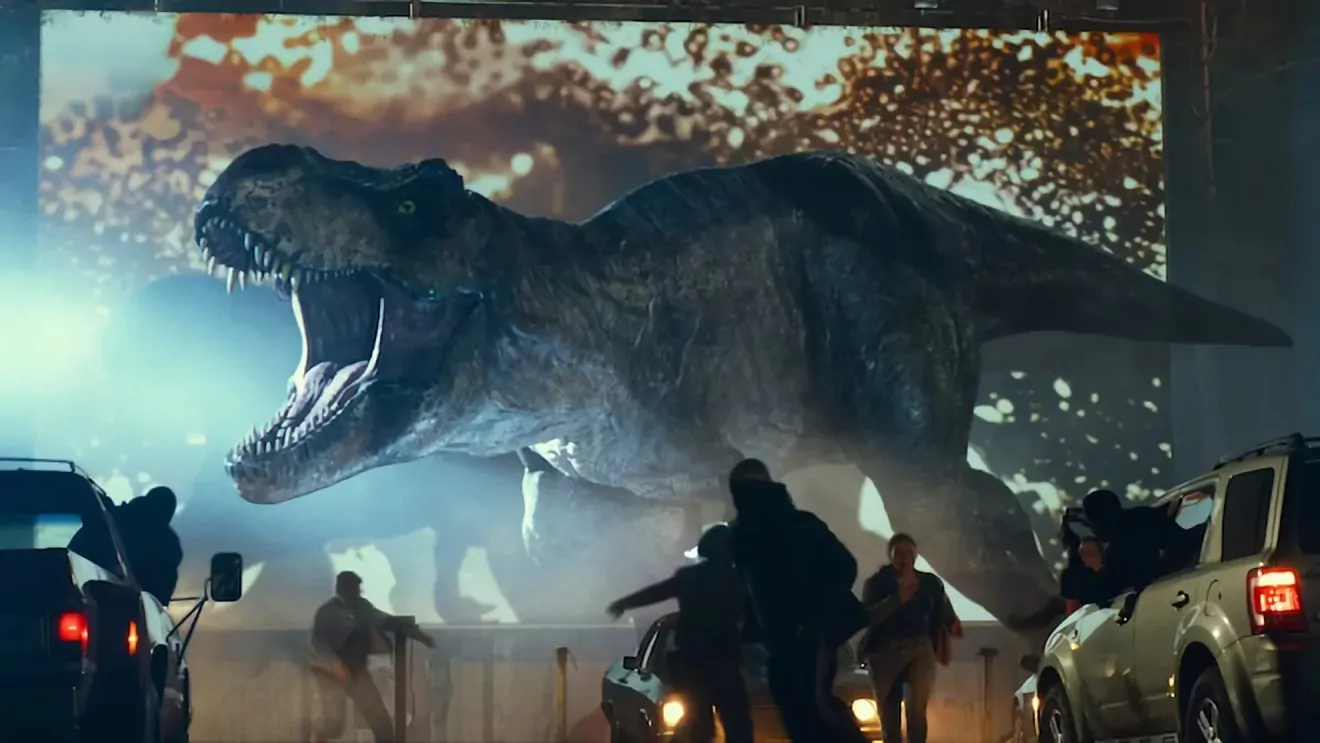

In case you missed it, there’s an official trailer out for the next (and supposedly final) installment of the Jurassic Park saga. Jurassic World Dominion, in theaters June 10, may be your last chance to enjoy the larger-than-life danger, drama, and dinosaurs adventure paired seamlessly with John Williams’ classic musical score on the big screen.

While the case can be made that the Jurassic Park movies have served only as an excuse to show thrilling chase sequences and large-scale destruction caused by the unfortunate confluence of giant extinct monsters and obstinate humans, these movies can also spark reflection on the proper relationship between humans and the natural realm. That’s something a lot of other smart people besides Steven Spielberg have commented on, too.

In the original 1993 film, there’s an iconic scene where Dr. Ian Malcolm protests against the complacent attitude of the dinosaur park creators as utter masters of what they have brought to birth. Marveling at “the lack of humility before nature that’s being displayed here,” Malcolm declares (with true Jeff Goldblum flair): “Your scientists were so preoccupied over whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

Here he’s pointing out the essential link between man as the climax of the created order and man as a moral being. As rational animals, humans occupy the highest rung on the biological ladder, surpassing all other creatures with their capacity for self-reflection and rational choice. The very qualities that signal this legitimate primacy in the natural order, however, are the same ones that give man his moral character and obligation. As the rest of the film plays out, we see how ignoring the moral responsibility to govern our natural environment with wisdom can have disastrous and even gory consequences.

The movie underscores the necessity of preserving the delicate relationship between human nature and the natural realm. And while dinosaurs may not be roaming the streets today in consequence of our getting that relationship wrong, you don’t have to look far in the real world to find many other examples of such distortions. In his 2017 book, In Defense of Nature: The Catholic Unity of Environmental, Economic, and Moral Ecology, Dr. Benjamin Wiker offers a plethora of modern “Jurassic Parks” where the neglect of moral responsibility in our interaction with nature has led to both environmental and human destruction. From sobering analyses of landfills, climate change, and the fable of recycling, to diatribes on the moral pollution caused by the fast food, technology, and pornography industries, Wiker draws from many different sources to demonstrate the inherent connection we humans have with the natural world and the ways we have ignored that connection to our peril. Preaching to both the political left and right, he emphasizes that the natural world (nature “out there”) and human nature (nature “in here”) profoundly impact each other, and we get one wrong to the detriment of the other.

The insights of this book are many, but a particularly compelling one is that a major cause of the modern misunderstanding and misuse of nature (both kinds) can be traced to the thought of Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626). An influential figure in the development of the scientific method, Bacon’s philosophy of science has an insidious flavor. The underlying conviction motivating his efforts was that “nature must be taken apart, so we might rebuild it according to our own desires” (Wiker’s phrasing). Bacon’s goal, outlined in his New Atlantis, seems to be “a kind of techno-utopia” where men have probed and manipulated the natural world to such an extent that they have total control over every natural process and can thus create a paradise on earth. Given Bacon’s infamous line that “knowledge is power,” it isn’t too surprising that the telos of his science is not understanding for its own sake but rather the ability to harness the powers of nature for man’s own purposes—whether for pleasure, economic prosperity, or the thrill of a dinosaur theme park.

Bacon’s ambition to achieve the total domination of nature, while appealing to a technology-infatuated culture, is understandable only to a point. It is true that, as the pinnacle of creation, humans have a level of authority over it and have leave to make use of it to satisfy basic needs. However, as another great British mind once observed, power tends to corrupt. The reality of Original Sin dictates that we cannot survive unscathed when we wield such power without regard for the limits of our own nature.

Who’s Really in Charge?

C.S. Lewis highlights the tipping point of this power struggle in his book The Abolition of Man: “Man’s conquest of Nature turns out, in the moment of its consummation, to be Nature’s conquest of Man.” When a man ignores his moral responsibility and refuses to live within the limits of the natural order, including his own nature, then he has lost the mark of his distinction among creatures. At that point, he is no better than a beast, ruled by whims and passions; raw nature has won out.

Let’s hope we’ve not degenerated to that point yet. I would not care to admit with Dr. Malcolm in the trailer for Dominion that “we not only lack dominion over nature; we’re subordinate to it.” But it’s worth considering whether this line foreshadows the chilling end to the story of our modern world of science, industry, and technology. A free and virtuous society is one thing; a techno-utopia is quite another. The difference lies in how we view our relationship to nature, both “out there” and “in here.”

So what does a right relationship with nature look like? Here we receive some guidance from revelation:

And God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.” (Genesis 1:28)

The words “subdue” and “dominion” indicate the primacy and authority humanity lawfully enjoys as creatures made in God’s image and the high point of the created world. However, lest we think there are no limits to our rule over nature, Genesis 3 speaks of a dichotomy between fallen man and his natural environs:

And to Adam he said…“Cursed is the ground because of you; in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life; thorns and thistles it shall bring forth to you; and you shall eat the plants of the field. In the sweat of your face you shall eat bread till you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken; you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” (Genesis 3:17–19)

Holding these two passages in tension, we see that while humans have indeed been given the highest seat in the hierarchy of the material world, we’re still very much a part of that world, made of the same stuff and intimately connected to it. Moreover, when we sin and fail to live within the moral limits set by our Creator, our relationship to the natural realm becomes disordered and contentious.

What is the solution? A third passage from Scripture can help orient us to a proper attitude toward the created world:

Can you lift up your voice to the clouds,

that a flood of waters may cover you?

Can you send forth lightnings, that they may go

and say to you, “Here we are”?

Who has put wisdom in the clouds,

or given understanding to the mists?

Who can number the clouds by wisdom?

Or who can tilt the waterskins of the heavens,

when the dust runs into a mass

and the clods cleave fast together? (Job 38:34–38)

This passage from Job highlights the fact that, no matter how much power we think we have or desire to have over nature, God is ultimately in control. Francis Bacon or the Jurassic Park creators may grasp after numbering clouds or rupturing heaven’s waterskins, but their machinations will be fruitless and even harmful to humanity without a key factor: wonder.

Wiker points to wonder as the attribute that allows us to live in a harmonious relationship with God, his creation, and ourselves. Wonder involves a humility in acknowledging and marveling at God’s superiority over nature (both “out there” and “in here”), even while rejoicing in the share of authority he has given to us. Wonder, paired with an entrepreneurial spirit, forms the essential character of good stewardship.

And it is stewardship to which we are called. The error in Bacon’s vision and that of the fictional dinosaur scientists lay in their failure to ask the fundamental question that Wiker poses: “Can human beings be trusted with ever more god-like power?” The answer, quite frankly, is no—unless they submit to the authority of God and the limits of the natural law. To quote Lewis again, “I am very doubtful whether history shows us one example of a man who, having stepped outside traditional morality and attained power, has used that power benevolently.” Yet, if we embrace our place in the universe as simultaneously ruler of creation, dust of the earth, and servant of the Most High, our nature “in here” will function much more seamlessly with the nature “out there.”

To this end, Wiker expresses his hope that “as stewards, rather than tyrants, we can then take care of nature and human nature as if both were great gifts for which we owe the deepest gratitude.”

If we could live more like that, I think Dr. Ian Malcolm would be proud.