The decline of civil society has become a running theme of social and political commentary, marked by disruptions in marriage and family, diminishing church attendance, and the dilution of social capital. Wherever one looks, community life seems to be fading. Why?

It’s a question that’s been explored at length, whether in popular works like Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone and Charles Murray’s Coming Apart or through research initiatives like the Social Capital Project, which seeks to map the geography of community life across America.

In a new report from the American Enterprise Institute, researcher Lyman Stone digs deeper still, examining the varied history of American civil society in all of its particularity. From the founding to the frontier to industrialization, how has American community evolved over time?

For many, the topic can quickly tend toward reminiscing about America’s storied civic past. Yet Stone challenges our popular assumptions, pressing us to learn the facts about early American life and reflect on the unique value and nature of each association and institution we embody and embrace.

“Tracing the history of associational life from America’s founding reveals that not all associations are created equal,” Stone explains. “Some popular associations provide undeniably positive benefits for their participants and society (such as churches or labor unions), while others have proven deeply destructive (such as the Ku Klux Klan) …Thus, the link between associational life and social capital is complicated.”

Stone begins by enriching our common ideal of “associational life” in America, which stretches back to Alexis de Tocqueville’s observations during his famed 1830 visit to the U.S.

“Americans of all ages, all conditions, all minds constantly unite,” Tocqueville wrote. “Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but they also have a thousand other kinds: religious, moral, grave, futile, very general and very particular, immense and very small; Americans use associations to give fêtes, to found seminaries, to build inns, to raise churches, to distribute books, to send missionaries to the antipodes; in this manner they create hospitals, prisons, schools.”

It’s a beautiful picture of bottom-up cooperation and entrepreneurial spirit, but much has also changed. Whereas Tocqueville praised businesses, churches, schools, and even governmental institutions, much of our modern analysis (such as Putnam’s) measures civil society against 20th Century fraternal organizations, such as clubs, charities, and sports teams. Which leads to Stone’s primary question: Given the diversity and evolving nature of American institutions, what types of associations have actually served to build social capital and promote human flourishing across civil society?

To find an answer, Stone assesses a range of associations and institutions, weighing the pros and cons of each, as well as their prominence in modern American life. His conclusion? Americans have steadily replaced intimate relationships and more publicly minded social institutions with “games and spectacles” — “bread and circuses.”

“Today, Americans tend to have fewer ties of association with each other and fewer organizational memberships, but they also spend less time on friendships,” Stone writes. “Many of the ties to social identity Americans do have are less conducive to social flourishing. For example, church attendance has fallen dramatically despite its social benefits, whereas entertainment-focused associations such as sports teams have risen in popularity.”

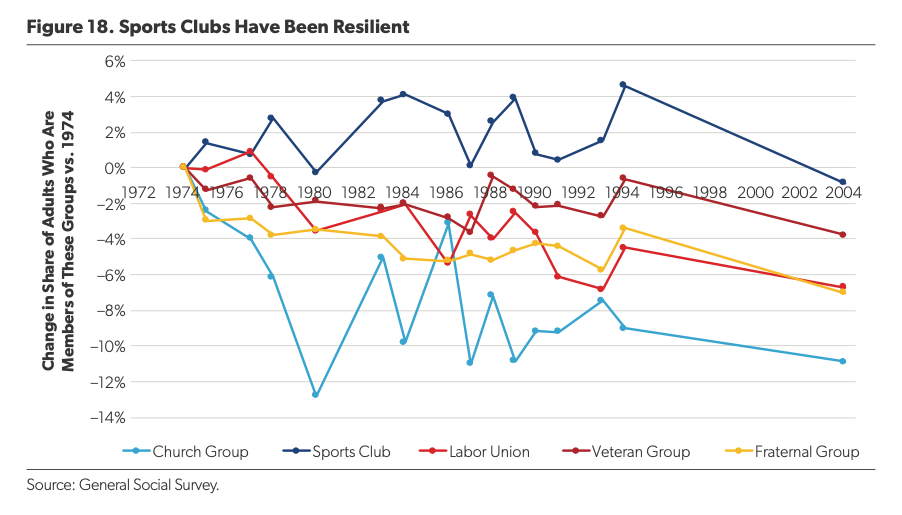

When it comes to sports, specifically, America has seen a rise in activity across the board, from youth participation and community involvement to an increasing investment in major league sports. As shown in the following figure, amid declining participation in churches, unions, and other fraternal clubs, sports have largely stayed steady.

Some will say this is a positive development, arguing that sports can serve as a productive means for character-building and community togetherness. According to Stone, however, “the relationship between sports and social capital is complicated,” and “while being a member of a sports club probably does help build social capital, it is far less effective than almost any other form of associational life.”

Indeed, while sports have traditionally shown promise in stirring up patriotism and national unity, in our current context, they routinely serve as a platform for some of our most intensive culture-war debates (who can play, how we play, how/whether we salute, etc.). Likewise, in lacking an intensive focus on solving individual or community problems, the emphasis on entertainment and zero-sum combative struggle quickly outpaces other values.

For these reasons and more, Stone perceives a connection between the boom of American “bread and circuses” and the simultaneous rise of the administrative state.

“This focus on sports is flatly contrary to the vision of republican citizenship articulated by many of the Founding Fathers, who had inherited a critique of ‘games’ from Christian and classical thinkers of the past,” Stone writes. “That the rise in sports culture has coincided with a weakening in other forms of social capital and an expansion of the state is suggestive as well. Sports may be more about the government’s desire to direct public sentiment toward trivialities than building effective associations that are useful for society.”

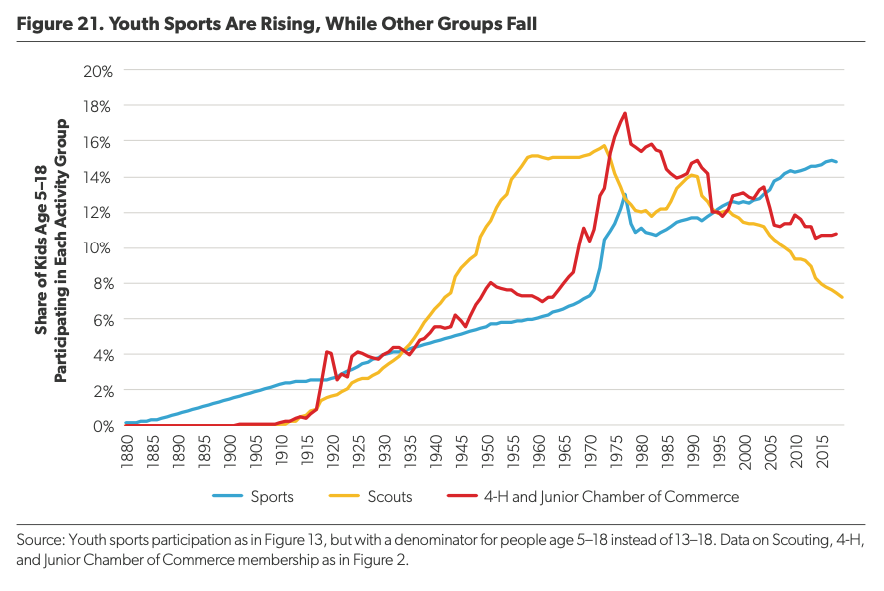

Obviously, this is not to say that sports are bad or don’t belong in a free society. But when they serve as the only outlet for community interaction — or when we exchange boys’ soccer for Boy Scouts — we shouldn’t pretend that this is an equal trade.

“To the extent sports compete with other forms of personal entertainment, this is no knock against them,” Stone writes. “But to the extent that sports compete with other, possibly very socially beneficial activities, this lack of wider social benefit could be worrisome.”

Stone then turns his attention to the expanding reach of public schooling, from elementary to college, which happens to coincide with our increased focus on entertainment-oriented extracurriculars. Even as school activities increasingly consume the lives of America’s rising generations, the range of formative, outward-oriented school clubs and associations is apparently shrinking, once again replaced by sports and other diversions.

“ As schools have claimed a growing share of American children’s lives, those activities most closely connected to school-based identity have correspondingly grown in popularity, while activities that could connect children across school lines have suffered,” he explains. “Bonding capital inside a school community is perhaps enhanced… but bridging capital beyond it is incontrovertibly lost.”

Here, too, Stone emphasizes that we ought to stay attentive to the values at play with each and every institution and endeavor. As civil society shifts and evolves, to what extent are we promoting “low-stakes,” entertainment-oriented activities at the expense of other formative, integrative, and outward-oriented associations?

“American associational life has changed many times in its history and taken on new and different forms. These different kinds of associations met different social needs and created different benefits and costs for wider society. But in the long run, organized public associations with some clear positive aim are a benefit to society, whatever their form.

“Thus, the decline in the density of these associations, and especially their replacement by narrower ideological organizations or broad, low-stakes associations such as sports, may create new difficulties for American society. The extent of this decline has been somewhat overstated in prior research but is nonetheless real and closely tied to a decline in community orientation.”

Though it may seem like a tame solution, mere attentiveness is a solid start when it comes to problems of plenty. “Most of the change in associational life can be attributed to essentially one factor: technological improvements leading to a higher standard of living,” Stone explains. “A wealthier society provides more benefits via the state instead of private organizations, even as the invention of radio and television displaced many traditional information networks … This history cannot be undone.”

Certain policies, such as expanded school choice, can certainly help to loosen up the system and add more diversity to associational life across our institutions. But in the end, it will still come down to our values and priorities as individuals, families, and communities.

The void is apparent, but the solution is not prone to quick-and-easy policy grabs or coercive social engineering. Reviving our communities will require a renewed focus on what truly matters, as well as corresponding renewal and bottom-up cultural witness across all spheres of society.

“The future of associational life in America will depend on what Americans really want,” Stone concludes. “If they want modern bread and circuses, they will get it. Rebuilding lost associational life will require a critical mass of Americans to make costly personal choices to reinvest in their communities and relationships.”