Part 3 of my series on poverty and the welfare state ended with a brief look at two community associations in South Dallas. As the Washington welfare-reform impasse in 1995 and 1996 dragged on, I traveled the country learning and speechifying.

I learned much from Deborah Darden and her Right Alternative Family Service Center, based in Milwaukee’s Parklawn housing project with its 518 apartments largely populated by welfare moms. Deborah, a former Jesse Jackson follower, emphasized “learning from our mistakes. Single parenting is not a positive. Letting kids run free is not a positive.”

Deborah introduced me to Parklawn tenants she had influenced. One such tenant, Donna Harris, said she had realized “I shouldn’t be living with a man if I’m not married.” She got married and reflected on her changed thinking: “Used to be, every time I heard the word God, I got mad. Now I know God is the center of everything.” At the Family Service Center’s office, an old basketball court with hoops still on the walls, Michelle Dudley rubbed her braided hair and said, “I used to drink, smoke weed, do the pipe. I thought it was OK to sit home and watch TV all day. My four kids used to be wild. It was because of me. Now I’m getting my GED and nobody’s allowed to do nothing in my house.”

In Autumn 1995, ex-boxer Bob Cote showed me his rundown but immaculate homeless shelter in downtown Denver, Step 13. Bob, 6-foot-4 and excited to display his creation, climbed two steps at a time from the two big dorms on the first floor to an upstairs floor of alcoves with some privacy. Further upstairs were single rooms with windows, awards for those who showed a desire to work and improve their lives. At the end of the process, the formerly homeless had their own bank and telephone accounts, owned their own furniture, and were ready to go out and rent apartments.

Bob said his step-by-step approach accorded with street-level reality: “You don’t just give a street drunk a bed and a meal and some money. He knows how to work the system too well. You’ve got to get him out of his addiction.” Bob spoke from experience: Once he had staggered through Denver’s streets drinking a fifth of vodka and 12 or 14 beers each day. He remembered men vomiting on themselves and passing out. He did the same but finally had “a moment of clarity”: “I’m committing suicide on the installment plan.”

Bob poured out the bottle’s contents and began pouring what he’d learned as a homeless alcoholic into a program that challenged rather than coddled men seen as hopeless. At Step 13, residents who sobered up gained minimum-wage manual labor jobs, then moved to positions with higher pay at local businesses. Meanwhile, they made their beds, cooked their own meals, cleaned up afterward, attended Bible studies, and submitted to random urine screens and Breathalyzer tests. One sign at Step 13 proclaimed: “The day you stop making excuses, that’s the day you start a new life.”

Seeing such underfunded but over-successful (compared to government work) projects pushed me to find ways to increase their financial support without making them rely on either sugar daddies or Uncle Sam. Reliance on big funders, either private or governmental, could easily lead to mission drift. The solution was to find more donors at the $500 level, but few of them had much discretionary money, since many among the most committed tithed to their churches.

While speaking at community events around the United States, I regularly asked audiences this series of questions: If you had $500 to give to any poverty-fighting organization, how many of you would give it to the federal Department of Health and Human Services or some other Washington agency? How many of you would give it to your state government? To city hall? How many of you know of some community-based, nongovernmental group that would do a better job with that $500?

Only a handful of people wanted governmental bodies to spend the money, and those people were almost always professors. The vast majority wanted to help community groups. I’d then explain that a $500 tax credit would encourage taxpayers to send more money to those small groups rather than to the IRS. Any approach involving government has its dangers, because politicians can demand conformity to government standards. But with Washington vacuuming up so much cash, this seemed like the best bet to shrink it and grow groups. Tax credits are no panacea, but they do empower individuals rather than bureaucrats to allocate funds, and they’re also better than vouchers because the feds never get their hands on the money.

The tax credit proposal gained support from two presidential candidates. Late in 1995 I met with former Tennessee governor and U.S. secretary of education Lamar Alexander, who sought the 1996 GOP nomination. We talked in the Hay-Adams Hotel, created from houses once owned by Secretary of State John Hay and historian Henry Adams. The building had a tragic beginning: Adams’s wife, Marian, committed suicide on the fourth floor in 1885 by swallowing potassium cyanide, and some people say they can still smell the faint almond fragrance. I could not, but when Alexander endorsed the tax credit idea in a speech in Iowa, stating he was “largely inspired by the work of historian Marvin Olasky,” journalists treated his proposal like cyanide. Alexander said: “I’m not just saying Washington welfare should stop. I’m saying we should expect more from ourselves.” Others said such an expectation was unrealistic. In March 1996, Alexander dropped out of the race.

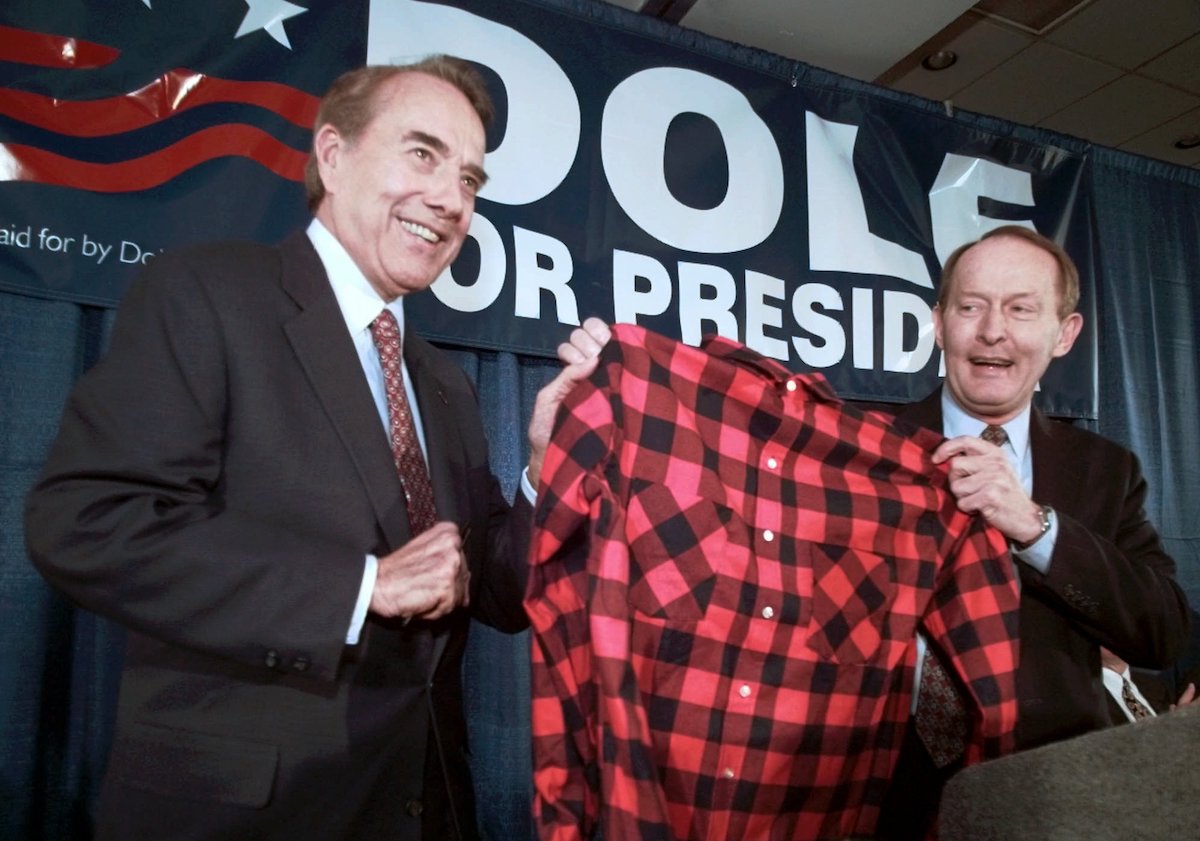

Later, curmudgeonly candidate Bob Dole proposed the $500 tax credit for individuals who earmarked a portion of their income taxes to private and religious charities that serve the poor: “Americans have lost patience with the Great Society, but they have not lost their compassion for the poor.” That was true in the 1990s, and the tax credit idea added a note of financial realism regarding an extension of compassion, but Dole’s dull campaign did not engage many hearts.

What was realistic? The Washington Post’s William Raspberry understood that “government may be incapable of doing welfare in a way that doesn’t make bad matters worse.” He wanted to “help poor people in a way that might even enhance their chances of achieving independence.” He said successful programs “might look a lot more like private charity than the public dole. … Private charity—whether foster care, self-help centers, or gospel-oriented soup kitchens—manages at least some of the time to turn lives around.”

I met with other members of the D.C. journalistic elite, hoping to enlist in a conscience-raising campaign David Broder, Charles Krauthammer, Mort Kondracke, and others. They responded with sympathy but skepticism. New York Times columnist Peter Steinfels said it the clearest: “Olasky and his allies see … a vast outpouring, from millions of Americans, of personal commitment. … It is an inspiring vision, but is it realistic?”

My observing and speechifying in 30 states gained me platinum status on Delta (at least 100 flights per year) and a little Johnny Appleseed success. For example, Broadway Community (BCI), a program on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, began when executive director Chris Fay was searching for new ideas: “I was working with the poor and was burnt out. We saw the same people coming for food, year after year. We saw very few breakthroughs. The people who volunteered for the soup kitchen didn’t know anything about the individuals who ate there. We were doing it to feel better about ourselves.”

Fay learned from history and his own experience the importance of offering challenging, personal, and spiritual help that can change lives: effective compassion, in short, rather than affluent guilt relief. In his smaller but better program, participants developed clerical skills and basic computer literacy, and gained training in food service, custodial, and security jobs. I met individuals who worked in BCI microenterprises such as StreetSmart, a mall-cleaning group. Crucially, they had monthly contracts and frequent evaluations.

Since local employers valued the judgment of BCI instructors, BCI could offer guaranteed job placements for those who passed random drug tests for a year. That was too much for nine out of 10 of those who started the program. Fay notes that their average age was 40 and they had been using drugs for 25 years: “They won’t work until they’ve lost everything and have no alternative.” But 60% of those who stuck it out for a month graduated: They could achieve much once they got their minds in gear. Fay said, “I rarely meet anybody who is incapable of working. Many have gotten used to government funding: They have no work emphasis and no purpose in life.”

But I was a feeble sower and often tossed seeds onto stony ground. Once, tired of travel, I asked Richard John Neuhaus, sitting next to me at some event, how he stayed the course. He told me he once complained to his mentor, Abraham Heschel, about going on the road again, this time to Chicago. Heschel froze the rivulet of self-pity with four words: “Richard, go to Chicago.” I got the point and kept going until it was time to return to University of Texas teaching at the end of August 1996.

That was the month Bill Clinton’s political advisers said two vetoes of welfare reform bills were enough: Don’t do anything to let the flailing Dole campaign gain support. (To be continued.)

This is the fourth installment of an eight-part series on poverty and welfare reform in America. Click through for parts one, two, and three.