well as logic and perception), which in turn gave rise to the scientific method.

As with Plato and Aristotle, subsequent philosophers and philosophical schools mainly defined themselves by responding to Descartes. Empiricists like Hobbes, Locke, and Hume placed more emphasis on sensory inputs, while rationalists like Spinoza and Leibniz continued to explore what was known through reason alone. Meanwhile, Blaise Pascal, a genius in his own right, cast doubt on these queries altogether.

* * *

The arguments only became hopelessly convoluted and abstract with the post-Enlightenment German philosophers, starting with Immanuel Kant, who sought to reconcile rationalism and empiricism with complex theories of subjectivity.

This also happens to be where Kreeft does his most heroic and important work. He actually has read the works of these men—prefacing some of these chapters with the frustrated admission that he might not have caught everything—and so encapsulates these abstruse musings in clear concise chapters. He is even able to make the ideas of someone like Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel accessible. In fact, his chapter on Hegel is one of the best in the series.

In fact, this overview of Hegel, while enjoyable, also allows Kreeft to provide enough of a background to cover the 19th and 20th philosophers in the final volume of the series, since Hegel turned out to be “the touchstone, the end of the classical modern era in philosophy and the philosophy against which all subsequent philosophical schools define themselves.” Fortunately, unlike the German philosophers, many of philosophers of the past two centuries were fine writers who communicated their ideas at least somewhat clearly, like Søren Kierkegaard, Jean-Paul Sartre, John Stuart Mill, Bertrand Russell, and especially G.K. Chesterton. Others, like Jacques Derrida and Emmanuel Levinas, apparently didn’t believe in such conventions and simply tortured their readers. Kreeft even “praises” the former: “I must compliment Derrida for writing the most remarkably unreadable prose in the history of philosophy. If the Godfather became a deconstructionist, he’d make me an offer I couldn’t understand.”

Although many might conclude that this period of philosophy might have the least value since this was when philosophy became hyper-intellectualized and rendered unfit for anyone who was not a specialist, Kreeft redeems these thinkers—though he can’t resist condemning the British analytic philosophers for killing philosophy: “Analytic philosophy is a trial infection: just as deadly, but boring.”

As Kreeft shows, many of these philosophers speak to humanity’s current condition, even in a technology-saturated age and offer helpful arguments in reconciling or at least appreciating today’s paradoxes. It’s not all pretentious word games and existentialist dread (OK, maybe a little bit). Much of it is a vindication of ancient ideas that trace all the way back to, yes, Socrates. As such, Kreeft ends his list with the group of Thomists who espouse the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, himself a champion of the methodology of Socrates and advocate of common sense to philosophical discussion.

* * *

Overall, besides giving an equally intensive and extensive education on the world’s greatest philosophers, Socrates’ Children makes a persuasive case for the enduring relevance and usefulness of philosophy. Yes, it’s often difficult conceptualizing these ideas, understanding all the logic, and working through the implications, but this work is surprisingly satisfying and enormously rewarding.

In many ways, Kreeft effectively saves the study of philosophy with this work. He brings even the average person up to speed and keeps the conversation going. And if enough people read the series, and those readers go on to take Kreeft’s advice and continue their education by reading further and learning from these philosophers’ own words, I’d go so far as to say that Kreeft has every right to take additional credit for saving Western civilization as well.