A new school year has just begun, and students and their parents are faced once again with the high cost of higher education.

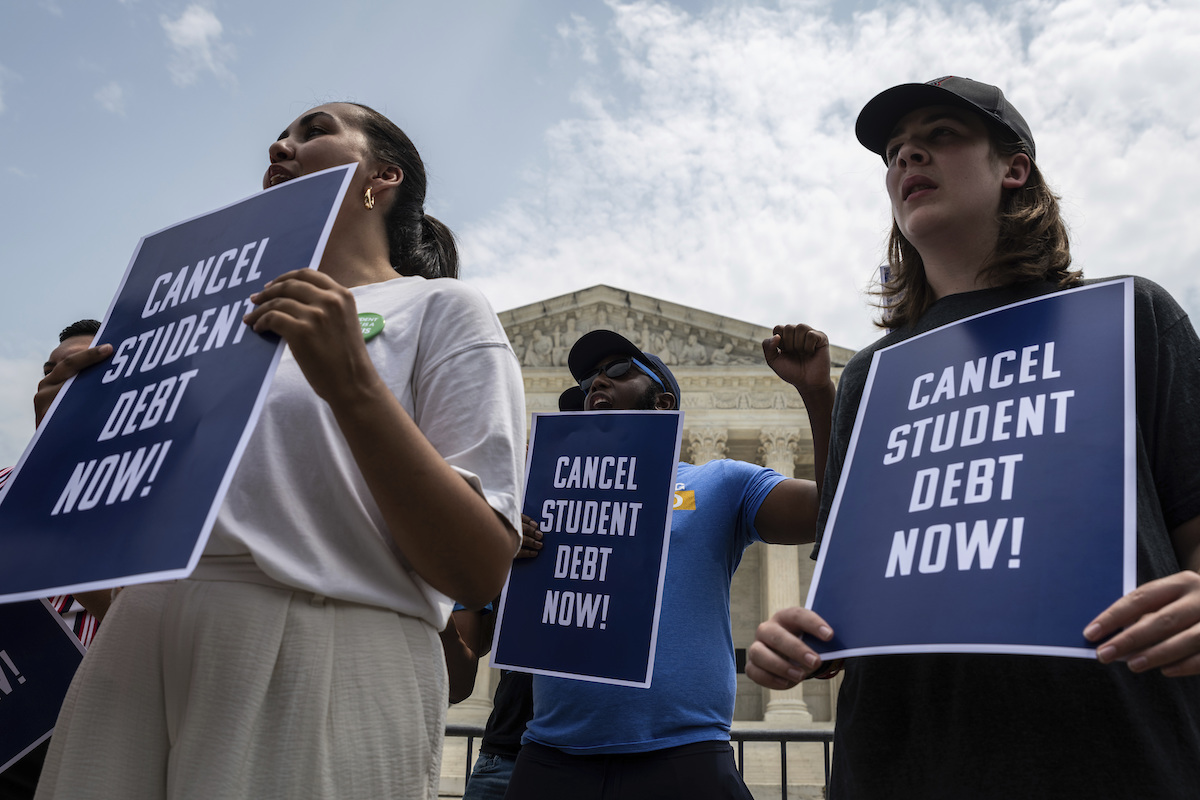

The Supreme Court ruled President Biden’s executive order on student loan forgiveness unconstitutional. Undeterred, the president has since expanded income-based repayment. Predictably, Democrats defended it and Republicans attacked it.

Meanwhile, many continue to struggle with student debt. Tuition has nearly tripled since the introduction of federal loans in the 1980s. Predicted earnings for graduates have diminished. For some majors, according to Forbes, bachelor’s degrees now underperform even an associate’s degree or just a high school diploma.

Christian theology, however, can cut through partisan debates on loan debt to the underlying moral issues through its teaching on the sin of usury.

Usury cannot be reduced to excessive interest. Doing so misses the spirit of traditional Christian concern with interest-bearing loans.

Historically defined as the charging of any interest, before the Protestant Reformation usury was generally forbidden by church authorities based on the compromised position of borrowers. The Scholastics recognized some payment beyond the principle to be justified, but the general ban on interest, despite a few exceptions, stifled financial progress. However, the prohibition was rooted in a genuine moral rationale.

In a time before bankruptcy protections, default on a loan could result in destitution, imprisonment, or slavery. Jesus even used debtors’ prison to represent hell, warning, “You will by no means get out of there till you have paid the last penny” (Matthew 5:26).

Elites consolidated wealth through lending to distressed borrowers. The Scriptures condemn those who “take usury and increase [and] have made profit from [their] neighbors by extortion” (Ezekiel 22:12). Saint Augustine described a “cruel usurer” as one “desiring to wring gain from other’s tears.”

Absent bankruptcy protections, lenders retain a contractual right to repayment even when investment isn’t profitable. We see this asymmetry in St. Gregory Nazianzen’s claim that a usurer “farm[s], not the land, but the necessity of the needy.” Lenders were not required to take pity on borrowers who couldn’t repay.

By contrast, modern bankruptcy laws limit exploitation, and healthy competition among lenders reduces interest rates. Yet subjugation through lending still affects some borrowers who lack bankruptcy protections: students.

Student loans may be provided by the Department of Education or private investors. The federal government guarantees repayment for private investors. As detailed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, backed by the state and exempt from many bankruptcy protections, lenders do not share the hardship of borrowers, incentivizing moral hazard.

According to Sallie Mae, “You don’t need a strong credit history to get federal student loans” and “You don’t need a cosigner.” Lending standards are practically nonexistent.

Between 100 and 150 billion dollars annually are lent to borrowers with no collateral or consideration of credit history or repayment prospects. The expected value of the education received is not considered. GPA requirements do not consider the difficulty of classes. The state compensates lenders for the uncertainty of borrower quality by making more difficult the delay of repayment and the discharge of student loans in bankruptcy.

According to the Department of Education, default will result in garnished wages, with the employer “withhold[ing] up to 15 percent.” Discharge is only possible if borrowers can’t “maintain a minimal standard of living … for a significant portion of the loan repayment period,” and they previously “made good faith efforts to repay.” Of those who do qualify for discharge, the adversary proceeding determines if borrowers must still repay a portion of the loan, possibly at a lower interest rate.

Over the past decade, borrowers with credit scores lower than 620 received about a third of all funds lent via federal student loans. Including all borrowers considered less than prime (credit score below 660), the number of borrowers falls between 40% and 50%. Under current institutional arrangements, lending to low-rated borrowers without regard to the expected value generated looks a lot like premodern usurious exploitation, an attempt “to wring gain from other’s tears,” as St. Augustine put it.

Biden’s most recent action might provide some relief to low-income borrowers, but it misses the real problem: the usurious structure of federal student loans crowding out alternate aid and career paths for low-income, high-risk students and swelling college costs for everyone. We need to do more than treat the symptom. We should start this new school year right by repenting of the cause and reforming the system that incentivizes the sin in the first place.