Today, April 3, 2023, is the 50th anniversary of the commercial introduction of cellphones. On this day in 1973, Martin Cooper of Motorola used a cellphone to place a call from Manhattan to the headquarters of Bell Labs in New Jersey. This simple act ushered in the age of cellphones worldwide. Today there are more than 5.3 billion people in the world using cellphones —a number almost equivalent to the active adult population of the entire world. The 5.3 billion figure represents the number of unique users; the actual number of cellphones exceeds the world population of 8 billion because many people have more than one such device.

We all know the many conveniences cellphones afford us. We’re able to be in constant touch with friends, family, and colleagues no matter where we go. Many kinds of connectivity have flourished via cellphones. Beyond voice communications, we now text and email, and exchange photos, videos, and files through our phones. The way the cellphone has transformed our lives for better and worse is a frequent topic of commentary and reflection.

What’s less noted is the dramatic impact the advent of the cellphone has had on global inclusiveness and prosperity. To appreciate this, we need to look back 50 yearsto when the global population stood at 4 billion people. At that time, there were close to 300 million landline phones in distribution, more than 90% of which were in the wealthiest nations: the U.S., Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Australia, and the nations of Western Europe. In other words, about 10% of the world’s population enjoyed the use of 90% of the phones. At that time, 1 in 1,000 people had a cellphone in the low-income nations of the world, places like India, China, Pakistan, the countries of Africa, and the like. Today, although the wealthy world has far better access to education, housing, healthcare, transportation, nutrition, and other day-to-day necessities as compared to the poorest of the world, there is nevertheless a rough parity between rich and poor when it comes to cellphone use. By “rough parity,” I mean about a 10% difference. That is, roughly 80% of the overall population, including children, in wealthy nations have cellphones, and about 70% of the low-income world do as well.

Technologies generally spread from the rich (who can afford to be early adopters) to the poor. Someone who saw immediately what cellphones could mean in the hands of the poor and labored to get them early into the hands of some of the lowest-income people was Iqbal Quadir, now a senior fellow at Harvard University. His proactive efforts can shed light on the full impact of the cellphone for global progress.

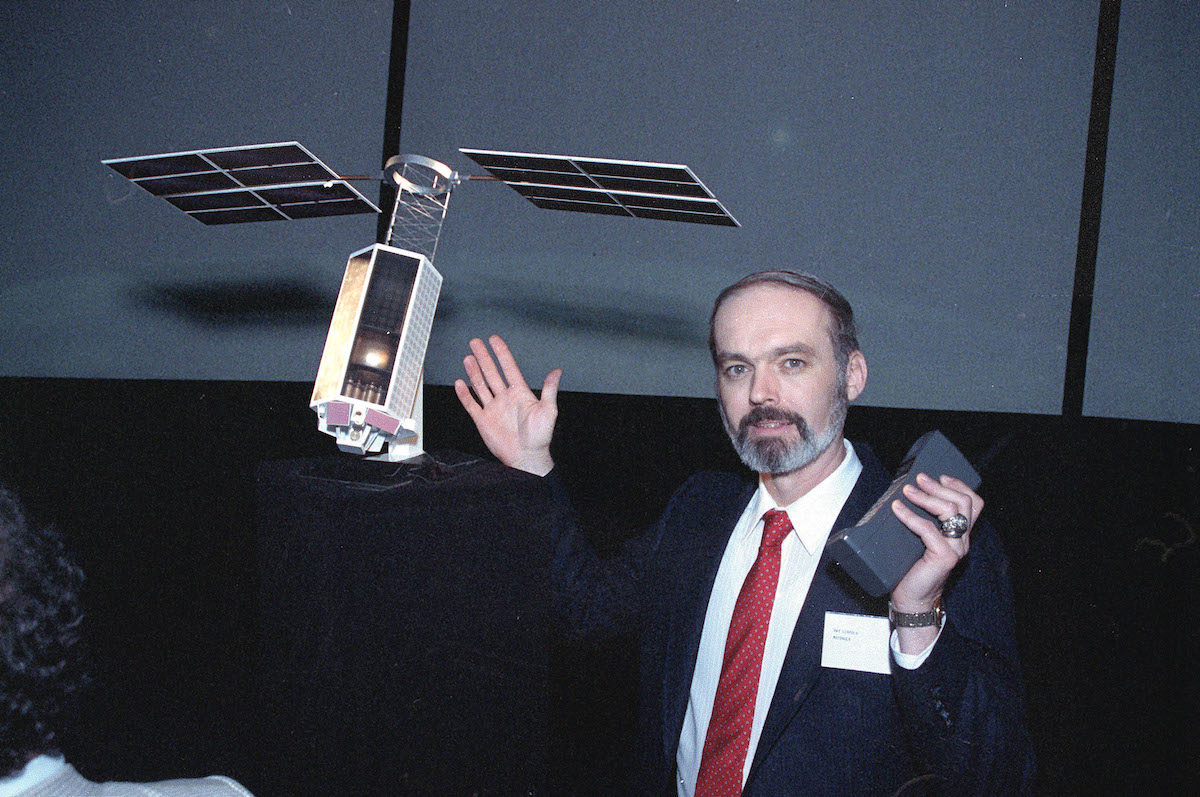

In 1992 cell service began to be digitized. Quadir, at that time an investment professional on Wall Street, was familiar with Moore’s Law. Named for Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel who passed away late last month, Moore’s Law expects processing power to double—and prices to halve—every two-year period. For example, $1,000 worth of microchips today could be available for $1 in 20 years. Quadir reasoned that using increasingly cheap processing power would swiftly give cellphones more capabilities, including making them both more user-friendly and affordable for low-income people.

Quadir abandoned his lucrative Wall Street career and plunged into a new mission: to bring cellphones to every corner of his native Bangladesh in 1993. The country had about 120 million people at that time, and roughly one phone for every 400 Bangladeshis. To understand the uphill struggle Quadir’s vision represented, it is enough to say that in 1993, a digital cellphone cost about $500, while the per capita GDP of Bangladesh was less than $300. In 1993, even in the wealthy United States, only 1% of people used a digital cellphone. No one thought they could be sustainably introduced into Bangladesh. Nevertheless, Quadir reasoned that a digital cellphone would be supremely useful to the lowest income people. If such phones could be made available to poor people, their lives would improve and their incomes would rise, which would in turn translate into the ability to pay for cellphone service. Just as ice hockey legend Wayne Gretzky as been quoted as saying that he focused on where the puck was going to be and not where it had been, in 1993 Quadir could see where cellphones would be in a decade’s time, and started from there.

Quadir particularly wanted to reach his country’s poorest. He approached Grameen Bank, a microcredit organization, which lent to the lowest-income people. He named his new cellphone company “Grameenphone” at the request of the bank. Today that company serves just under 50%, or more than 80 million, of the phones in Bangladesh, a country that has slightly more phones than its population of 165 million. Everyone recognizes that Bangladesh has been transformed, and the GDP per capita is now approaching 10 times as much as in 1993—close to $3,000. There are other factors that have contributed Bangladesh’s progress, but Quadir’s introduction of mass communication tools has undoubtedly been a prominent transformative force.

One can discern five significant, positive benefits of putting cellphones into the hands of the poor. First, it improves people’s lives, as they are better able to keep in touch with friends and family. Second, it allows a user to accomplish more in less time, allowing her to earn more by making her more efficient. Third, higher earnings allow her to pay for the cellphone service, and this connectivity makes it possible for commercial ventures to take root and prosper. Fourth, higher earnings of individual consumers add up, giving rise to higher GDP for the country. Fifth, the higher incomes spent on other consumer goods gives rise to entrepreneurs who meet the rising demand. This is the way of economic progress in developing countries.

Quadir thinks that Grameenphone has shown the way to economic growth and that the international community should foster the introduction of other empowering tools. Putting more innovations, such as solar panels, small windmills, even novel medical devices, into the hands of the lowest-income individuals in the world will empower them to develop into more self-sufficient and productive individuals—and will do so not at the expense of the rich but by way of boosting exports. This is no zero-sum game. Here, everyone wins.