Long after we’ve all passed on, how will future generations remember us?

One answer: books.

Certainly there will be landmarks and buildings and other memorabilia that help our descendants understand our society as it exists today, along with the people who helped shape it.

But there has been no better record keeper and preserver of facts than well-preserved writings.

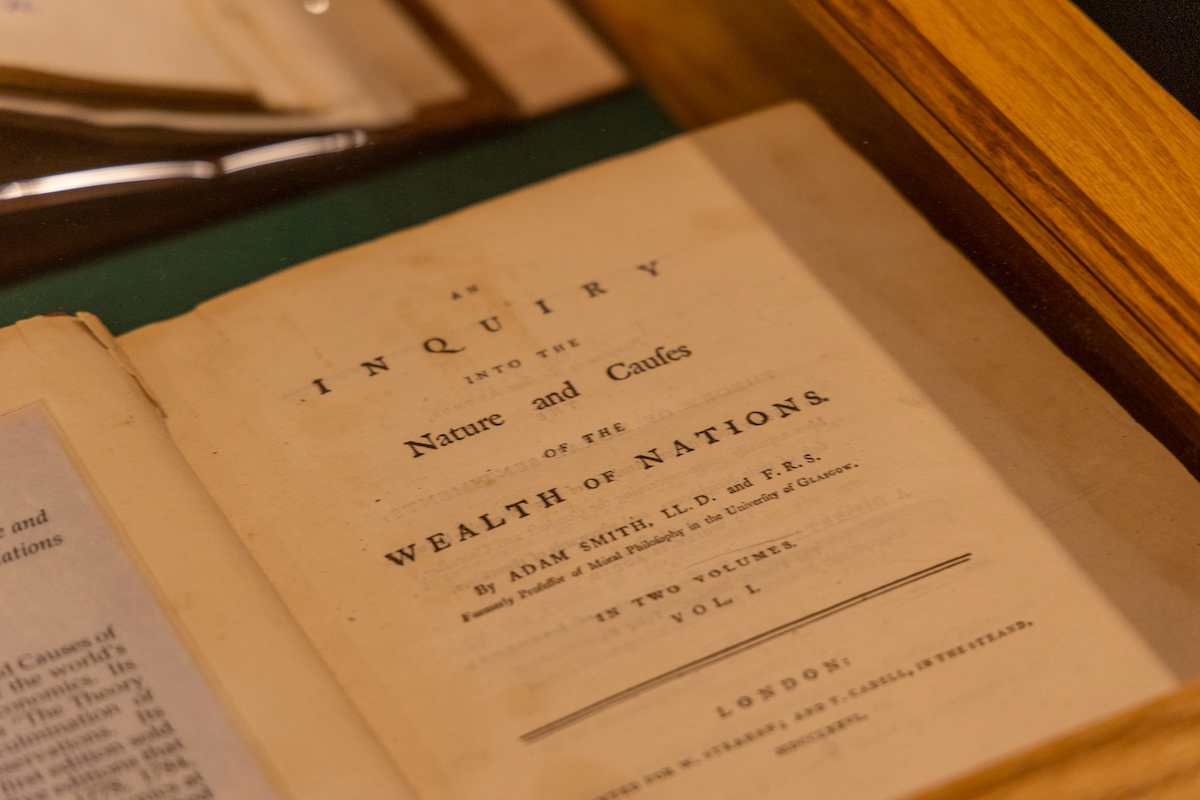

It’s why The Remnant Trust is committed to preserving and sharing important literature, and why we’re bringing a collection of works from the finest thinkers over the centuries to Michigan. Since Sept. 23, the public has been able to explore first editions of works by Frederick Douglass, as well as The Federalist Papers and the first public printing of the Emancipation Proclamation, among other great works.

The notion that there is power in ideas is an old one. The cliché that, “Knowledge is power,” has been traced to the late 17th-century writings of the philosopher Sir Francis Bacon.

The 19th-century historian Lord Acton believed that ideas themselves were the motive force in history, saying: “The history of institutions is often a history of deception and illusions; for their virtue depends on the ideas that produce and on the spirit that preserves them, and the form may remain unaltered when the substance has passed away.”

Given Acton’s sentiments, it’s only fitting that the great books on display are hosted at his namesake, the Acton Institute.

Why does preserving books and other great works matter so deeply?

Because from the insights, observations and obscurities of history’s great philosophers and historians, we see the roots of the common understanding of the importance of education and literacy to human development, flourishing social institutions and a vibrant engagement with government.

Ideas of individual liberty and the dignity of the human person are at the heart of any truly advanced civilization.

These ideas are complex, and although much of our social life is mediated through the bonds of family, church, community and citizenship, this is a dynamic process. A fixed tradition is also needed to faithfully transmit the legacy of civilization to our posterity.

Literature serves this purpose. It is the place we may turn when times are troubled and there is a need to reaffirm our commitments to human liberty and dignity by returning to their greatest proponents and most articulate expositors.

The written ideas of those who preceded us can also serve to renew our understanding of the nature and character of the American project. As the founding of our nation continues to come under fire from all different directions, we can look back to the words of James Madison in The Federalist Papers (a 1788 first edition on display in the Remnant Trust collection) to remember why our system of divided power, checks and balances, was devised:

“It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

In doing so, we can become reinvigorated in our appreciation for our national inheritance. When we read that “we hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal” in the Declaration of Independence, we may know that few among us are the direct biological descendants of those who wrote those words and signed their names to that document.

But we can, as Abraham Lincoln said in the “electric cord” speech in 1858, read them and know that we “have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, and so they are.”

The written word serves as a landmark set by our forefathers. Being in the presence of books both old and rare has a way of making us look at them with fresh eyes. We see the way ideas have entered the world in the same way we have — embodied — and the degree to which they shape our history and illuminate our minds is the degree to which we take them into our hands and our thoughts.

The poet T.S. Eliot wrote, “Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?”

Answer: It’s in the books from which we have become estranged.

This article originally appeared in The Detroit News on Oct. 4, 2021