When the Gestapo was uncovering a left-wing conspiracy to overthrow Hitler, they called it “the Red Orchestra.” But they began to realize that there was another resistance movement of far greater scope, reach, and effectiveness. They called it the “Black Orchestra.” This was a conservative resistance, one motivated largely by the Christian faith.

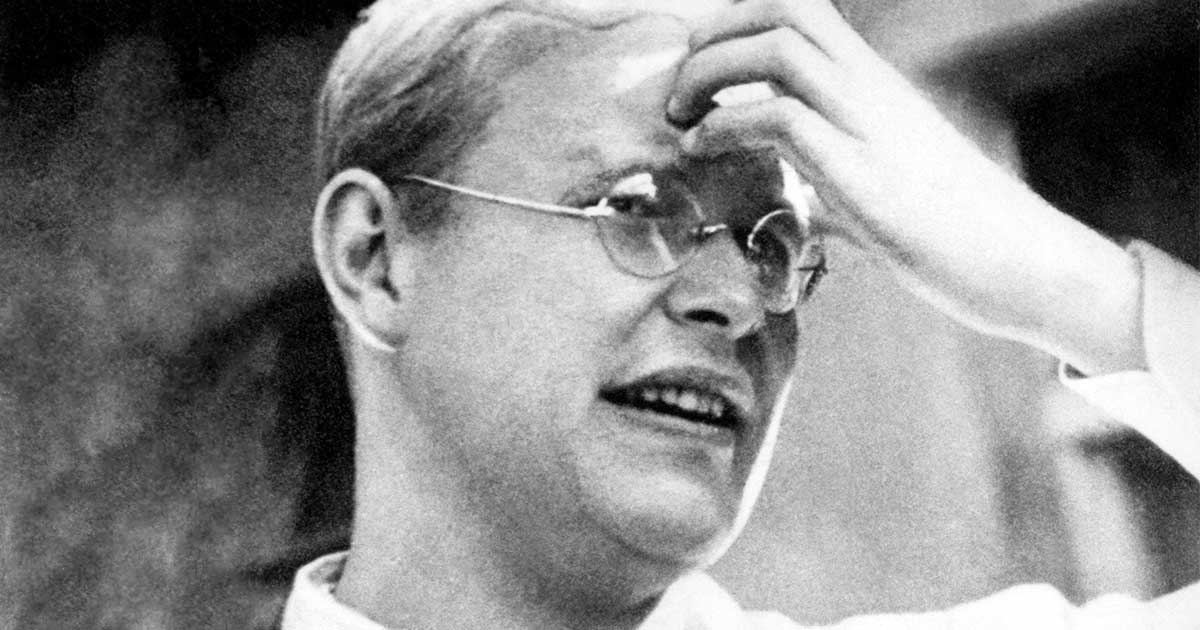

In White Knights in the Black Orchestra: The Extraordinary Story of the Germans Who Resisted Hitler, journalist Tom Dunkel tells the story of this conspiracy, perhaps best known for its failed attempt to assassinate Hitler and that led to the execution of Lutheran theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

My impression had always been that Bonhoeffer was caught up in a quixotic and poorly planned attempt by a small group of German aristocrats and military officers at the very end of the war, and that his role was minimal, basically that of a courier. But Dunkel shows that the Black Orchestra conspiracy began in the earliest days of Hitler’s regime, that it penetrated to the highest levels of the German war machine, and that it carried out many anti-Nazi missions, some of which had an impact on the outcome of the war.

Bonhoeffer and his entire well-connected family were in the thick of it. The conspiracy began with his brother-in-law Hans von Dohnanyi, an attorney at the Ministry of Justice. Soon after the Nazis seized power but before the war, Dohnanyi began documenting their crimes and atrocities in a secret file entitled “The Chronicle of Shame,” which would eventually come to thousands of pages.

He shared what he was doing with his friend Hans Oster, a dashing and energetic officer who was serving as deputy to the head of the Abwehr, the department of military intelligence. They resolved to do something about Hitler and pulled into their circle, remarkably, Ludwig Beck, the army general chief of staff, as well as the man who would become the most important conspirator, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr and the spymaster. Those two, in turn, would bring in others, forming an anti-Hitler network that extended throughout the German military and government bureaucracy.

Meanwhile, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was battling the so-called German Christians, who wished to Nazify the Protestant state church by turning Christianity into a cultural religion (as liberal theologians were already doing) and expunging its “Jewish elements” to the point of removing the Old Testament from the Bible altogether. (This, too, was made feasible by piggybacking on the work of generations of liberal Bible scholars who had succeeded in undermining biblical authority within the state church.)

The conspirators’ first priority was to prevent the war that Hitler was preparing for by staging a military coup. After taking out Hitler and his associates, they would put into place a provisional government, leading to a democratic monarchy headed by Prince Wilhelm of Prussia, the grandson of the kaiser deposed after World War I, who would give the new government legitimacy.

On September 27, 1938, an assault team of 60 heavily armed soldiers was in place, ready to attack Hitler’s residence and overwhelm his 15 guards. The generals wanted Hitler arrested, not killed if it could be prevented, but Oster formed “a conspiracy within a conspiracy” to have him shot on sight. But on the very eve of the coup attempt, Hitler left for Munich to attend the meeting called at the last minute by Neville Chamberlain, during which the British prime minister signed away Czechoslovakia to achieve “peace in our time.”

The conspirators missed their chance. And after another unrelated assassination attempt in November, Hitler greatly ramped up his security precautions as his assaults on Europe began. After taking Austria and Czechoslovakia, Hitler (in league with Josef Stalin, it should be remembered) invaded Poland. France and the Netherlands followed. The bombing of Britain was intended as a prelude to invasion. Russia, ironically, would also become a target, one Hitler would regret. The world was at war—again.

Meanwhile, in Germany, Hitler was implementing his policies first of euthanizing the physically and mentally disabled, and then of exterminating the Jews.

As the nightmare that was Nazi Germany grew worse, the Black Orchestra remained active. Because of his open opposition to the invasion of Poland, Gen. Beck was forcibly retired, though he continued conspiring with his network of military resistors. As Canaris used his anti-Nazi spies to warn the Allies of Hitler’s next moves, the Black Orchestra worked to expose the Nazis’ euthanasia program and to smuggle Jews out of the country.

Meanwhile, Bonhoeffer preached boldly against Hitler and Nazism. After the Nazis and their theological allies took over the state Protestant church, he helped organize the “Confessing Church,” consisting of anti-Nazi pastors and congregations. He was put in charge of a confessional seminary, which went underground after it was closed by the Nazis, who then forbade Bonhoeffer to speak in public and began the process for drafting him into the military.

To protect him, Canaris made Bonhoeffer an Abwehr agent! His pretext was that he needed a spy to keep tabs on the Confessing Church, but he actually sent Bonhoeffer on missions to Italy and Switzerland to funnel information to the Allies. When the Lutheran bishops and pastors in occupied Norway protested Nazi policies, Bonhoeffer was sent there to assess the situation, but his real mission was to encourage the resistance. When Dohnanyi lost his position in the justice ministry for refusing to join the Nazi party, Canaris brought him into the Abwehr also. Canaris even used this gambit to help Jews escape, signing them up with the Abwehr claiming he was sending them to spy on the United States!

Canaris formed a secret division of his intelligence organization—“Department Z”—just to run the conspiracy, putting Oster in charge. Contrary to the picture of sinister Nazi agents that we get from World War II spy movies, Hitler’s spymaster and much (though not all) of the intelligence agency he operated played major roles in the anti-Nazi resistance.

After three more failed attempts to assassinate Hitler—a time bomb put on Hitler’s plane failed to go off; a suicide bomber’s fuse malfunctioned; an explosive vest was destroyed in an Allied air raid before another suicide bomber could use it—the conspiracy began to unravel. The Gestapo, Hitler’s secret police, started connecting the dots.

Bonhoeffer, Dohnanyi, and some others were arrested and imprisoned and awaited trial. Bonhoeffer wanted a speedy trial, confident that he would be released, but Dohnanyi, more realistically, knowing a trial would end in execution, wanted delays, hoping that an Allied victory—which by now seemed inevitable—would save his life. He went so far as to infect himself with diphtheria with the help of his wife, Bonhoeffer’s sister, who as a scientist had access to infectious bacteria. He reasoned that his chances would be better with a dangerous disease, since the Nazis would not risk being in a courtroom with him.

Hitler finally dissolved the Abwehr, moving all its functions to the SS, which had its own intelligence division, the SD. Canaris and Oster were both put under house arrest.

Despite these losses to their ranks, the Black Orchestra planned one last performance even though defeat in Russia and the D-Day invasion meant an Allied victory was imminent. The conspirators attempted one more coup and one more assassination because, as they said, it was the right thing to do. The plan was codenamed “Operation Valkyrie.”

A new leader of the resistance had emerged—the charismatic young officer Claus von Stauffenberg, deputy of the army reserve, the head of which was also a conspirator. In that capacity, Stauffenberg attended planning meetings with the Führer. The conspirators, who now included Germany’s best combat general, Erwin Rommel, who was in charge of the D-Day defense, put everything in place for a provisional government to surrender to the Allies once Hitler was dead.

On July 20, 1944, Stauffenberg, summoned to Hitler’s personal compound, known as the “Wolf’s Lair,” carried a briefcase full of plastic explosives connected to a timer. He set the briefcase under the table and excused himself to make a phone call. The bomb exploded, destroying the building. Yet Hitler—scorched and bleeding, with his pants torn to shreds—somehow survived.

Furious, Hitler embarked on a final purge. Himmler, head of the SS, launched a commission to stamp out all internal enemies. In the course of these investigations, Dohnanyi’s “Chronicle of Shame” was discovered in a safe. Canaris’ war diaries were also found, giving details of the conspiracy and naming the conspirators. Everything came out.

Hitler demanded that those who had already been arrested—such as Dohnanyi and Bonhoeffer—be immediately tried and given the death penalty. Beck, Rommel, and other generals were allowed to commit suicide. Dohnanyi was hanged at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. On April 9, Canaris, Oster, and Bonhoeffer (who, ironically, had nothing to do with Operation Valkyrie, having been locked up for two years), along with three others, were hanged at the Flossenbürg camp.

Two weeks later, the camp was liberated by Allied forces. A week after that, on April 30, Hitler killed himself in his bunker.

The July 20 commission arrested some 7,000 conspirators, 5,000 of whom were put to death. Were their deaths, as well as their anti-Nazi activities, ultimately in vain? Not necessarily.

That German intelligence was led by the conductor of the Black Orchestra had its effect. Canaris told Hitler that Great Britain had 39 divisions ready to fight an invasion, dissuading him from invading. The Brits really had only 16. Hitler sent Canaris to Spain to persuade Franco to enter the war. Instead, Canaris convinced him to stay out of it. Canaris was so bold as to hold clandestine meetings with some of his counterparts in Allied intelligence. We will never know his full contribution to the Allied victory.

In addition, the Black Orchestra informed the Allies about the German V-1 and V-2 missiles and where they were being manufactured. That location was thoroughly bombed.

When Hitler shut down the Abwehr, many agents loyal to Canaris, including those not part of the Black Orchestra, preferred to join the army instead of the SS, which was not up to speed on military intelligence. This meant that the Germans had big gaps in their intelligence regarding the D-Day invasion and its aftermath. And by that time, Rommel, who commanded the defense, had already been drawn into the conspiracy. He did not conduct that campaign with the same brilliance he had shown in North Africa, which might have been deliberate.

After the war, the Allies found 1,500 pages of Dohnanyi’s “Chronicle of Shame.” This was used as evidence in the Nuremburg trials, leading to the conviction of 36 war criminals.

Bonhoeffer’s writings and correspondence while in prison were saved and published. His partially finished Ethics and his Letters and Papers from Prison are arguably his finest and most enduring theological works.

In an afterword to White Knights in the Black Orchestra, Dunkel says that this is “a work of traditional narrative nonfiction, meaning no liberties were taken with the historical record.” He does not make up dialog, after the manner of some, nor rearrange events to make a better story. His narrative, though, is vivid and moving, depicting the everyday lives of the people he writes about—including Bonhoeffer’s romance with his fiancée, Maria von Wedemeyer, who was permitted to visit Bonhoeffer regularly in Tegel prison—as they are caught up in the growing horrors of the Nazi regime.

That National Socialism is thought of today as an extreme kind of conservatism is one of the biggest victories of Marxist propaganda. This book shows that Hitler and his followers were radical revolutionaries, who sought to liquidate—not conserve—the traditional Western values of faith, morality, and freedom.

Dunkel does not play up the conservative and Christian angle as such, beyond saying that the conspirators “tended to be politically conservative to the bone” and describing the key figures as devout Christians.

He also cites the motives some of the conspirators themselves gave at their trials, just before their executions: “This was my duty as a Christian who wanted peace,” said Bonhoeffer. Dunkel describes how Lt. Peter Yorck addressed his judge, “pointing out that the root issue was a totalitarian government’s assertion of supreme authority over every citizen, ‘which forces him to renounce his moral and religious obligations to God.’”

That root issue can appear in many guises, and it must always meet resistance.