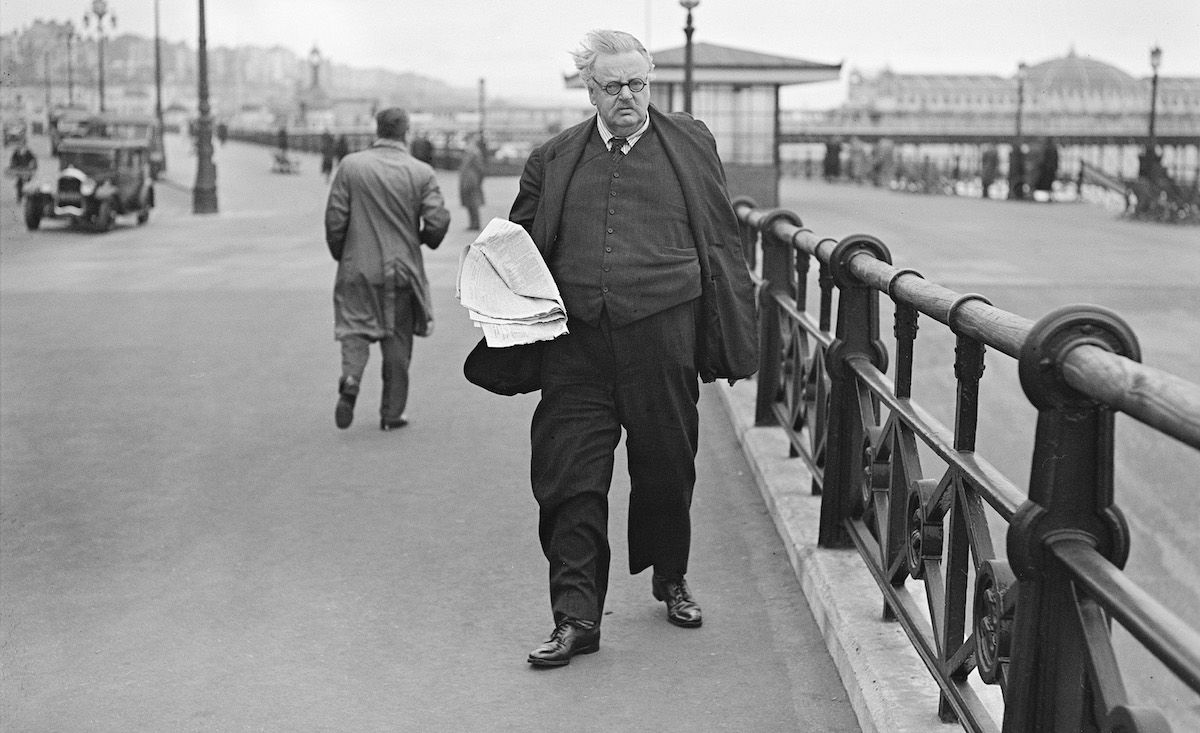

This Sunday, May 29, marks 148 years since the birth of English author G.K. Chesterton. Although he was baptized into the Church of England, Chesterton’s family was not particularly devout and his faith didn’t develop until later in life. After his marriage in 1901, he returned to Anglicanism and later, in 1922, was received into the Catholic Church. His 1908 book Orthodoxy outlines many points of his thought and chronicles how his intellectual journey ultimately found its destination in Christianity.

Chesterton’s somewhat densely packed style, heavy on paradoxes and antitheses, rewards slow consideration. Two ideas I want to dwell on briefly are found in the early chapters of Orthodoxy and reveal something of how careful thought is expressed in rational discourse. The first idea is from the third chapter, aptly titled “The Suicide of Thought”:

That peril is that the human intellect is free to destroy itself. Just as one generation could prevent the very existence of the next generation, by all entering a monastery or jumping into the sea, so one set of thinkers can in some degree prevent further thinking by teaching the next generation that there is no validity in any human thought.

That sounds relevant enough, but, considering that Orthodoxy was published in 1908, I’m tempted to ask—What stage of this process have we reached now? If Chesterton saw over a hundred years ago a generation imperiling thought itself, where have the heirs of that generation brought us? Many have already spoken of the sorry state of civil discourse, or even of any rational discourse, in our time. The intellectual attitude, if you will, that Chesterton describes would certainly seem to have some bearing on this.

I’ll return to that thought in a minute, but first I want to make reference to one more quote from Orthodoxy, this time from chapter 2:

There is a very special sense in which materialism has more restrictions than spiritualism. Mr. [Joseph] McCabe thinks me a slave because I am not allowed to believe in determinism. I think Mr. McCabe a slave because he is not allowed to believe in fairies. But if we examine the two vetoes we shall see that his is really much more of a pure veto than mine. The Christian is quite free to believe that there is a considerable amount of settled order and inevitable development in the universe. But the materialist is not allowed to admit into his spotless machine the slightest speck of spiritualism or miracle. Poor Mr. McCabe is not allowed to retain even the tiniest imp, though it might be hiding in a pimpernel.

The scientism that Chesterton is referring to here has certainly not gone away since his time. One of its effects, visible in many contexts, was for education to be understood as merely the learning of facts rather than also learning how to think or educating the whole person.

As for what the heirs of that “thoughtless” generation have brought us so far, there could be any number of responses, but one worth pointing out is that even the idea of education as merely the learning of facts appears to be giving way. What seems to be gaining in importance instead is not what one knows about an issue or a subject but what one feels about it. When we discuss ideas, in the political or academic sphere, we’ve lost a shared vocabulary, and beyond that even a shared idea of what discourse is supposed to lead to, what its telos, or ultimate end, is. Each side in any debate offers its feelings, its reactions, its performative outrage or enthusiasm, and thinks those emotions are a sufficient statement of both importance and purpose such that a well-reasoned argument would be a sign almost of weakness.

Thus thought and discourse have gone from reasoning to learning of facts to expression of feelings. If each generation depends on the previous one in a physical sense, it’s also true intellectually. We now have a responsibility to educate, or re-educate, a generation in what real discourse looks and sounds like, and to make sure those lessons are passed on to the future. In this, G.K. Chesterton is a valuable guide.