On February 16, 2024, Alexei Navalny died under mysterious circumstances in the remote Siberian penal colony to which he was moved in late 2023. Founder and leader of the Anti- Corruption Foundation, Navalny was a long-time dissident and one of the most vocal critics of Putin’s regime over the past two decades, so his suspicious death was no surprise to anyone remotely acquainted with contemporary Russian politics. Indeed, the BBC article that reported Navalny’s death devoted most of the space to listing other recent unnatural deaths of individuals who had seemed to pose any threat to Putin’s power.

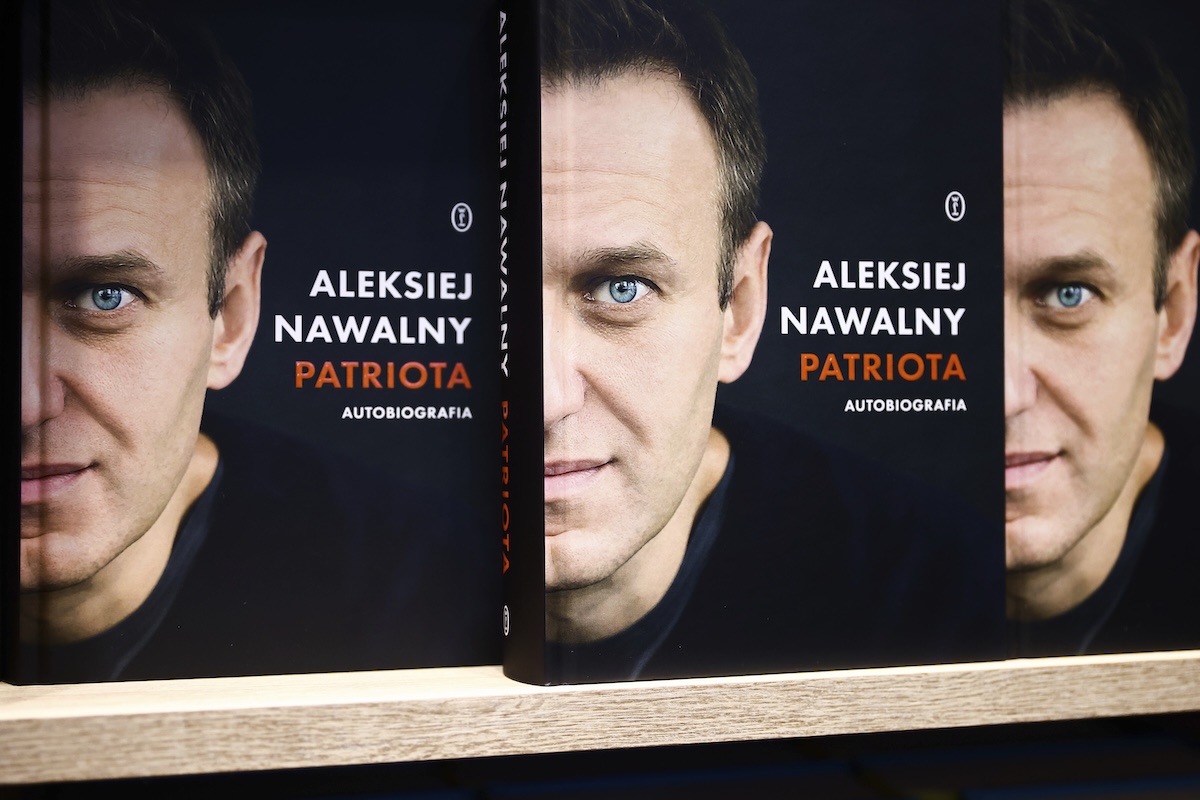

Except Navalny got the final word after all, speaking from beyond the grave through his powerful, moving, and at times unexpectedly funny new memoir, Patriot, published this fall. Its existence testifies that, to the end, Navalny lived up to his reputation as a true Russian dissident—someone whose pen is mightier than his sword.

In his recent history of Soviet dissidents from the 1960s to the collapse of the USSR, historian Benjamin Nathans remarks on the genuine patriotism these dissidents displayed time and time again as they denounced the abuses of the Communist Party and the country’s rulers. A particular focus for every dissident had been the pursuit of freedom of speech—the right to criticize the regime and its leaders, and to do so in elegant and sparkling prose, as befits denizens of the land of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Bulgakov. Inevitably, though, harsh repercussions followed, leading to the popular toast of Soviet dissidents, which Nathans adopted as his own book’s title—“To the success of our hopeless cause.”

Navalny’s memoir now shows the continued hopelessness of that cause in Putin’s Russia. Sure, the Soviet Union doesn’t exist anymore. And yet, with Vladimir Putin at the helm now for nearly a quarter century, old KGB thugs and oligarchs connected to them rule the country, suppressing freedom of speech and access to any sort of communication both within and outside. Elections are rigged in favor of Putin’s United Russia party, and all remotely successful challengers find themselves stymied by legal trouble or assassination attempts. Furthermore, while the gulags technically don’t exist anymore, brutal penal colonies, fit for housing dissidents, are still very much around. In addition, there are show trials and secret executions of those deemed a threat. In the process, human dignity in Russia is valued as much—or, rather, as little—as it was in the days of Stalin.

Such is the tale Navalny tells of his career as political lawyer and activist, a career that largely overlapped with Putin’s rule. In many ways, though Navalny is just a few years older than me and was just a teenager when the Soviet Union collapsed, his story eerily resembles those of the dissidents of the USSR of yore. Like them, he prioritized education and the learned life, had a way with words, possessed a patriotism combined with a desire to effect change, and had a conviction that any repercussions he would incur were worth the goal.

The book opens with the first—failed—attempt at poisoning Navalny in August 2020. Convalescing in Germany, Navalny made the decision at that time to begin writing his memoirs. Moving back in time from that moment, he reminisces about his childhood and adolescence in the Soviet Union. What was it like to grow up in Communist Russia? As I remember from my own childhood, reality was what the state told you it was.

One early example Navalny recalls of the state-run deception machine has to do with the Chernobyl explosion in 1986. Navalny had relatives near Chernobyl who were relocated afterward, but not before the Soviet authorities had first sent all residents of the region to dig up the fields, filled with radioactive dust and residue, and plant a new crop of potatoes there—all to put up a charade for the world that all was well. The message was clear: Keeping up a good face for the state was more important than protecting the lives of citizens. Navalny also tells a humorous story of how his grandmother, who had fish drying in the attic when the evacuation orders came, did not want to waste them and mailed the delicacies to Navalny’s dad in Moscow: “It looked very appetizing, and my father decided he would enjoy it with a beer. Only when my mother kicked up a fuss did he agree to fetch a radiation meter. The fish was so radioactive it was as if an atom bomb had been dropped on it. My mother took it into the forest and buried it there.”

Perestroika and glasnost at the tail end of the USSR made free speech—and criticism of the regime—possible for a brief while. Navalny absorbed these lessons while noting the continued state corruption that was keeping regular citizens in poverty. He reports one telling anecdote that reflects the absurdity of this time:

Someone buying pies is surprised by their appearance and asks the vendor, “Excuse me, but why are your pies square?”

“Perestroika.”

“Right, but why aren’t they cooked.”

“Acceleration.”

“And why has someone taken a bite out of them?”

“State accreditation.”

This background is important. Navalny got to experience the USSR’s final years and swirling-around-the-drain absurdities. And yet his formative years came during a time of hope amid the collapse—a time when it seemed easy to accept at least some of the promises of perestroika and glasnost and wonder if something new was afoot. At least black limousines were no longer making their rounds at night, whisking dissidents off to the gulags.

Entering the political realm in the early 2000s as a young lawyer, right as Putin was first elected to power, Navalny retained his hope, even as he saw the powerlessness of opposition parties like the (highly incompetent) Yabloko party. Navalny was a member of Yabloko for a time and tried to push the party in a direction he thought would lead it to greater electoral success. For his efforts, he was expelled. “The pretext was my ‘nationalism.’”

Yabloko’s main trouble was inertia rather than corruption. Everywhere else, though, Navalny found that corruption reigned supreme in post-Communist Russia, just as it had since the days of Lenin. To his shame, Navalny admits he, too, had bought into the necessity of, for instance, bribing a professor to receive a passing grade on a university exam. But the experience left him feeling disgusted with himself as much as the system, and wondering over time: What might Russia be like today if the corruption and thieving that has been baked into the system for so long were to be eliminated?

Average Russian citizens might be financially better off, for one. In Navalny’s view, Putin had stolen 20 years from Russia—two decades that could have turned Russia into a prosperous country. Instead, those years served only to further line the pockets of the already ultra-rich.

This realization became the foundation of Navalny’s anti-corruption work and his general platform in speaking out against Putin and the oligarchs backing him. So what did this political activity look like for Navalny?

The gist of my political strategy is that I am not afraid of people and am open to dialogue with everyone. I can talk to the right, and they will listen to me. I can talk to the left, and they too will listen. I can also talk to democrats, because I am one myself. A serious political leader cannot simply decide to turn his back on a huge number of his fellow citizens because he personally dislikes their views.

He goes on to conclude that “fair and free elections” are essential.

If you can get them, that is. Alas, “In Russia, power doesn’t change because of elections,” as Navalny first observed in 2011. In fact, the situation only grew worse: not only did blatant vote rigging continue in elections—parliamentary and presidential—but the persecution of any who opposed Putin also intensified. So what is a serious dissident to do without access to the press and without the opportunity to line up large venues for political gatherings and debates? In the old days, of course, the two solutions were samizdat (domestic underground self-publishing) and tamizdat(publishing dissident literature abroad and then importing it into Russia for underground distribution). But the times were changing, and Navalny realized early that a better option was available to him. Welcome to the internet, of course.

It is humorous to consider that, unlike China, whose leaders promptly banned Google and heavily policed the internet from its inception, Putin and other Russian leaders didn’t foresee any serious threat from the digital realm. True old-school Russians to the core, they respected only the printed word and saw no potential for a challenge from the electronic medium. Their mistake.

Meanwhile, Navalny accumulated millions of followers for his blog. Then, when the authorities caught up and shut it down, he began using Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, becoming the ultimate dissident influencer. Producing weekly documentaries on YouTube, in particular, Navalny reached millions with prominent stories of government corruption. No wonder Putin saw his best chance in the poisoning attempt of 2020—except it failed.

Still, when Navalny returned from Germany to Russia in January 2021, he was immediately arrested at the airport and never regained freedom. And so the final portion of the memoir takes the more traditional form of a prison diary, even as Navalny himself fears becoming a cliché in writing in this overused genre. But even the form of the diary conveys the worsening of conditions. Initially able to access writing materials and time for this work, he is moved repeatedly to increasingly more secure—and abusive—prisons, until ending up at a remote penal colony above the Arctic Circle for the final month and a half of his life. In the process, we see the diary entries dwindle from longer daily reflections and bona fide essays to shorter observations, memories, frustrated descriptions of show trials, and a report of a hunger strike to which he had to resort to be allowed medical care. And then there is the unpaid labor he was required to perform in prison. For trying to unionize the prisoners, he was transferred to another, more secure prison.

The gulags of old are dead. Long live the new gulags. Perhaps not much has changed after all since the days of Solzhenitsyn.

While I was repeatedly reminded of the dissidents of yesteryear, Navalny’s disposition throughout this memoir displays a key difference: While the old dissidents were toasting “to the success of our hopeless cause,” Navalny repeatedly affirms his conviction that Putin’s reign of terror will not last forever. Russia’s freedom will become a reality someday. “I don’t know how my life is going to pan out,” he reflects at one point. But he explains why continues to fight: He loves his country and wants its good.

But while Navalny didn’t know what was coming as he penned the last diary entry published in this book, on December 31, 2023, the rest of us know of the untimely end he met soon after. So what does it all mean now?

Atop Navalny’s Russian YouTube video-blog as of this writing is a black banner with the title “Navalny Killed” and below is the latest video—a message from his widow, Yulia Navalnaya, together with several other speakers. Titled “Against Putin and Against the War,” the video presents a familiar case: Putin is a dictator, a murderer, and a war criminal who must be removed from power immediately, and the Russian war in Ukraine must end.

Will this happen? I hope so, but I lack any confidence to believe it will anytime soon. A century after Lenin’s death, Russia’s present only looks more like its Soviet past.