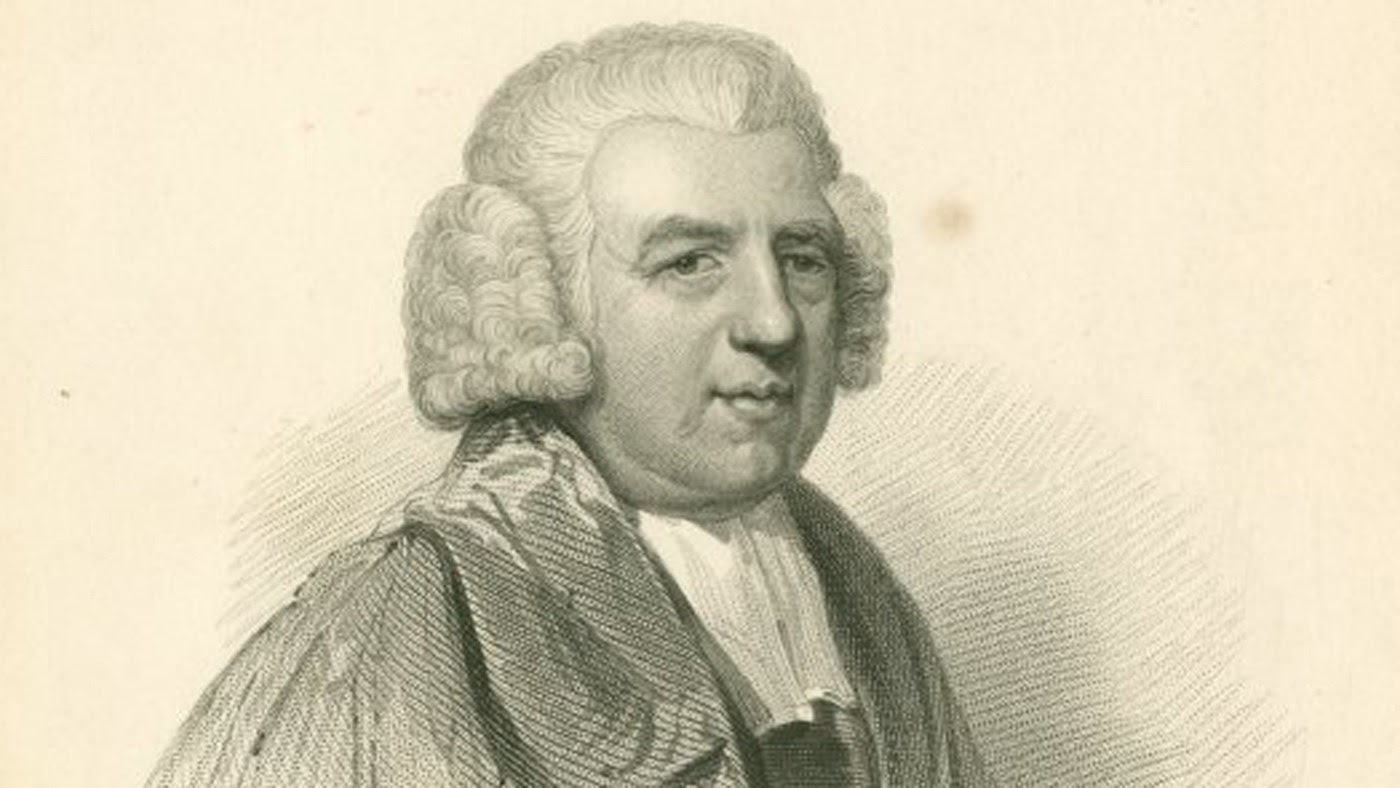

John Newton (1725–1807) is a pivotal figure in the English evangelical revival or awakening. His is an early example of a settled evangelical ministry in the second half of the 18th century, involving pastoral work, hymn-writing, and even mentoring the likes of a William Wilberforce. Yet Newton began as an unconverted, rugged sailor, known for mocking authority and trading in slaves. His conversion to Christ, however, initiated a slow but steady transformation. As theepitaph for his gravestone reads, which he himself composed:

John Newton … once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in Africa was by the rich mercy of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ preserved, restored, pardoned and appointed to preach the faith he had long laboured to destroy.

John Newton was born on July 24, 1725, to John and Elizabeth. His mother was devout, his father regularly absent at sea. His mother died before his seventh birthday; his father remarried quickly. Newton himself was destined for a career at sea, and there were numerous ships and voyages, a press gang, and even a desertion. At age 21, he entered the employment of Amos Clow and thus began his direct involvement with the slave trade, through which he prospered. Newton’s father, who remained concerned for his son’s welfare, sent a ship to the African coast to seek him out. Newton, attracted by a made-up story of a legacy and the not-made-up story of his love for Polly Catlett (his eventual wife), joined the Greyhound and headed back across the Atlantic.

On board, extraordinarily but by divine providence, Newton picked up a copy of Thomas á Kempis’s Christian classic, The Imitation of Christ. He had never encountered anything like it, and he began to wonder if the Christian claims might be true. On March 10, 1748, Newton was awakened in his cabin by a storm, the ship’s rotten timbers broken by the waves and floodwater swirling into his cabin. One man was swept overboard, and the ship was badly damaged. As he recorded in his Authentic Narrative, published in 1765, this was when he began to pray and read the scriptures. Newton viewed his spiritual encounter on the Greyhound as his conversion experience, “a day much to be remembered by me,” “on that day the Lord sent from on high and delivered me out of the deep waters.” Yet he knew that he understood little and experienced many setbacks and backslidings. It was over the next seven years that his Christian life and convictions would be shaped.

It is perhaps hard for us to understand why Newton continued to captain slave-trading ships after his “conversion”—first the Brownlow (as second-in-command), then the Duke of Argyle, and two voyages on the African. Indeed, in his Authentic Narrative, there are no reflections on the evils of the slave trade; that conviction would come later. He married Polly in 1750 and corresponded with her on his last trip on the African, telling her that he was praying for her and reading the scriptures. On this trip, he also met a Christian trader (not in slaves), Alexander Clunie, who mentored Newton in the faith. He then became acquainted with George Whitefield, first in London and then Liverpool, describing himself as a Methodist for the first time. (“Methodist” was used at this time to describe all evangelicals, rather than to describe a separate denomination.) As Methodists taught, sanctification—a growth in holiness and Christian maturity—is a process,and for the hardened sailor and slave trader Newton, it took some time.

Newton felt increasingly drawn to ordained ministry but was less sure about which denomination. He had some objections to the Church of England, but these softened under the influence of other ministers. The path, however, was not straightforward.

To gain ordination you needed a post, testimonials to character, and a willing bishop. The last of these was the most problematic for Newton. Initially he was refused ordination by the Bishop of Chester and then by the Archbishop of York.

What was the problem? Although Newton felt well disposed toward the Church of England, he also made it clear that he was not attached to any particular denomination and expressed doubts about both infant baptism and the apparent assumption of salvation in the burial service. He was also concerned about a regnant opposition to evangelicals within the Church.

He received several offers to accept appointment in independent churches and was close to accepting one from a Presbyterian church, when an evangelical aristocrat, the Earl of Dartmouth, intervened. He had read Newton’s autobiographical Authentic Narrative and was impressed. He controlled the appointment to a post in Olney in Buckinghamshire and offered it to Newton. Newton was again rebuffed by the Bishop of Lincoln and the Archbishop of York, but then Dartmouth pleaded directly with the Bishop of Lincoln, who agreed to interview Newton—who proceeded to express his doubts about the liturgy. Finally, on April 29, 1764, Newton was ordained, after a seven-year saga. He declared that his “only hope is in the name of Jesus.” The this-world hero of the story, however, is Lord Dartmouth, preventing the bishops from washing their hands of Newton altogether.

Newton was in post in Olney from 1764 to 1779. Evangelicals had a gift for revitalizing moribund parish ministries. Newton was known by his parishioners; he walked the streets, not in clerical clothing, but in his sailor’s jacket. He visitedthem. He supported and cared for the poor and needy, wrote letters, ensured the supply of Bibles where needed, and studied the scriptures himself. He preached twice on a Sunday, three other times in the week, and gave a lecture on Sunday evenings. He was not naturally a great preacher and was sometimes both unprepared and unguarded in what he said.

Central to Newton’s Olney ministry was his relationship with William Cowper (1731–1800). Cowper (pronounced “Cooper”) was one of the greatest English poets of the 18th century but who faced a long-term struggle with mental illness. His deep and lasting friendship with Newton produced the Olney Hymns. Cowper’s mental anguish was very deep and included time in an asylum. He came under the care of an evangelical household, the Unwins, and after her husband died, Mary Unwin and her two children, with Cowper as the lodger, moved into a property adjacent to Newton’s rectory in Olney. Newton reached out to his depressed visitor with Christian compassion and practical encouragement, and would sometimes be called to the Unwin home at 3 in the morning to calm Cowper. During one bout of serious mental despair that befell Cowper in 1773, Newton noted in his diaries that “My dear friend still walks in darkness. I can hardly conceive that anyone in a state of grace and favour with God can be in greater distress.”

Newton worked with Cowper to write hymns, culminating in the publication of the Olney Hymns (1779). This entailed a three-fold division, with 141 hymns on selected texts of scripture, 107 on progress and changes in the spiritual life, and 100 on various other subjects. Newton’s writing was characterised by simplicity, rhythm, and an ease of singing. Cowper was always the poet. Examples still sung today include Newton’s “How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds” and Cowper’s “Jesus Wherever Your People Meet” with its reminder that Christ is not confined by walls (the very release that Jesus offered to Cowper). And, of course, there is “Amazing Grace”—written for a service for New Year’s Day, January 1, 1773.

Olney, though, was not easy ministry, with numbers in church and at prayer meetings beginning to fall. After 15 years, fresh pastures beckoned. Newton’s ministry had become more widely known and appreciated, and an opportunity opened up for Newton to obtain a post in the City of London, the business and banking district, where an evangelical presence was weak. In 1779, he was appointed to the rectory of St. Mary, Woolnoth, a church that nestled in the shadow of the Bank of England. In his first sermon, he described the Bible as “the grand repository of the truths that it will be the business and the pleasure of my life to set before you.” Newton’s ministry attracted a growing number of hearers, and soon a gallery had to be built at the church to accommodate them.

When William Wilberforce was a boy, his aunt and uncle brought him to meet Newton at Olney. In late 1785, whenWilberforce was 26, he wrote to Newton requesting a secret meeting. Wilberforce himself was a converted and changed man but struggling with whether to remain in public life as a member of Parliament or to enter the ministry. Wilberforce was so anxious about being spotted, he twice walked round the square where Newton lived before knocking at the door. In early 1786, Newton wrote to Cowper about Wilberforce, saying that “I hope the Lord will make him a blessing, both as a Christian and a statesman.”

It was a turning point. Wilberforce became a regular Saturday visitor and Sunday congregant. Newton became a public campaigner for the abolitionist movement when, in 1787, he collaborated with Wilberforce and others in the formation of the Anti-Slavery Society and in January 1788 he published his highly influential pamphlet Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade, describing the horrors he had seen. In this Newton acknowledged his personal involvement and responsibility, and he repented. His personal experience put him in a strong position to campaign, which he did with Wilberforce for the next 19 years. Although he was perhaps late to the scene, both evangelical and wider public opinion was changing. Abolition of the slave trade succeeded in the year Newton died.

Unlike Wilberforce, Newton was not a politician or a statesman. But he was a pastor. Unlike Whitefield, he was not a great orator. But he spoke powerfully. Perhaps most important, Newton had a backstory, one that formed and shaped him in the campaign against the slave trade. He also exemplified the somewhat uneasy relationship betweenevangelicals and the Church of England—the former were committed to the established church but were as much at ease in an independent chapel. The preaching of the liberating gospel of Jesus Christ was what mattered most. This Newton knew, and in time proved a great model, mightily used by God.