In John Adams’ estimation, the American Revolution began with an argument in a back room in Boston. “Who of your profession will undertake to paint a Debate or an Argument?” the former president asked of the artist John Trumbull in a letter in 1817. Adams had just read the news that Trumbull would be completing a series of historical paintings chronicling the major events of the Revolutionary War, a project that had spanned most of Trumbull’s adult life. The series would include a number of key points in the fight for independence, from the Battle at Bunker Hill to the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown. The scenes, however, would not all be military engagements. At the center of the collection would be a portrait celebrating the submission of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, a scene in which John Adams himself would play a prominent role.

The former president was not happy. The story of the Revolution was not found in singular, picturesque moments. The truth for Adams was that it had been a far messier and unwieldy struggle than that. And it had hardly begun in 1776. Adams assured Trumbull that it had begun with an argument over writs of assistance between James Otis and Jeremiah Gridley back in 1761. “Here the Revolution commenced,” Adams lectured Trumbull in his letter. “Then and there, the Child was born.”

Adams certainly had a profound intellectual point. But Adams had never been mistaken for a man of the people. The task of capturing the essence of the Revolution in the imagination of generations of Americans to follow would not fall to Adams. Instead, it would be the life’s work of John Trumbull. As historian Richard Brookhiser demonstrates in his accessible, insightful, and enjoyable biography Glorious Lessons: John Trumbull, Painter of the American Revolution, we are all the benefactors of Trumbull’s project, which contains far more nuance than Adams gave it credit for.

John Trumbull was born in colonial Connecticut in 1756. Graphic art was not a high priority in this Calvinist society, deeply suspicious of its emotional power and ability to seduce the worldly-hearted. Religious paintings were the tools of papists, not the Bible-devoted Congregationalists of New England. Trumbull’s father, the last colonial governor and first state governor of Connecticut, tried for years to dissuade his youngest child from pursuing painting. His pleas were to no effect. John Trumbull had been in love with art since his earliest memories.

The young Trumbull attended Harvard, at his father’s insistence, and studied math and “perspective”—the skills for map-making. He graduated in 1773 and returned home to Connecticut, destined for some public service career like his father and older brothers, but the Revolution intervened.

John Trumbull would serve admirably in the Continental Army, at various points working directly under General George Washington and General Horatio Gates. His skills and bravery in mapping enemy positions made him useful to the Patriots’ effort. After the war, he worked for a time in diplomacy, serving as John Jay’s personal secretary during the negotiations of Jay’s Treaty in 1794, which averted another war with Great Britain. But art was never far from Trumbull’s mind. In the later years of the Revolution, he had traveled to Great Britain to study with American expatriate Benjamin West, the most famous historical painter of the day and preferred artist of King George III. Following his studies, Trumbull was commissioned to paint a number of prominent Americans, including a notable full portrait of President Washington for New York City’s City Hall.

Portraiture, however, would not be the defining work of Trumbull’s life. Instead, he would spend the remaining decades of his life painting the major events of the Revolution. The project had initially been the vision of his teacher Benjamin West. But West had quickly found that it would not be practical for him to try and paint the events from the losing side given that none of his British countrymen would want to sit for his paintings. Trumbull, on the other hand, was deeply patriotic, a true believer in the virtues of the Revolution. He also had firsthand experience of some of the conflict’s most important battlefields, like Bunker Hill, and the first coalition fighting with the French in Providence, Rhode Island.

Trumbull intuitively understood what the Revolution had been all about. He expressed this knowledge in a 1789 letter to his friend Thomas Jefferson. The events of the American Revolution, he wrote, had been “the noblest series of actions which have ever presented themselves in the history of man,” teeming with benefit for future generations, “such glorious lessons of their rights, and of the spirit which they should assert and support them, and even to transmit to their descendants.”

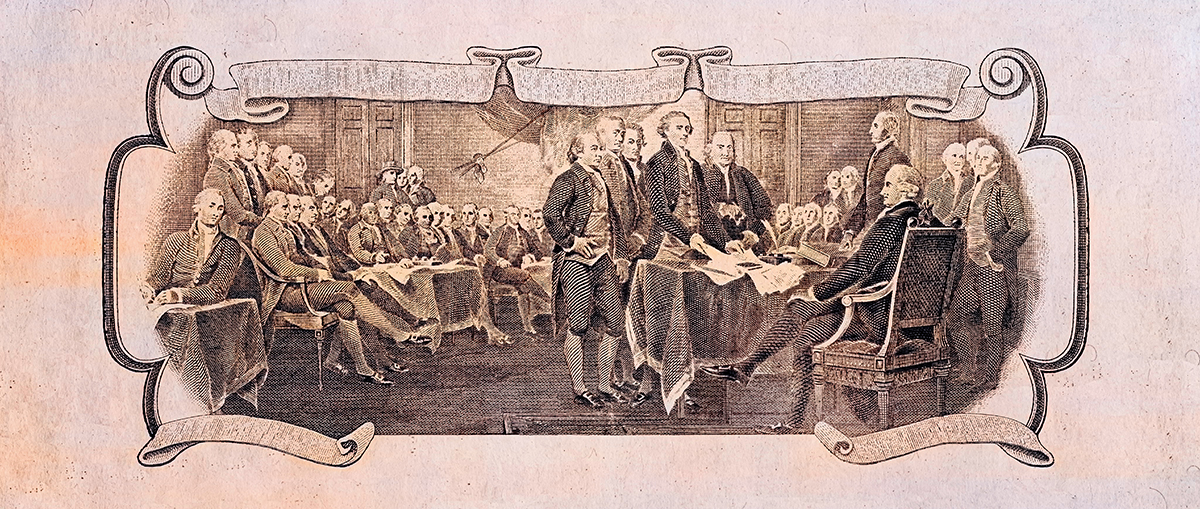

As Trumbull had originally conceived it, his series of paintings would focus on battles. Each one centered on a significant death, much like West’s famous The Death of General Wolfe. It was Thomas Jefferson who encouraged the artist to include the Declaration of Independence as one of his scenes. Jefferson even went so far as to draw a sketch of the room in the Philadelphia State House where he and the committee had presented their drafted document (a sketch that mistakenly included two doorways into the meeting room rather than one).

Trumbull’s grand project was completed over multiple decades, and the artist’s skills visibly declined over the period, a fact that some of his contemporaries noted. What never failed him, however, was his masterful composition and passion for enshrining the highest virtues of the revolutionary generation. Four of Trumbull’s large scenes, The Declaration of Independence, The Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga, The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, and The Resignation of General Washington, would be hung in the new Capitol Rotunda in the decade of national jubilance following the War of 1812. But Brookhiser focuses the largest portion of the art criticism in Glorious Lessons on the fuller gallery that Trumbull curated at Yale University. Trumbull had been a Harvard man, but the newer college in his home state provided the artist with the full control over the collection that he desired. He was even able to assist in designing the new building to house his art. Brookhiser first encountered this collection, he recounts in the book’s opening, as an undergraduate student. In the last section of the book, the author spends multiple chapters going painting by painting to analyze how the piece was conceived and completed and why it’s important to the story of the American Revolution.

Part biography, part early American history primer, Glorious Lessons does a commendable job of intertwining the history of the American Revolution and the first 70 years of American history into the story of John Trumbull. Whether you’re a student of the early United States or in need of a refresher on the key events and people of period, Brookhiser’s historical narrative is both nimble and insightful. Trumbull was either present for or closely connected to many of the significant events of the era, but even when Trumbull was not present for a major occurrence like Washington’s resignation, Brookhiser finds thoughtful ways to navigate to the important details.

The greatest strength of Glorious Lessons, however, is Brookhiser’s eye for the enduring significance and nuance of Trumbull’s work. In an era in which so many of the artist’s subjects and contemporaries—from Washington to Jefferson—have faced the fiery criticism of a generation no longer persuaded of the virtue and achievement of the American Revolution, Trumbull’s work stands as a needed counterbalance. Brookhiser peels back the veneer of 19th-century romanticism to reveal the deeper messages in Trumbull’s works. For one, the victories of the Revolutionary War were hard fought and costly. Trumbull had witnessed firsthand the deadly toll of war and he brought those emotions to his canvas. Speaking of her experience viewing Trumbull’s The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, First Lady Abigail Adams wrote, “My whole frame contracted, my blood shivered, and I felt a faintness at my heart.”

Despite his sensitivity to the dearness of the American sacrifice, Trumbull did not vilify the enemy. Brookhiser highlights a number of instances where the artist’s work portrays the British magnanimously, a considerable feat of humility for a man who endured British musket fire at Quaker Hill. Yet Trumbull pays minimal attention to the involvement of Black Americans and Native Americans in the war. (His most important work on Native Americans, though, came from his sketches of Alexander McGillivray and the Creek Muscogee delegation at the signing of the Treaty of New York.) The artist was not immune to the social and cultural prejudices of his time, Brookhiser points out, but neither was he blind to the significant roles of racial minorities in the human history of the era either.

Loyalists, however, do not fare so well in Trumbull’s work. Their experience—the experience of as many as a third of American colonists, according to John Adams’ estimate—is completely absent from Trumbull’s depictions of the period. His was an unabashedly patriotic account. While he called himself a historical painter, he certainly had a point of view. He also felt justified in taking some artistic liberties with the scenes he constructed, transplanting some of his subjects across space and time on more than one occasion to complete his compositions. His most profound stories, though, are those that took place far from the battlefield in government assembly halls. Brookhiser contends that The Declaration of Independence and The Resignation of George Washington are the most important works of Trumbull’s catalog. “The Declaration expresses the ideal,” Brookhiser writes. “The Resignation shows it being made real.”

John Trumbull is buried beneath the gallery of his art (a fact that still intrigues Yale students today). Though we are now two centuries removed from his time, his message, Brookhiser convincingly contends, is as salient as ever. At its core, Glorious Lessons tells the story of the price and benefits of self-government. Trumbull and his generation plead through these canvases that Americans not resent their heritage of individual rights, nor the high character required to exercise them rightly in a civil society. Brookhiser’s volume is a thoughtful, elegantly written, and beautifully illustrated (Trumbull’s most important works are reproduced here in full color) reminder that the Revolution was not a once-and-for-all accomplishment in the past, but a continuing practice now in need of our care and attention.