Growing up in Yemen, a conservative branch of Islam was very popular in my household, school, and mosque. Freedom of religion was a myth frowned upon. It was thought that Islam is the right religion that will take us to Paradise, and the rest of humanity is, alas, going to hell unless they accept our narrow, stringent version of Islam. As a young kid I accepted that proposition, for I knew of no better alternatives. Even more, I was devoted to that branch of Islam, aspiring to attract other Muslims to my way of thinking.

However, at age 19 I was awarded a scholarship to pursue my college education in the United States. My first impression of the U.S. was its pluralism, where multiple faith traditions coexist peacefully. In Yemen we do not have any religious traditions besides Islam. Even so, sects within Islam compete against each other, fueling an ongoing civil war there, which is primarily fought over hard ideological lines and unfinished business that harks back to the precarious unification of the country in 1990.

After living for seven years in the United States, I realize that freedom of religion is not taken for granted here because certain religious traditions and a rising so-called neo-integralism would like to forcibly impose their own ideas through the law. Regardless of the means of enforcement, religion should always be embraced solely according to conscience. If history is any guide, we know that when religion muddles with government, the results are messy. As George Washington stated:

Religious controversies are always productive of more acrimony and irreconcilable hatreds than those which spring from any other cause. Of all the animosities which have existed among mankind, those which are caused by the difference of sentiments in religion appear to be the most inveterate and distressing, and ought most to be depreciated.

Later, Thomas Jefferson would concur in a letter to American Baptists, commending a wall of separation between government and religion.

Building a case for freedom of religion can be done in multiple ways. It can be derived from logical argumentation or from the Holy Scriptures or from historical lessons. The style of persuasion depends on the audience. But since I am concerned with Islam, I will make my case from within the Islamic tradition and advance the proposition that freedom of religion is inherently good.

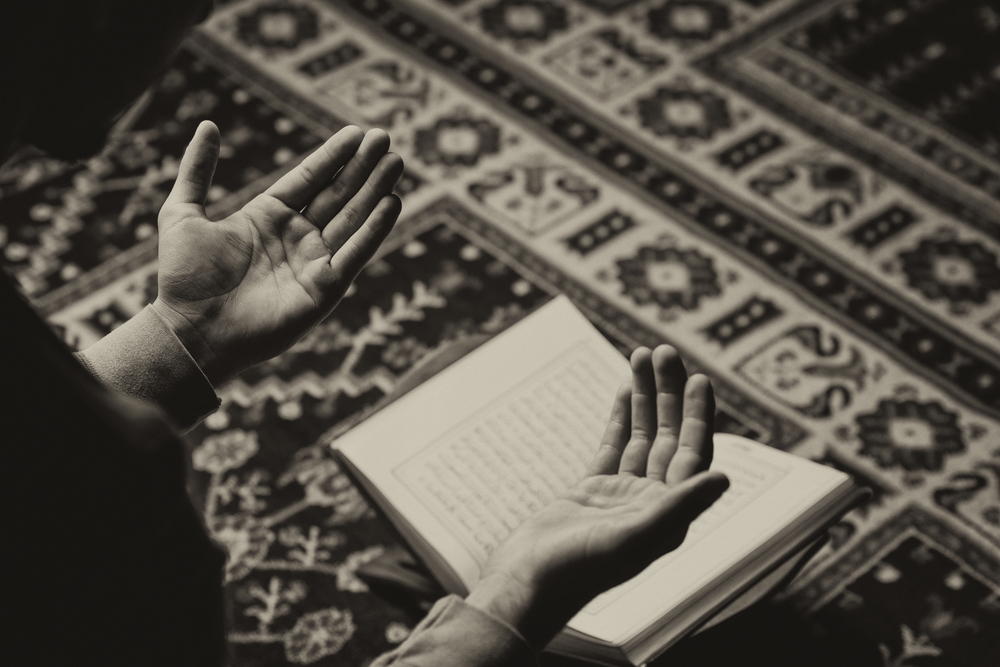

First, there is a famous verse in the Qur’an—“there shall be no compulsion in religion” (2:256)—that establishes the freedom for people to worship however they wish in this life. Humans have the agency to choose; the consequences of their actions may be judged in the hereafter, but that is a separate subject for a decidedly different essay. For now, however, the Islamic scriptures are unequivocally clear that neither manipulation nor coercion is a valid means of proselytizing.

Second, if religion should not be coerced, then we have to develop civil ways to engage each other in dialogue. Since humans are inherently fallible, having conversations with diverse people presents opportunities for growth and learning. To understand a particular tradition, we often have to compare and contrast that tradition with an opposing one. For example, if we want to understand Islamic law, it behooves us to study it alongside Western law and its traditions.

Third, both immigration and technology is making the world smaller and smaller, and so we encounter all manner of national and cultural diversity as a matter of course. Consequently, we have to come up with a model of dialogue that will allow us to peacefully coexist. Freedom of religion is needed both within a particular tradition and across traditions. In the Islamic world, Muslims of different sects and traditions should be able to converse and discuss their ideas without fear of force being used to settle the debate. In fact, the debate does not need to be settled once and for all, because we are all on a journey to understand that which we call God.

In Islamism and Islam, Bassam Tibi, a scholar of Islamic thought and law, made a useful distinction between Islamism as a religious movement that deploys Islam as a mode of government and Islam as a spiritual religion that should enlighten the conscience. Islamism as a political movement challenges freedom of religion; Islam as a purely spiritual religion promotes freedom of religion. Islamism hopes to forcibly bring Islam to every household. Islam gives people the agency to exercise faith (or not) according to their own conscience.

I am not an Islamist; I am a Muslim committed to promoting freedom of religion not only within the competing traditions of Islam but also across traditions of faith. I used to be an Islamist when I was living in Yemen, because I was not exposed to any alternative way of being, doing, and knowing in the world. But after living in a pluralistic society such as the United States, I came to appreciate the pluralistic nature embedded in enlightened Islam. I do not need to advocate for freedom of religion from sources within the Western canon because I have a rich Islamic tradition from which I can derive a deposit of gold that long has been forgotten, unfortunately.

But while I was embarking on a journey of understanding freedom of religion, I realized that the United States also has looming problems in this domain. Whether it’s the threat of an angry postliberalism or the illiberal constitution of Yemen, we should not legislate a particular religious point of view for the masses, because that does more harm than good. Religion is better practiced through conscience, not force.

In the Qur’an, it’s understood that God created angels as infallible creatures, incapable of committing any sins and always obeying the commands of God. Moreover, God created devils, who are always disobeying divine commands. Between the angels and the devils, God created humans, whose uniqueness lies in their agency, their ability to act willingly in the world. Granting human beings freedom of choice in religion (or no religion) is inherently good because it accords with the anthropology of humans. It is in our essence to make a choice—either to obey or to disobey, to act as angels or as devils.

Since I transitioned from being an Islamist to a Muslim, I disconnected from my roots in Yemen, which desperately and seriously needs to consider the benefits of freedom of religion. Most of the problems of Yemen can be addressed by embracing an attitude that is congruent with human nature—our nature to sin, to make mistakes, and to act as humans. Unlike Yemen, Morocco enjoys freedom of religion, as evidenced by its Marrakesh Declaration of 2016, a conference whose landmark decision restated the liberal Islamic belief in the rights of minority religions and unbelievers to exercise their freedom of conscience. It condemned the restrictions and violence against them by many Muslim states as a perversion of Islam.

Any ideology that does not respect the human person as made by God will result in disaster, as we have seen in the ongoing civil war in Yemen. Therefore, freedom of religion is aligned with how we are made as humans—which is to say that freedom of religion is inherently good.