“I broke sharply with all questions of religion,” said Vladimir Lenin, with typical vituperation. “I took off my cross and threw it in the rubbish bin.”

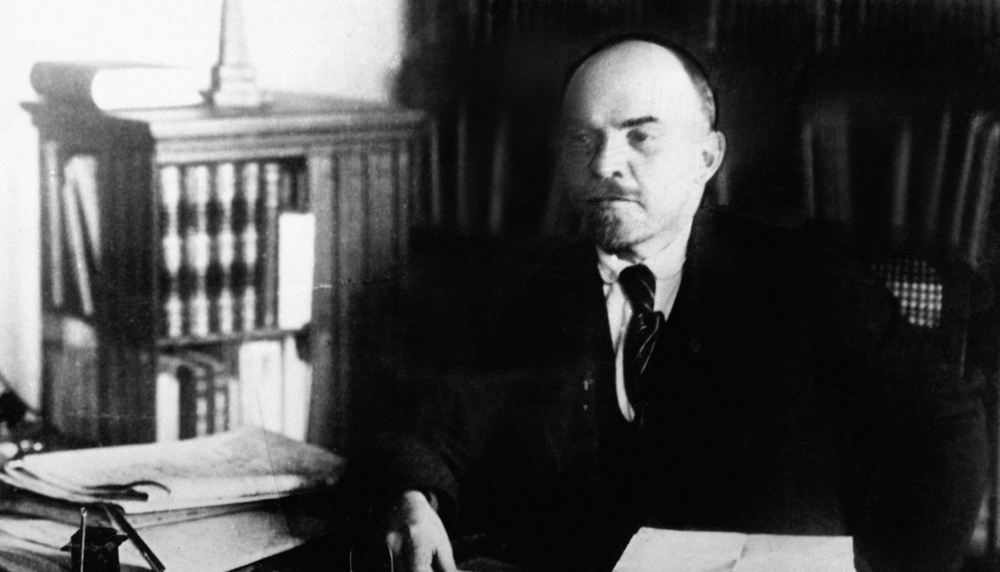

Such was a metaphor for the dark turn made by Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, who came to be known by an alias, “Lenin.” He was born April 22, 1870, in Simbirsk, a town on the Volga River east of Moscow. His parents were decent, civil people. His father, Ilya, was a pious and even a conservative man. He died of a brain hemorrhage in January 1886, when his son was only 15 years old.

The second major loss in Lenin’s life, just one year after his father’s death, was the execution by hanging of his politically radical brother, Alexander. Alexander was a revolutionary terrorist and political agitator who played a central role (as a bombmaker) in a plot to assassinate the czar of Russia, Alexander II. Most of the conspirators were pardoned, but not Alexander, given his unique role as leader. Alexander’s execution is often cited by Lenin defenders as a reason for Lenin’s turn to hard-left revolutionary. In fact, Lenin was already a left-wing revolutionary.

After a complicated upbringing, Lenin emerged a devoted disciple of the teachings of Karl Marx, from Marx’s views on property to Marx’s hatred and ridicule of religion. “There’s nothing more abominable than religion,” Lenin growled to Maxim Gorky. “All worship of a divinity is a necrophilia. … Any religious idea, any idea of any god at all, any flirtation even with a god, is the most inexpressible foulness.”

In this detestation of religion, Lenin and Marx were soulmates. Lenin quoted his ideological idol: “Religion is opium for the people. Religion is a sort of spiritual booze.” He repeated the Marx mantra often, noting on another occasion: “Religion is the opium of the people—this dictum by Marx is the cornerstone of the whole Marxist outlook on religion.”

It is indeed. Thus, insisted Lenin, “Everyone must be absolutely free to … be an atheist, which every socialist is, as a rule.”

Lenin applied that rule to his Bolsheviks, who came into being in 1903. It was at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party, beginning in Brussels and ending in London, traversing a period of three weeks from July to August 1903, that Lenin changed the name of his and Trotsky’s and Stalin’s party from the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party to what would eventually become the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It was there that Lenin and his cadre became the Bolsheviks (splitting ultimately into Bolsheviks and Mensheviks).

Lenin wasted no time in organizing his boys against religion. He declared what Mikhail Gorbachev would later describe as a “wholesale war on religion.” In 1905, Lenin said of his Bolsheviks: “We founded our association, the Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party, precisely for such a struggle against every religious bamboozling of the workers.” Society must be “cleansed of medieval mildew” and the “religious humbugging of mankind.”

As for today’s democratic socialists and Religious Left social democrats who claim that socialism is chummy and happily compatible with Christianity, Lenin at length rebuked the very notion, stating in May 1909:

It is the absolute duty of Social-Democrats to make a public statement of their attitude towards religion. Social-Democracy bases its whole world-outlook on scientific socialism, i.e., Marxism. The philosophical basis of Marxism, as Marx and Engels repeatedly declared, is dialectical materialism—a materialism which is absolutely atheistic and positively hostile to all religion. … Marxism has always regarded all modern religions and churches, and each and every religious organization, as instruments of bourgeois reaction.

Marxism is materialism. As such, it is as relentlessly hostile to religion…. We must combat religion.

Socialism: The Stepping-Stone to Communism

Lenin’s arrogance extended not only to his interpretation of religion but of the secular gospel of Marxism. He judged that he alone truly understood Karl Marx. He was the self-appointed gatekeeper. The single best statement of Lenin’s interpretation of Marx and Engels is his 1917 classic, The State and Revolution, where he endeavored to explain to the world “what Marx really taught.”

A few statements stand out from that treatise as particularly important today, when few know the distinctions between communism, socialism, and “democratic socialism.” In the chapter “The Transition from Capitalism to Communism,” Lenin explained:

And this brings us to the question of the scientific distinction between socialism and communism. … What is usually called socialism was termed by Marx the “first,” or lower, phase of communist society. Insofar as the means of production becomes common property, the word “communism” is also applicable here, providing we do not forget that this is not complete communism.

There’s much ill-informed nonsense today regarding what is socialism, as leftists in Big Tech and elsewhere try to redefine and repackage the term. But according to Marxist-Leninist theory, it’s simple: Socialism leads to communism. As Lenin noted, Marx judged “socialism” the crucial final step on the road to communism. Socialism was a prior stage to communism, a necessary but only temporary stage on the way to complete communism.

To get to that point, according to Marx and Lenin, the state itself must “wither away.” And yet, Vladimir and friends did not have much patience for any “lengthy process” of withering away. To get there, there would need to be a dictatorship. After all, Marx and Engels openly acknowledged in the Manifesto that “of course, in the beginning, despotic inroads would be necessary” to implement their plan.

Of course. People would never voluntarily submit to the draconian demands of the communist program.

In 1902, Lenin published a revealing work titled, “What Is to Be Done?” There he called for a vanguard or “party of a new type” capable of organizing and imbuing the working class with “revolutionary consciousness.” An elite cadre of educated revolutionaries was needed to inform the unwashed, ignorant Proletariat of their oppression and of their oppressors. They needed to be reeducated to know who they and their class were, who their oppressor class was, and why they needed to rise up. Every Marxist since, whether toiling in culture/gender theory or critical race theory, has picked up that same task of “consciousness raising” of the oppressed group.

Lenin the Democrat

To modern eyes and ears, a surprising aspect of Leninism was his advocacy of what he called “democracy,” which is actually not terribly different from how the modern left defines democracy. They don’t mean it in the way most people do.

Lenin used it as a vague metaphor for “equality,” which according to his lights was a form of class-based economic-wealth equality, whereas American leftists wield the term with reckless abandon to all sorts of newly birthed forms of “equality”: from income equality to transgender equality, climate equality, “marriage equality,” and whatever other social-cultural nostrums they are cooking up to fundamentally transform the country.

Lenin wrote plainly: “Democracy means equality.”

And yet, for Lenin, democracy had its limits. It was merely a means to an end: “Democracy is of enormous importance to the working class in its struggle against the capitalists for its emancipation,” said Lenin. “But democracy is by no means a boundary not to be overstepped; it is only one of the stages on the road from feudalism to capitalism, and from capitalism to communism.”

Very similarly, when leftists in the United States today invoke the necessity of free speech (while also demanding “speech codes” against speech that contradicts their ideological narratives) and extol words like “diversity” and “tolerance” (while not tolerating diverse opinions they reject), they are acting in the spirit of how Lenin saw “democracy”—as a Trojan horse for wider transformational objectives for the culture.

Lenin had spoken of democracy and even of a popularly elected assembly, but that was quickly dispatched to the ash heap of history. Like every communist since, he quickly learned that the populace does not freely elect communist majorities.

Lenin and the Birth of Identity Politics

Russia and the world would soon learn that Lenin and his Bolsheviks did not believe in the rights that the West and American Founders affirmed as natural and God-given. Within the first 10 weeks after the launching of their revolution in Russia, in late October 1917, the Bolsheviks were already abolishing all sorts of rights—from free speech to assembly and newspapers, from religious education to religious practices, from fur coats to bank credit, and much more. Lenin did this through a series of about a dozen extraordinary decrees. By the end of 1917, a fury of nationalization, centralization, collectivization, mass monopoly on communication, terror, and the abolition of property and the most basic human rights was well underway.

It is a common misperception, long perpetuated in universities, that if Lenin had not died a premature death in January 1924, thus paving the way for Joseph Stalin to succeed him, the bloodshed and tyranny that consumed Russia would never have happened. The USSR would have been kinder and gentler. Known as the “good Lenin, bad Stalin” myth, this is fundamentally erroneous. Stalin did not pervert some sublime Leninist ideology. In truth, Lenin created the Soviet totalitarian system, from the banishing of basic freedoms to the creation of the concentration camps that would become known as the infamous Gulag system.

W. H. Chamberlain, the journalist who became probably the first historian of the Russian Revolution, said that by 1920 Lenin’s secret police, the Cheka, had already carried out 50,000 executions. By 1918–19, the Cheka was averaging 1,000 executions per month for political offenses alone, without trial. Historian Robert Conquest, drawing exclusively on Soviet sources, tallies 200,000 executions at the hands of the Bolsheviks under Lenin from 1917 to 1923, and 500,000 when combining deaths from execution, imprisonment, and insurrection.

Across the board, the leading Bolsheviks from the start preached the necessity of “mass terror,” from Lenin himself to the pages of Pravda and Izvestia. All this was prior to the bloodthirsty Stalin. Lenin produced bloodcurdling directives ordering various groups and peoples, from kulaks and priests to other “harmful insects,” to be hung or shot.

He especially reviled the kulaks, the better-off peasants who resisted the regime’s theft and forced confiscation and collectivization of land and farms. Lenin asserted:

The kulaks are the most beastly, the coarsest, the most savage exploiters. … These bloodsuckers have waxed rich during the war on the people’s want. … These spiders have grown fat at the expense of peasants. … These leeches have drunk the blood of toilers. … These vampires have gathered and continue to gather in their hands the lands of the landlords. … Merciless war against these kulaks! Death to them.

The essence of Lenin’s early “Red Terror” was described by Martin “M. Y.” Latsis, a ferocious man whom Lenin appointed as chief of his killing machine. With deadly candor, Latsis affirmed that the Bolsheviks were in the process of “exterminating” full classes of human beings:

We are exterminating the bourgeoisie as a class. In your investigations don’t look for documents and pieces of evidence about what the defendant has done, whether in deed or in speaking or acting against Soviet authority. The first question you should ask him is what class he comes from, what are his roots, his education, his training, and his occupation. These questions define the fate of the accused.

This was identity politics to its extreme. Each person was hammered into a specific identity based on economics and class. Your class defined you as either oppressed or oppressor. You were stereotyped, shoehorned into an identity, and treated accordingly not as an individual but as a member of a group. Modern communists and critical theorists do the same based on other types of identity, from gender to race, albeit (mercifully) without Lenin’s violence.

For Lenin, this was “communist ethics.”

As he explained in an October 1920 speech to the Russian Young Communist League: “Is there such a thing as communist ethics? Is there such a thing as communist morality? Of course, there is. … We reject any morality based on extra-human and extra-class concepts.” He added: “We do not believe in an eternal morality. … Communist morality is based on the struggle for the consolidation and completion of communism.”

This, of course, is pure moral relativism. For Lenin, it was the basis of communism. It became the pretext for the Marxist-Leninist society’s system of slaughter.

Vladimir Lenin’s revolution was underway. Only death would stop him, but not it. When death knocked on Lenin’s door in 1924, Joseph Stalin was ready to succeed him. The entire system was already built and awaiting him.

What is Lenin’s legacy? It is death, dictatorship, and hate. To Vladimir Lenin, individuals are not made in the imago Dei. They are defined not as children of God but as members of groups. Your group identity defined you, sometimes to the point of physical liquidation. That is an ugly legacy for humanity.