Dr. Lee Edwards, historian of the American conservative movement and self-professed “admirer of the Acton Institute and its important work,” passed away last week at the age of 92.

Edwards was more than a scholar of the conservative movement: He was a pivotal person in it. He was present in Sharon, Connecticut, in 1960 for the writing of the Sharon Statement and helped to found Young Americans for Freedom.

In The Liberal Imagination, published in 1950, Lionel Trilling wrote: “The conservative impulse and the reactionary impulse do not, with some isolated and some ecclesiastical exceptions, express themselves in ideas but only in action or in irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas.” This might be better than John Stuart Mill’s calling conservatives “the stupid party,” but not by much.

Three years after Trilling’s book, Russell Kirk responded with the groundbreaking and well-received The Conservative Mind, an intellectual history of conservative thought beginning with the great British statesman Edmund Burke. Emulating Walter Bagehot, Kirk used the phrase “reflective conservatism” to describe Burke’s call for using the “moral imagination” to preserve civilization against ideologues who sought a radical remaking of society.

Edwards was just such a “reflective conservative.” He also was a devout Catholic who earned his Ph.D. in politics from the Catholic University of America. His Catholic faith shaped his defense of liberty and commitment to the inviolable dignity of the human person.

This commitment to human dignity was the lens through which he viewed, and chronicled as an author or editor of 25 books, human events. Witnessing the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 inspired his lifelong opposition to communism, including his role as founding chairman of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation.

There were other important lessons Edwards learned from studying communism and the American political and intellectual leaders who opposed it. One was the necessity of a strong U.S. military as a deterrence, which he traced to Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan. Edwards was director of communications for Goldwater’s 1964 campaign. According to Edwards, Goldwater was not a libertarian but a fusionist who “successfully melded the conservative and libertarian ideas.”

Another lesson Edwards drew from his historical studies was the necessity of American leadership, which he sought to apply after the unilateral annexation of Crimea by Russia in 2014: “If you talk to people in Poland or Hungary or the Baltics, they are very concerned about Putin and how he will use his power, because he is an authoritarian, so they look to the United States to exert leadership.”

So, does this mean Edwards was a “neoconservative” in the way that term is pejoratively used today? No. For one thing, he was raised in a deeply anti-communist, conservative family. He grew up fully aware of reality and had no need to be “mugged” by it.

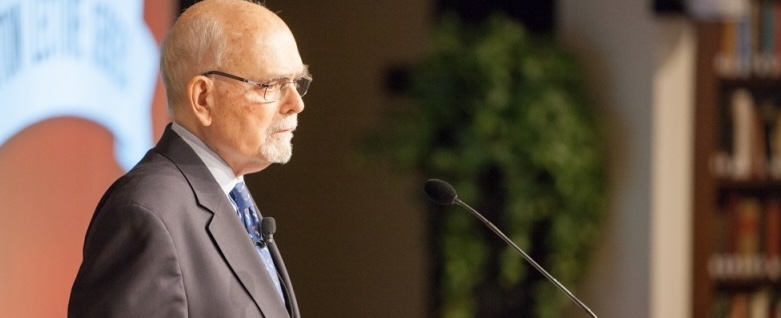

Neither did he count himself a libertarian. Edwards was a fusionist who rejected ideology precisely because he was conservative. “Ideology,” he told an audience at the Acton Institute in 2017, “is the enemy. I’m a Russell Kirk traditionalist, and I reject ideology because it is rigid and because it is monolithic and because it is arrogant and thinks it has all the answers.”

Ideologues do not engage in debate, are uninterested in the pursuit of truth, and treat politics as war that demands total victory in every contest. Edwards, on the other hand, believed that “we should be willing to listen to the other side. We should be willing to try to persuade them to take our position and not to demand that they do so and to reject them if they don’t agree with us.”

Compromise, Edwards knew, is not the same as surrender. Like Kirk, he recognized that, in the pursuit of liberty, the prudent and reflective conservative must be willing “to take the 70% now and come back for the other 30% later.”

Edwards recognized that the same problems plaguing American political discourse generally were responsible for shattering the fusion he had helped to bring about. He singled out the demand for instant analysis by social media and the 24-hour news cycle. In his view, this prevented deep exploration of ideas and thereby limited the potential to score real policy wins by passing important legislation.

Edwards also lamented the decline in civility, erudition, and magnanimity in American political discourse. Ideas have consequences, and it turns out that how you promote those ideas also has cultural and policy consequences.

I met Lee Edwards only once, when I interviewed him in 2010 for a radio program about his newly published book William F. Buckley Jr.: The Maker of a Movement. We had a pleasant, hour-long conversation about the American conservative movement. Lee emphasized the eclectic mix of talented thinkers and writers Buckley gathered at National Review in the 1950s and ’60s, as well as Buckley’s formative role in uniting a fragmented right into a conservative movement.

In addition to all these accomplishments, and perhaps most important of all, Lee Edwards will be remembered as a kind, gentle, and humble man. To the last, he continued to encourage conservative-minded Americans and libertarians to think about their “fundamental commonalities” rather than what separates them. In the quest for a free and virtuous society, I think that is great advice from a great conservative.