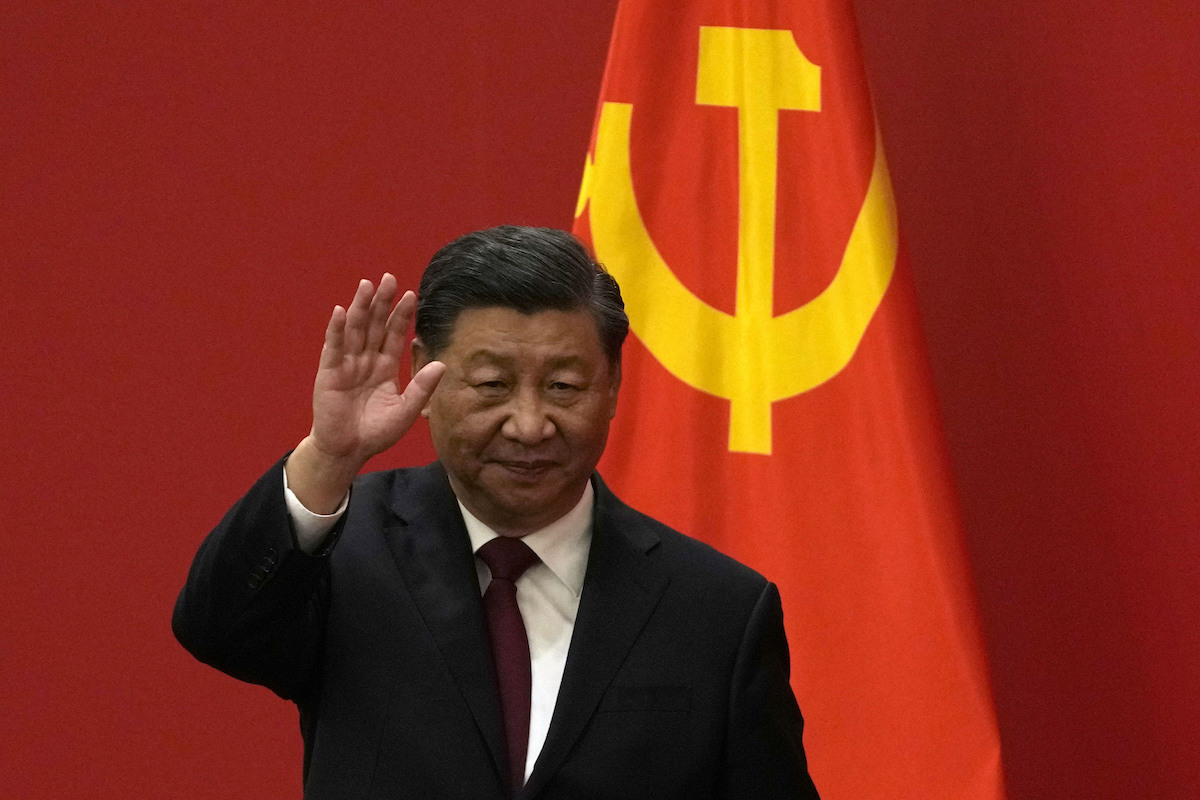

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) held its 20th national congress to chart its future direction and anoint Xi Jinping as leader-for-life. At least that’s what Xi plans. Xi lauded his record, which, he insisted, has “ensured that the party will never change in quality, change its color, or change its flavor.” Under Xi, the CCP’s quality, color, and flavor are all the same: brutal repression.

Yet China’s future is not set in stone. Indeed, Beijing’s course, largely determined by the top leadership, has been extraordinarily volatile. Mao Zedong came to dominate the CCP and thus the new communist government and created what likely was the world’s deadliest tyranny, killing tens of millions and holding hundreds of millions in bondage. However, within a decade or so after his death in 1976, the more pragmatic Deng Xiaoping gained ascendency and created a much freer society (though still politically oppressive). The Mad Mao horror show was over and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) opened to the world, proceeding on the path to global engagement. In the following decades, Deng’s two handpicked successors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, largely maintained that model.

Now Xi has turned sharply back, toward stultifying Maoist political controls, though without “the Great Helmsman’s” radical unpredictability and, even more important, mass murder. More consequential for the rest of the world, though, under Xi the PRC has become more assertive internationally, while creating a military second only to America’s, posing a potentially greater threat to free societies. In the view of some Washington policymakers, this creates the specter of a permanent enemy, bound to oppose the U.S. throughout the 21st century.

But Xi, 69, will not rule forever. And when he goes, whether through death, retirement, or coup, the PRC’s future will again be in play. Although his authority today appears as great as Mao’s, he lacks the latter’s foundational revolutionary role, and therefore could be more easily consigned to the past. Although Xi’s successors still could maintain, or even intensify, his policies, they could also return to a more liberal path. China’s history leaves open the possibility of positive change.

Keep in mind: The CCP began abandoning Mao’s policies almost immediately after his death. More moderate leaders arrested the infamous “Gang of Four,” including Mao’s widow, who were leading proponents of his deadly and destructive Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. This decisively ended Maoist politics. His philosophy, in contrast to his pervasive imagery, also did not survive his death. The twice-purged Deng enjoyed the ultimate revenge, coming to power and engineering his country’s radical transformation away from Maoism. Even after the Tiananmen Square crackdown, which crushed protests nationwide and resulted in a widespread post-massacre purge, the PRC remained relatively open to the world and preserved space at home for disagreement, if not outright dissent.

Similarly, the 1953 death of the Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin, who competed with Mao for title of the world’s most prolific killer, led to substantial liberalization despite the continuing Cold War. Even more might have changed, ironically, had Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria, who headed the NKVD (forerunner of the KGB) during Stalin’s paranoid Great Terror, not been purged. Oddly, he was the advocate of more radical reform and might have ended the Cold War—for instance, he favored a united, neutral Germany. However, he was arrested in a palace coup with the assistance of the military and later executed.

The victor in the ensuing power struggle, Nikita Khrushchev, was seen as a reformer for undertaking the process of “destalinization.” However, that merely represented a move back toward the more normal political, social, and economic authoritarianism that predated Stalin. Essentially, Moscow returned to the world of Lenin and the early Bolsheviks, brutal authoritarians whose violence was at least somewhat constrained. Still, Khrushchev ruled with a lighter touch than Stalin during an earlier and more limited version of perestroika and glasnost—even allowing publication of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s work—until Leonid Brezhnev organized a political coup on behalf of stasis. Communism’s end then had to wait for Mikhail Gorbachev’s rise.

These experiences give hope for the PRC. The Cold War ended when it did because of human decision, not inexorable forces. The USSR’s collapse very likely would have been delayed had a more traditional apparatchik than Gorbachev taken over as Soviet leader in 1985.

Where China will end up is impossible to predict. It is notoriously difficult to measure public support in authoritarian systems, but the CCP and government appear to have substantial popular backing, based on delivery of economic growth and gain of national respect. However, such positive sentiments may be fragile. What happens if the economy stagnates or declines, which appears likely, or the regime suffers a significant international setback? During much of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Xi government gained credit for its apparently competent and effective response. Now, however, Beijing is facing significant discontent with its continued policy of mass lockdowns.

Xi and the CCP claim to—and probably do—believe that destiny is on their side. However, human experience reaches a contrary verdict. The accelerating headwinds facing the PRC offer support for such skepticism. But it would be foolish to dismiss China’s potential for continued growth. Despite far greater internal weaknesses, the Soviet Union stumbled along for decades.

Nevertheless, recognition that China’s future is not fixed gives those committed to a broadly liberal order both incentive and time to act. The possibility of change also argues against reflexively mimicking Beijing’s enthusiasm for statist intervention. Rather, those committed to a freer, more democratic society should treat China’s future as a battle over ideas that, hopefully, can be won.

Advocates of reform should play the long game. Free societies should improve their modeling of democratic values and encourage a greater information flow to the Chinese people, online and off. Liberal peoples and nations should contest claims that the “Beijing Consensus” offers a better model of development and governance. America, Australia, Europe, and other open societies should welcome Chinese visitors, especially students.

At the same time, it is important to act carefully in addressing the PRC. Making what are perceived to be existential threats ensure a more hostile and fevered response from Beijing. Unnecessarily antagonizing the Chinese public—even the young resent foreign criticism of their country, just as Americans dislike insults levied against the U.S. from abroad—aids the CCP’s attempt to don the mantle of Chinese nationalism.

The internal battle for the PRC’s future will ultimately be the most important determinant of China’s future. Over the long term, Beijing is likely to pose a more serious challenge than did the Soviet Union. However, the former’s course is still open. Free peoples around the world should ponder how to encourage the potential Chinese colossus to empower its people rather than its rulers. Most important will be a sustained effort to engage the Chinese people, who ultimately must decide their own future.