It’s getting harder and harder to have a movie that isn’t caught up in the culture wars. Franchises like the MCU, Lord of the Rings, Star Wars sagas, and Disney’s Pixar animations, which once united a broad spectrum of viewers, now get yelled at by both sides, either for not being progressive enough on the one hand or being too “woke” on the other. Instead, our entertainment is increasingly focusing on appealing to smaller and smaller subgroups of people who share similar values.

As film critic Alissa Wilkinson put it: “As pop culture continues to splinter into niches and micro audiences (thanks in part to technological advances), it frequently caters to our individual and identity-group preferences, siloing art rather than creating art that might be watched by a range of audience members.”

Similar issues face parts of the faith-based film industry. Angel Studios, best known for the Jesus-focused TV series The Chosen and the anti–sex trafficking film Sound of Freedom, has long tried to make films that bridge the gap between mainstream and faith-based audiences. The trouble is, the faith-based space is fracturing right now between a reliable audience of Christian moms who want family-friendly inspirational dramas like I Can Only Imagine, and a growing male audience that wants more overtly political and edgy content like the Daily Wire’s Am I Racist? and producer Mark Joseph’s Reagan.

Angel Studios has long tried to unify these disparate audiences, with mixed results. Its attempts to gain the support of the politically motivated audience that made Sound of Freedom a massive hit, such as partnering with the Daily Wire to release Sound of Hope and marketing Bonhoeffer with allusions to conservative podcaster-author Eric Metaxas’ biography of the Lutheran pastor and martyr, have resulted in highly publicized blowback but without the financial and critical return they were looking for. But avoiding controversy altogether, with films like Cabrini, hasn’t helped box office either.

Now Angel is betting big that its fortunes, literally, are about to change with their new movie Homestead, directed by Ben Smallbone (Johnny Cash: The Redemption of an American Icon). Described by the studio as “The Last of Us meets Lost in Space meets Seal Team” and based on the Black Autumn book series, Homestead follows multiple families in the aftermath of a nuclear attack in Los Angeles. They try to weather a collapsing society hunkered down on the wealthy Ross family’s estate, called “Homestead,” led by the family patriarch, Ian Ross (Neal McDonough).

The studio has high hopes for this franchise. The film functions as a backdoor pilot for both a scripted TV series launching the day of the film’s release and a reality show under the same “Homestead” banner. They describe it as perfectly suited to appeal to mainstream audiences while amplifying light in this dark time:

In plenty of post-apocalyptic entertainment—a genre that’s gained lots of popularity over recent years—the characters tend to showcase the worst in human nature. The danger and disaster they face often break them, causing these characters to degenerate as the story unfolds. Homestead is a refreshing break from this pattern; viewers will be inspired by the Homestead characters’ positive development.

Unfortunately, the movie doesn’t end up “amplifying light” or bridging the gap between audiences. In fact, it sows much of the division that is the problem in the culture it’s trying to address.

The idea of a story about post–societal breakdown America that focuses on families is a great one. In the real world, families—particularly rich, connected families—would be the communities most likely to have relative stability in such a situation. So it’s a more realistic twist on the genre, opening up fun narrative possibilities. And the significant overlap between religious Americans, family-oriented folks, those who see themselves as “conservative, and those who are part of the modern “homesteading” movement—i.e., those who tend to have an affinity for rugged individualism—means that the concept has real potential for audience crossover. because the genre itself already has mainstream appeal.

But the film goes downhill pretty quickly, with badly underwritten characters. Homestead introduces us to family after family in rapid succession, all of whom escape a collapsing society by resorting to the Ross compound. But all these families fit into a very shallow archetype without much development: mom cooking, teenage girl on phone with her boyfriend and yelling at her brother who’s playing video games, family patriarch leading and wife following, etc. Why have a bunch of individual families if there’s going to be no variation among them?

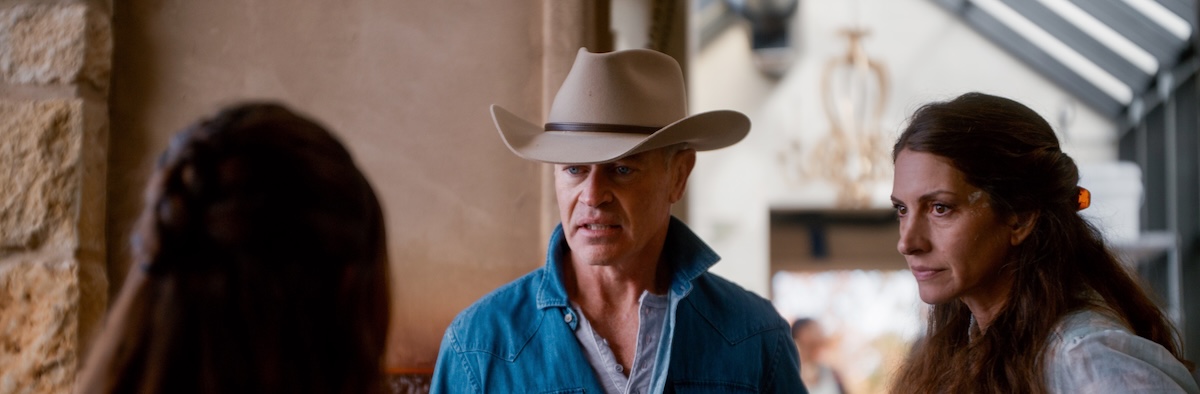

Eventually, many of the individual characters grow to be slightly more distinct, but remain paper thin. Jeff Eriksson (Bailey Chase) is the tough-as-nails former Green Beret. Malcolm McNulty is a naive hippy type who is erratic without his meds. Ian Ross is the man in charge of the compound trying to keep everyone safe while being challenged on all sides. His daughter, Clair (Olivia Sanabia), is a wholesome homeschooled farm girl. and Abe Eriksson (Tyler Lofton), Jeff’s son, is the angsty teenage boy with the heart of gold (so obviously, they develop a sweet, paint-by-numbers romance). The wives and mothers of the families are mostly exchangeable wise and nurturing figures.

The main conflict is the clash of ideologies as to how they should run the Homestead once they’re there. Jeff Eriksson wants to run it under martial law as an autocratic military compound that shoots trespassers on sight. Ian’s wife, Jenna Ross (Dawn Olivieri), wants to welcome everyone who asks. Ian wants to balance these concerns, even as he’s accused of being soft by one side or heartless and fearful by another.

This is where Homestead starts to pick up. It’s an engrossing conflict. And it forms the heart of the appeal of the post-apocalyptic genre, particularly for a conservative male audience. Because the world is dangerous and no one is coming to save you, life involves hard choices that will often be painful, and where the right thing isn’t always clear. So your choices really matter and your ability to step up and make those choices makes you heroic. And that’s true whether you’re making a risky, compassionate choice or a cruel-seeming one.

But the movie undercuts this compelling friction by eventually revealing that there’s really only one right choice: to reject violence and welcome people. When a character hits a man who’s attacking a woman, he’s chastised and treated like the problem character. When characters make the call to shoot someone, they end up regretting it. When characters turn people away from joining them in the compound, they’re always wrong.

This creates a film that is humorously at war with itself. The main conflict is people debating complex moral issues and yet we are told that they aren’t complex after all. We have lots of cool men with really cool guns, but the only time someone gets shot and killed, the people involved get shamed and end up admitting they were wrong. The movie insists on being largely family-friendly as well, which means that even as the narrative erupts in a final big shootout—not a single person dies.

This is the problem with trying to appeal to both traditional faith-based Christian audiences/the rising Christian male audience and mainstream viewers. Traditional faith-based viewers are looking for comfort-food content. They want stories where parents and children are reconciled (I Can Only Imagine), the sports game is won (Facing the Giants, American Underdog), and the sick person is miraculously healed (Miracles from Heaven, Breakthrough). If there are good guys and bad guys, they want it to be clear who’s right and wrong (God’s Not Dead), and for the good guys to win.

These moviegoers also suffer from an allergy to moral complexity. In faith-based movies, moral issues and the bad guys are always clear. The atheists in political fights with Christians in the God’s Not Dead franchise are always pure evil and power-hungry, even though that’s an unfair, broad-brush caricature. And the Best Christmas Pageant Ever church ladies trying to keep the Herdmans out of the church pageant are portrayed as motivated purely by pharisaical judgmentalism—even though the Herdmans are bullies who force their way into the pageant by threatening to hurt the other kids. So come on, the church ladies have a point.

This oversimplification is particularly evident as Homestead’s story nears its end. (Warning: spoilers!) As a result of the shootout, Ian Ross winds up in a coma. When he wakes up, Jenna tells him that she used the turmoil to let everyone in. But it all worked out because everyone there was able to use their skills to fix all the problems they’ve been having with energy and food, so now there are no food shortages!

In her words: “I let our friends in. All of them. I let them all in. Lucky for us my God is bigger than math. I bet it all. Our safety, your life, on faith. Loaves and fishes. There’s life … and then there’s life worth living.”

Trying to combine this kind of moral simplicity and a post-apocalyptic hellscape is a fool’s errand that will likely please neither your faith-based nor your mainstream audience. Fans of the gritty genre will find the sanitized moralizing boring and insulting. Fans of faith-based films won’t find the gritty and violent trappings compelling.

But there’s deeper problems with this storytelling than an inability to satisfy your mixed audience: Homestead insists that moral complexity doesn’t really exist, which encourages hating your neighbor. Why? If moral issues aren’t complicated, then people who disagree with you can’t have any good reasons for that disagreement. They must just be bad people.

Seeing our neighbors as evil is a growing problem in the United States. A recent study by Johns Hopkins Universityfound that nearly half of Americans view the other side of the political aisle as “downright evil.” This has real-life consequences. As Zeynep Tufekci noted in the New York Times, a recent Reuters investigation found that, since 2021, America has had “the biggest and most sustained increase in U.S. political violence since the 1970s.

Hollywood has long encouraged caricatured depictions of people the filmmakers disagree with, such as Christians and conservatives. It’s particularly easy to draw a line between their “Eat the Rich” genre of movies and the shocking levels of support for the UnitedHealthcare CEO killer. The issue isn’t that faith-based movies are worse than Hollywood productions. It’s that they’re claiming to be “better” but are doing the same thing.

Consider this: If Jenna Ross really did let everyone into her compound, she would be forced to make some really hard choices. Yes, bringing more people in might actually increase resources: more people means more innovation (which is why overpopulation alarmists like Thomas Malthus were wrong that more people would lead to mass starvation). But it’s helpful to keep in mind that the kind of creative output and economic prosperity enjoyed especially in the West happened because of the Industrial Revolution, which spurred the growth of private property and free markets. Would Jenna Ross divide her estate up into private property? Would that properties then have to be purchased? Collectively owned property tends to lead to stagnation (e.g., the tragedy of the commons), and state subsidies like Universal Basic Income (giving everyone cash with no strings attached) make people less likely to work and result in a decline in community engagement, the caring for others (let the government do it!), and self-improvement. So how would Jenna get everyone to work if they just expected to be given something from the more productive? Would she make them all serfs at gunpoint?

We need more stories that help us build empathy and moral maturity by taking the difficulties and complexities of such topics seriously. We need more films and TV series we can all enjoy together, that cross our divided communities, so we can create a common culture and share common experiences. And we need those stories to be of good quality so that we want to watch them and don’t just feel an obligation to help some Christian filmmakers. Homestead wants to be a refuge in a time of social decay, but it ends up merely adding to the moral chaos.