September 11 is not usually portrayed in cinema, perhaps as a sign of respect for the most shocking event in recent history. Perhaps it’s also because we do not know how to deal with terror. But if it’s a surprise that Hollywood has largely steered clear of the subject, a greater surprise still is that the only one of America’s celebrated directors to make a movie about the attacks is Oliver Stone, our most committed left-wing artist.

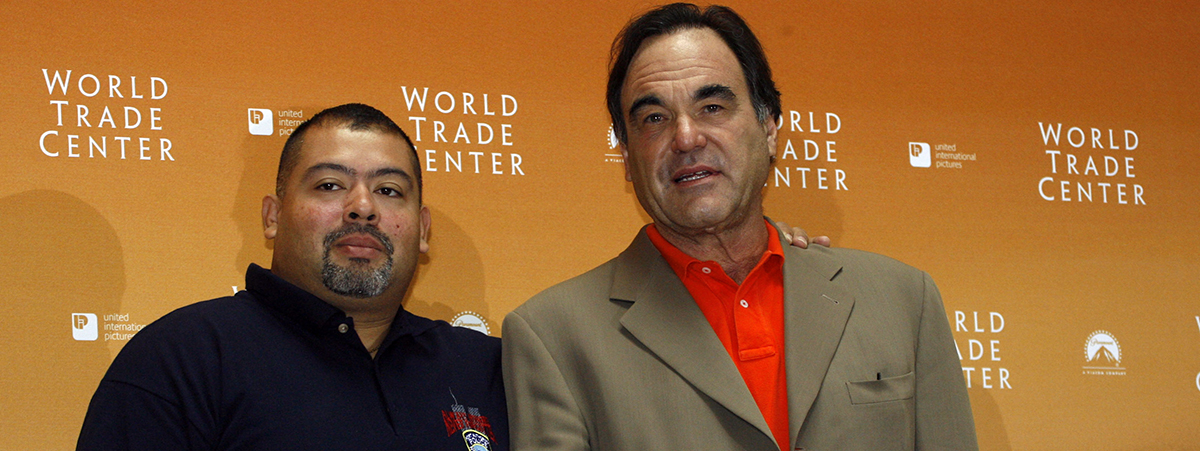

Most surprising of all, his 2006 movie, World Trade Center, is a wonderful portrait of America at her best. It’s a story of blue collar patriotism, moral virtue, and sacrifice, proof that a terror attack cannot break national character. Moreover, it’s a true story following Port Authority policemen. Nicolas Cage plays our protagonist, Sgt. John McLoughlin, who assembles volunteers to respond to news of the North Tower being hit by the first plane. Among those who answer the call are Antonio Rodrigues (Armando Riesco), Will Jimeno (Michael Peña), and Dominick Pezzulo (Jay Hernandez), and later Officer Christopher Amoroso (Jon Bernthal).

Since we all know the story in advance—without even realizing it, we learned the events of 9/11 almost live—what’s at stake instead is the stories of the first responders, the people involved in the catastrophe who acted, as well as their families. The policemen at the center of the story, McLoughlin and Jimeno, are married, and the movie cuts from them, at Ground Zero, to their wives Donna and Allison, played by Maria Bello and Maggie Gyllenhaal, who are desperately trying to learn what’s happening.

World Trade Center was something of a success back in 2006, making around $160 million worldwide, but it wasn’t celebrated, even though it showed a worthy picture of America to audiences both home and abroad. There is an injustice in this fact and a missed opportunity. The anniversary of 9/11 is a good opportunity to remember the movie and, without spoiling the action, finally to realize its importance and the public spirit that gave birth to it. At the same time, since 9/11 sometimes seems forgotten in the rush of crazy new events, the movie can help us remember and thus finally fulfill its task as a work of art.

I’d like to focus on those scenes of families separated by service and suffering, because there we get to the core of the movie. Stone is at his best in filming middle-class America, and for once suburbia looks morally impressive. Mothers taking care of their families in a moment of crisis, people praying in church, and in general the organization of the community for mutual help—everything we somehow take for granted in the ordinary course of events turns out to be the source of the moral courage of the men who head into danger as first responders. As in all cases where self-interest and moral principle diverge, we see character revealed, and though we do not wish for suffering, we cannot help noticing that it is a condition of noble displays.

Dramatizing nobility, always a difficult thing when the subject is delicate, usually concerning true stories, is especially thorny in such a situation, because it may seem not only easy but almost a matter of good manners or even moral duty to become sentimental. This is a difficulty that affects not only producers and artists but also critics and the audience. Everywhere the question is, What interpretation must we put upon the events and the actions? Another way of looking at that difficulty is to ask how we understand what is best in us or how we act at our best.

So far as Stone is concerned, I think people should conclude on the strength of this movie that he is much more patriotic than his reputation suggests and that much of the agony depicted in his movies or indeed the strange things in his career follow from the tenderness he feels for the America he grew up in, its promise of decency and respect to all Americans. Accordingly, World Trade Center is not a partisan movie in any sense. Even the sentimentality contributes to a search for understanding of American character. The obvious difficulty Stone faces in his other works is that the American way of life is now so far removed from the major public institutions, whether politics or media. Only in World Trade Center does he get to show the solid foundation from which American freedom is forged. Moreover, he cannot be accused of flattery in his patriotism because not only is he famously critical of what he sees as injustice but he is also trying to restore confidence by his depiction of America, not to please arrogance. He knows that America needed reassuring in the years immediately following 9/11.

What reassures people also says much about them. Americans looked to first responders like the men depicted in World Trade Center and seen onscreen in the movie’s coda, returning us to reality, so to speak, because we believe that ordinary men can become heroes in extraordinary circumstances, even though our concern for safety and property makes us avoid those circumstances most of the time. It seems we as a society both shy away from heroism and embrace it passionately.

The movie hints rather delicately at the cause of the acts of heroism it displays: shame. When the men volunteer to try to save whomever they might meet down at the World Trade Center, they have no clear idea of what happened or how dangerous it is. A kind of love for fellow Americans, although in a way they’re merely strangers, moves them to act; perhaps there is something Christian in that motive, too. But in the chaos of events, it is the feeling they have for each other that moves them—they could not trust each other in dangerous moments, as their profession requires, without also feeling that they must act or else be dishonored. That is an intensity of love rarely reached and yet somehow it is implied in all our care for each other.

This is the highest theme in the movie, and it is the emotional throughline that gives unity to the work of art and most clearly reveals its intention. There is a mix of sorrow and relief in knowing that we believe in something greater than ourselves in order to help each other, and that these men proved on that day what we all hold to be true, that we think of heroism as sacrificial, defensive of everything we hold precious even as we feel defensive about it and do not wish it to be tarnished. Perhaps this is why events that transpired in a terrifying way on television are also in another sense a national secret.

Oliver Stone’s movie, and also this essay, is a case of saying what should go without saying. That’s somehow correlative to the problem of commemoration, that we wish never to forget something that is painful to remember. That’s the purpose of art, after all, and both by its beauty and by what it makes us think about, it offers a kind of compensation for suffering. So give World Trade Center a chance.