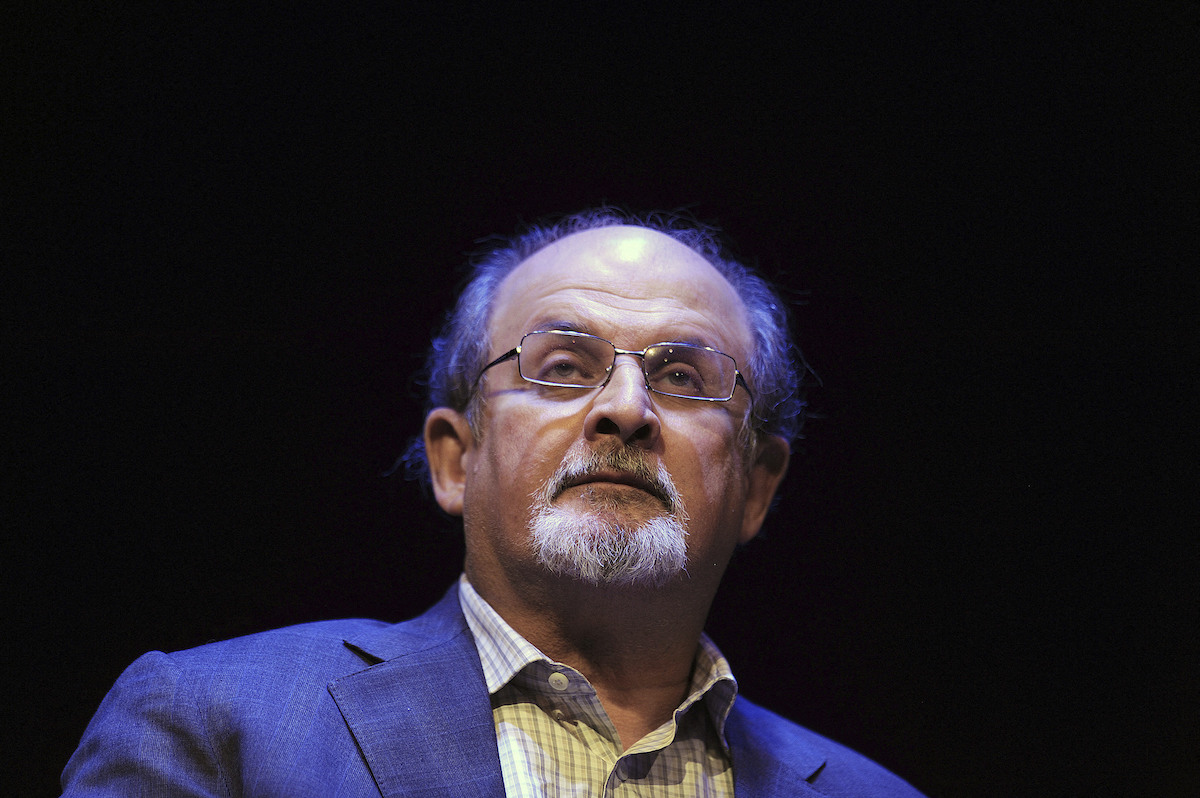

It seems that the infamous “death fatwa” that Ayatollah Khomeini issued against Salman Rushdie back in 1989 for his novel The Satanic Verses, which most Muslims found offensive, finally reached it mark on August 12 in upstate New York. Seconds after the award-winning author appeared on stage at the Chautauqua Institution, to deliver a lecture on artistic freedom, he was attacked by a man who stabbed him multiple times.

Luckily, Rushdie survived the attack—albeit with serious wounds and the possible loss of an eye. But the worldview that made this violence possible needs to be addressed in an honest conversation. That is not only because the man who targeted Rushdie, Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old American citizen with Lebanese origins, is reportedly a sympathizer of the Iranian regime, whose official newspaper, Kayhan, sent “a thousand bravos … to the brave and dutiful person who attacked the apostate and evil Salman Rushdie.” It is also because those in similarly militant circles, from Pakistan to Turkey, have celebrated the attack, demonstrating that there is a conviction in some parts of the Muslim world today that “those who insult Islam,” especially its Prophet, deserve to be killed.

Surely it would be wrong to attribute this grim view to all Muslims. It is no wonder that various organizations—from the Muslim Council of Britain to Muslim leaders in Michigan—condemned the attack from the first moment. A group of Islamic intellectuals from Iran even released a bolder criticism of any “assassination in the name of Islam” and all kinds of “despotic rule” in the name of the faith. These are just a few refreshing voices among many.

These diverse views confirm the truism that there are both “moderate” and “extremist” elements in Islam today, as probably is the case in other traditions. But the spectrum is actually a bit more diverse; even in the simplest categorizations, we can speak of not two but at least three different stances on the thorny issue of blasphemy.

First, there is the extremist stance, which holds that anyone who dares to insult Islam, especially the Prophet Muhammad, deserve to be killed—even by vigilante justice. Examples of such “justice” include terrorist attacks in Europe against satirical publications like Charlie Hebdo, mob violence in Pakistan and elsewhere against perceived blasphemers, and the very death fatwa against Salman Rushdie.

Second, there is the mainstream conservative stance, which holds that insulting Islam is indeed a capital crime—but it can be punished only by courts, with due process, not by terrorism or mob violence. This is the common view one hears from mainstream clerics, both in the Sunni and Shiite world, as well as from most statesmen and opinion leaders.

Third, there is the liberal-reformist stance, which holds that while insulting Islam is morally reprehensible, we can’t treat it as a crime. People say what they say, and the right Muslim response is either to counter criticisms with reason or to ignore sheer vulgarness with dignity.

Needless to say, I subscribe to the third view.

A key reason is that I believe we Muslims will gain respect for our faith not by violently or coercively punishing blasphemers but by pardoning them. This will prove a sign of our confidence in our faith and a demonstration of its magnanimity.

To some Muslims, this may sound unnecessarily meek, but its support comes from none other than the most authoritative source in Islam: the Qur’an. To be sure, in its more than 6,200 verses, the Qur’an sometimes orders Muslims to “fight the unbelievers”—but only in a context of active war. However, when the Prophet Muhammad and the first Muslims heard verbal insults from their adversaries—primarily Arab polytheists, but also certain Jewish tribes of Medina—the Qur’an ordered mild responses. A Medinan verse tells Muslims that to be insulted is a “test” that they should bear:

You are sure to hear much that is hurtful from those who were given the Scripture before you and from those who associate others with God. If you are steadfast and mindful of God, that is the best course. (3, 186)

Commenting on this verse, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, the great 13th-century exegete of the Qur’an, wrote that while some jurists considered it “abrogated” by belligerent verses, others, himself included, did not think so. He also supported it with other verses of the same spirit. One is the commandment, “Tell the believers to forgive those who do not fear God’s days” (45:14). The other is a description of the believers as “the servants of the Lord of Mercy … who walk humbly on the earth, and who, when the foolish address them, reply, ‘Peace’” (25:63).

Yet perhaps the most specific commandment of the Qur’an against blasphemy comes in verse 4:140, which tells Muslims what they should do when their religion is ridiculed:

If you hear people denying and ridiculing God’s revelation, do not sit with them unless they start to talk of other things, or else you yourselves will become like them.

“Do not sit with them.” That is the Qur’anic response to blasphemy. It isn’t killing. It isn’t even censorship.

Even so, Islamic law—the Sharia, as interpreted by medieval jurists—offers a harsh verdict on blasphemy. All four Sunni schools of law, as well as the Shiite schools, largely agree that sabb al-rasul, or “insulting the Prophet,” is a capital crime. They only differ as to whether those who insult the Prophet can be forgiven if they repent. Some allow repentance; others do not. Ayatollah Khomeini was following the harder line when, after he issued his “death fatwa” on Rushdie, he added: “Even if he repents and becomes the most pious Muslim on earth, there will be no change in this divine decree.”

If this harsh verdict did not come from the Qur’an, where did it come from?

As in the case of apostasy—another burning issue when it comes to freedom in Islam—the verdict came from the reported Sunna: the example of the Prophet Muhammad, reported in narrations that were canonized more than a century after his death, either in books of hadiths (“sayings”) or al-sira al-nabawiyya (prophetic biography). These sources do include stories of the Prophet Muhammad ordering the execution of some blasphemers during the formative years of Islam. In particular, the story of Ka’b ibn al‐Ashraf, a Jewish poet in Medina, whose execution by Muslims is narrated in the most authoritative hadith collection, Sahih al-Bukhari, has been taken by medieval jurists as the iconic precedent to execute blasphemers.

However, a careful reading suggests that “poets” such as Ka’b ibn al‐Ashraf were not killed merely for mockery and insult but also for inciting Arab polytheists to go to war against the nascent Muslim community. This argument was first made by the 15th-century Hanafi scholar Badr al‐Din al‐Ayni and is echoed by today’s liberal reformers. Imam al-Ayni wrote that poets such as Ka’b “were not killed merely for their insults [of the Prophet], but rather it was surely because they aided [the enemy] against him, and joined with those who fought wars against him.”

More significantly, there are also incidents in Prophet Muhamad’s life in which he did not punish blasphemous words when they were just words. According to a narration in Sahih al-Bukhari, a Jewish tribesman in Medina used a play on words when greeting the Prophet. Instead of as-salamu alaika, or “peace be upon you,” he said, as-samu alaika, or “death be upon you.” Hearing this, some companions lost their tempers and asked: “O God’s Apostle! Shall we kill him?” The Prophet said no and told them to respond simply by saying wa alaikum, or “on you, too.” In another version of the same story, the Prophet also said, “Be gentle and calm … as Allah likes gentleness in all affairs.”

In another incident, a man named Dhu’l-Khuwaisira publicly blamed the Prophet for committing injustice. One of the companions, again zealous to protect the Prophet’s honor, asked permission “to strike his neck.” The Prophet stopped Umar, saying, “Leave him.” Remarkably, a contemporary Salafi website narrates this incident, adding: “Such words would undoubtedly deserve execution, if anyone were to say them today.” In other words, it admits that some of today’s Muslims can be much less lenient than the Prophet himself.

But if I believe the Prophet’s leniency should not be ignored, as “gentleness in all affairs” seems to be what both he and the scripture taught—especially in the face of “hurtful” words, which the Qur’an already informed Muslims they will keep hearing.

Therefore, my answer to the question in the title, Would Prophet Muhammad punish Salman Rushdie? is negative: I believe he would not. And in his magnanimity, he would perhaps impress upon people like Rushdie, who calls himself a “hardline atheist,” the virtues of faith.

For the same reason, I believe that both the extreme stance about blasphemy, which justifies terrorism, and the mainstream conservative stance, which justifies legal punishment, are wrong. What Muslims need is the liberal-reformist stance, which is truer to both the spirit of our scripture and the universal dictates of reason.