Rep. Tom Tancredo (R-Colo.) summarized what happened to George W. Bush’s 2001 anti-poverty “faith-based” initiative this way: It started out “with a certain merit, and you hope to God, literally, that you’re doing the right thing. … It’s amended, you know you had some part in passing it, and you now wish to God you hadn’t. … Soon you’re running out the door of the Capitol asking, ‘What have I done?’”

A literal running out of the White House signaled the end of compassionate conservatism as a Bush priority. On September 11, 2001, departing faith-based-office head John DiIulio and his second-in-command, David Kuo, were having their last White House breakfast together. Kuo in Tempting Faith describes the scene: “We heard voices from the stairwell yelling, ‘Get out! Everyone get out.’ [The two of us] were like Laurel and Hardy. John is short and very large. I am very tall and relatively skinny. John and I looked at each other and ran. … John was still toting the garment bag he had carried to breakfast.”

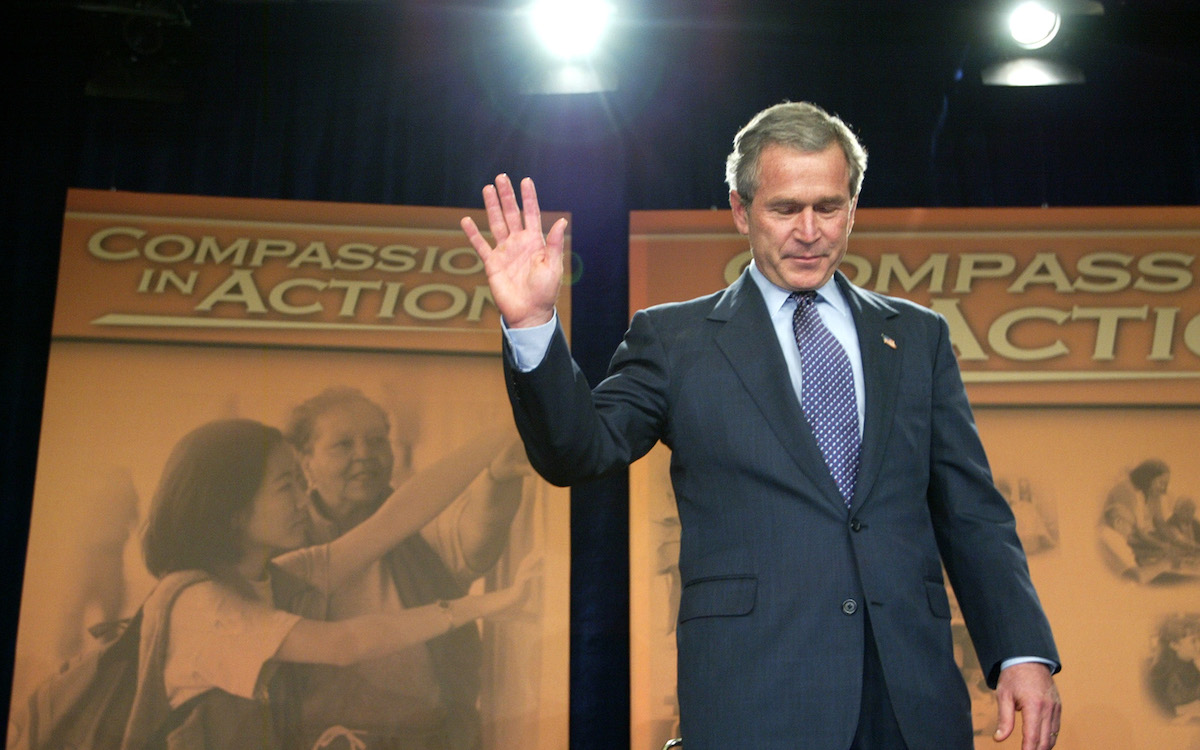

The White House was not hit, but on 9/11 George W. Bush moved from being a domestic-policy-oriented president to a war president. War and compassion don’t go well together. War is hell. War is also expensive. Bush, viewing the war on terror as his presidency’s defining issue, maintained Democratic support for it by accepting budget-busting increases in conventional domestic spending. Kuo stayed on into 2003 and received clear orders from a senior leader regarding legislation to advance poverty-fighting: “Forget about the f—ing CARE Act.”

Conservatives who equated compassionate conservatism with big government now had all the evidence they needed to call the doctrine a left-wing Trojan horse. The Cato Institute’s David Boaz in 2003 said the Bush administration’s approach “betrays true conservatism.” That was true about the centralizing emphasis that remained. Bureaucratic organizations adept at pushing paper and lobbying officials continued to rule. The idea of helping little guys remained, but the big way to help them (purportedly) was to provide instruction on how to apply for grants. That flipped compassionate conservatism on its head: instead of fighting bureaucracy, it built more bureaucracy.

Not all was lost. The Bush administration did promulgate executive orders that temporarily removed some discrimination against religious groups. The only clear success was international, through PEPFAR—the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. PEPFAR helped to fund grassroots groups, often religious in nature, that in many nations were major providers of medical services. Counting HIV-free births, PEPFAR probably saved 25 million lives.

President Bush continued to use the phrase “compassionate conservatism,” but Bush speechwriter David Frum in 2003 described it as “less like a philosophy than a marketing slogan.” Several scholarly books pointed out the difference between words and deeds. The best, Of Little Faith: The Politics of George W. Bush’s Faith-Based Initiatives (2004), offered the perspective of Christian college professors Amy E. Black, Douglas L. Koopman, and David K. Ryden. They pointed out that tax reduction and educational testing expansion (which proved of questionable benefit) were more important to the White House than direct poverty-fighting.

The Bush administration domestically said no to poverty-fighting tax credits and also minimized use of a semi-decentralizing mechanism—vouchers. As Stanley Carlson-Thies reviewed the eight Bush years in a 2009 issue of the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, vouchers could have led to diverse rather than standardized services, but most federal funding remained direct: “officials select one or a small number of providers, and any religious activities have to be kept separate.” For example, mentoring programs for prisoners “count on volunteers to pass on life wisdom and encouraging words,” but an hour of wisdom and encouragement could not include any mention of God.

My own sense is that the national compassionate conservatism rollout from 1995 to 2001 came too soon: yes, it gained a toehold, but the toe was gnarled and the nail ingrown. In a thoughtful scholarly article, “The Tragedy of Compassionate Conservatism” (Journal of American Studies, 2010), British professor Bruce Pilbeam said the phrase “compassionate conservatism” was mostly dead “thanks to its association with an administration that lost popularity in its second term even among conservatives.” He concluded, though, that the concept at local levels will have an “enduring legacy.” I agree.

I’ll close out this Religion & Liberty Online series with three notes from the year 2006, by which time both the Bush war on poverty and the initiative that replaced it, the war in Iraq, were bogged down.

One is about the Acton Institute, which in 2006 received applications for 10 awards from 247 neighborhood organizations that offered help to needy individuals. Most of these groups accepted no government money and did not spend their time and scant funds applying for government grants or attending workshops on how to apply for grants. They were hands-on, and they used the hands of many volunteers.

As World magazine editor-in-chief, I sent reporters to visit the 15 finalists. Their reports reminded me of what President John F. Kennedy said in 1963, in the then-divided city of Berlin, when he described the armchair pessimists of his time: “There are some who say that communism is the wave of the future. Let them come to Berlin.” Yes, compassionate conservatism as a Washington-centered initiative was dead, but in some local areas, ideals were still toppling idols. Let the pessimists come to those programs.

My second item from 2006 is the viewpoint of Bill Schambra, who at that time directed programs at Milwaukee’s Bradley Foundation and paid attention to grassroots efforts. He told listeners at American University, “If we only know how to look, if we only have eyes to see, within America’s local-income neighborhoods there are still—in spite of the contempt and neglect of the social service experts—neighborhood leaders who are working every day to solve the problems of their own communities.”

Schambra said their groups

are largely unheralded and massively underfunded, certainly by government but even by the private charitable sector. After all, they usually occupy abandoned storefronts in the most forbidding neighborhoods. They have stains on their ceiling tiles and duct tape on their industrial carpeting. They have no credentialed staff, and certainly no professional fund-raisers or slick promotional brochures. Furthermore, more often than not they are moved by a deep and compelling religious faith. They are convinced that human problems can’t be solved by social and psychological rehabilitation alone, but call instead for fundamental, spiritual transformation.

Schambra witnessed the work of

inner city volunteers who were themselves once trapped in the problems they are now helping others to overcome, in gratitude for God’s mercy, and in answer to God’s call. For them, crucifixion and resurrection are not just inspiring religious metaphors. They are lived, daily experiences—all-too-accurate descriptions of the depths of brokenness and despair they have faced, followed by the faint, hopeful glimmer of redemption.

I agree with Pilbeam and Schambra. I recently checked old notes and memories and realized I’ve visited organizations created to help those who are poor, homeless, uneducated, or abandoned in 153 cities and towns. Regardless of what people do or do not do in Washington, there’s a whole lot of helping going on.

The third voice from 2006 is David Kuo’s in his book, Tempting Faith. He was only 38 that year but was bravely blowing the whistle on the Bush administration’s lack of success: Kuo faced a cancer diagnosis, didn’t have a political future, and wanted to warn others not to make an idol of politics. Here’s how he concluded some instant messaging we did as his book came out:

D: $200 million has gone to the RNC [Republican National Committee] alone this year—almost all of it from small dollar donors, good men and women (probably Christian) who are wanting to do just the right thing

D: but what is it buying us? and are the Christians out there among the candidates really any different than the non-Christians in how they behave?

D: what if we made our enemies our friends by loving them so much that they had to wonder about this guy named Jesus

D: and we could say to them that the Good News of Jesus is that he rose from the dead and that those who follow him can one day do the same and that he can give life and give it in full here on earth?

D: how crazy

D: how nutty

D: how very cool a thing to try

D: I am a poor, poor, poor pilgrim—I stink at following Jesus—but marvin, it is my heart’s desire and everything I’ve written and said and hope for is about advancing jesus and I think my story is instructive because it is honest and people can learn off of my dime and because maybe my discoveries—painful discoveries—can be helpful.

David lived longer than doctors had predicted. He made it to April 5, 2013. That’s when he died of brain cancer, 10 years ago, five days after Easter.