At the end of August, the Hong Kong government charged a Cantonese language group with “threatening national security.” The latter had posted online an essay, cast in the form of fiction, that emphasized the city’s loss of liberty.

Andrew (Lok-hang) Chan, who headed Societas Linguistica HongKongensis, explained that the group, which published the essay, was only related “to arts and literature” but nevertheless was “targeted by the national security police.” He closed the association in response.

Hong Kong’s brutal assault on human rights has disappeared from newspaper front pages, which is a victory for Chinese president Xi Jinping and Hong Kong chief executive John (Ka-chui) Lee, Beijing’s local gauleiter. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has effectively extinguished Hong Kong’s inherited British liberties.

After the territory’s return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1997, the Special Administrative Region enjoyed political autonomy that was supposed to last a half century. However, in June 2020, after years of increasing popular unrest, China imposed the expansive National Security Law (NSL), effectively outlawing criticism of the PRC. Since then, the Hong Kong government, now headed by Lee, has arrested more than 260 people under the NSL and prosecuted more than 3,000 people on charges under other statutes, most long after the targeted conduct.

The conclusion of the European Commission’s latest report on Hong Kong is grim:

2022 saw the continuing erosion of Hong Kong’s high degree of autonomy and of rights and freedoms that were meant to be protected until at least 2047. The year was also marked by the far-reaching implementation of the NSL. Trials of pro-democracy activists and politicians continued to intensify. Many people were awaiting trial, including 47 pro-democracy activists who participated in a primary election, members of the now-disbanded Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, media tycoon Jimmy Lai and many others. Many of them have been held in custody since January 2021, in some cases in solitary confinement. The colonial-era sedition law was repeatedly used in national security cases. In July, the United Nations Human Rights Committee in its fourth periodic review under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in Hong Kong called for the repealing of both the NSL and the sedition law.

The low point this year has been the mass trial of the 47, a Who’s Who of city democrats. Their alleged crime was to organize a popular vote to choose candidates for the upcoming Legislative Council election. The PRC’s local enforcers retrospectively declared the defendants’ action to be subversive and a threat to national security. The proceedings began in February, a dramatic example of how the law is used to punish even the mildest dissent, with any opposition to Chinese rule considered to constitute a threat. The outcome of the case seems preordained.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam, whose maladroit administration triggered mass demonstrations, enjoyed watching her pro-democracy tormentors suffer but appeared to be more cheerleader than persecutor. John Lee, who took over earlier this year, is playing a more active role as chief executive than did his predecessor and is apparently determined to wreak vengeance on anyone who ever criticized Beijing. Among his targets are booksellers and journalists. In April, his government even arrested a Hong Kong student who condemned the CCP on social media while studying in Japan. Such are the “national security” threats that cause the mighty Chinese state to tremble.

Passage of the NSL encouraged what one official described as an “alarming” exodus from Hong Kong. Tens of thousands of people relocated, many young professionals. Among them were parents determined to protect their children from communist indoctrination. Previous reeducation plans were derided as brainwashing and thwarted by popular protests, which have become impossible today.

Despite a recent population uptick, Hong Kong’s rulers are concerned about the prospects of the city-state’s global pretensions. Government propagandists downplay the role of the NSL, instead emphasizing high housing prices and long working hours as the reasons for the failure to attract more young workers. Lee has “launched a campaign to convince the world that despite Covid-19 and a brutal security crackdown, the Chinese territory is not only open for business but remains Asia’s premier financial center.”

That will be difficult given the ongoing assault on civil and political liberty. Particularly noteworthy is Lee’s campaign against people who sought asylum abroad. For instance, the pro-democracy party Demosisto, co-founded by Nathan Law, disbanded when the NSL was enacted. Law and seven other Demosisto activists fled Hong Kong before it became an open-air prison. In July, Lee’s government arrested four people, former Demosisto members all, “suspected of using companies, social media and mobile applications to receive funds that they then provided to the people overseas,” as well as making “seditious” social media posts.

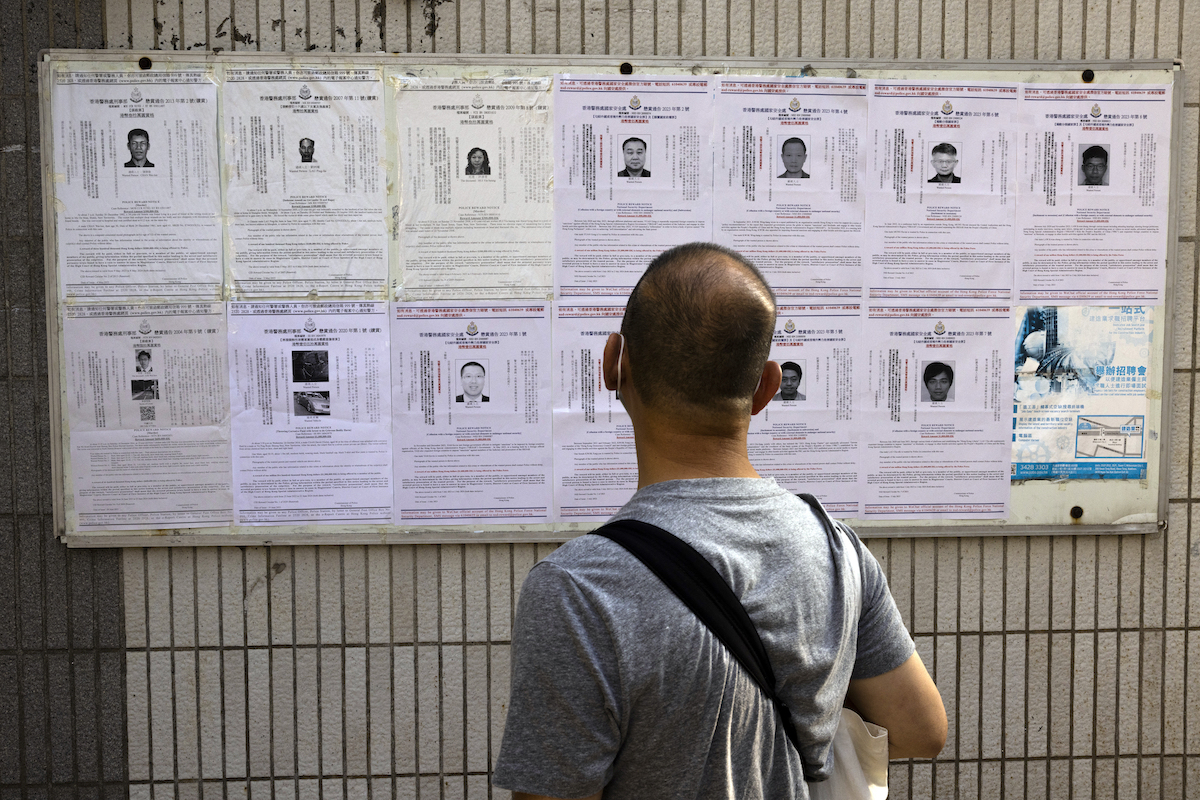

Yet Lee’s main target remains those beyond his geographic reach. The authorities have offered a bounty of $128,000 for information leading to their prosecution, an award available to family and friends, Lee emphasized. As in Les Misérables, the prosecutors promise to be unrelenting: “The only way to end their destiny of being an abscondee who will be pursued for life is to surrender.”

Lee’s enforcers are also targeting family members, most recently detaining Law’s sister-in-law: “She is suspected of assisting persons wanted by police to continue to commit acts and engage in activities that endanger national security,” said one local official. In this way, Hong Kong is openly mimicking the PRC’s unrelenting persecution of other dissidents, such as Uyghurs fleeing Xinjiang, pursuing them even when granted sanctuary abroad.

In fact, Cantonese promoter Andrew Chan, noted above, is also living abroad. Five policemen raided his father’s home, warning that Chan would “become the ninth wanted person if he does not take down the [fictional essay] article.” Nor are foreigners exempt. At least one American citizen has been charged under the NSL. In August, Danish artist Jens Galschiøt, creator of the “Pillar of Shame” sculpture at the University of Hong Kong, previously seized by the police, inquired whether an arrest warrant had been prepared against him, as reported in China. Hong Kong’s security head, Chris Tang, refused to answer but complained that “it is a common modus operandi of those seeking to endanger national security to engage in such acts and activities under the pretexts of ‘peaceful advocacy,’ ‘artistic creations’ and so forth.”

At least Liberty appeared to win a modest victory last month when a court refused the city’s request to order internet platforms such as Google to ban the song “Glory to Hong Kong,” the opposition’s unofficial anthem. However, the government has appealed, urging the court to treat Lee’s dictates as binding: “Where it is the assessment of the executive authorities that a proposed measure is necessary or may be effective or have utility, the Court should accord due weight and deference to such assessment and grant the injunction unless the Court is satisfied that it shall have no effect.”

In mid-August, another court overturned the conviction of seven activists for having organized an illegal protest. Although also welcome, the ruling was technical, regarding the elements of the offense, and had no practical effect. The defendants already had served their sentences and been convicted of participating in the same event.

In any case, such modest victories will be overwhelmed by new prosecutions under the NSL. Hong Kong now looks like any other Chinese city, in which civil and political liberties have become unknown ideals. Unfortunately, Hong Kong’s absence from the headlines reflects lack of attention, not of repression.