Proposals for “economic stimulus”, the use of monetary or fiscal policy to stimulate the economy, have become a permanent fixture of our politics.

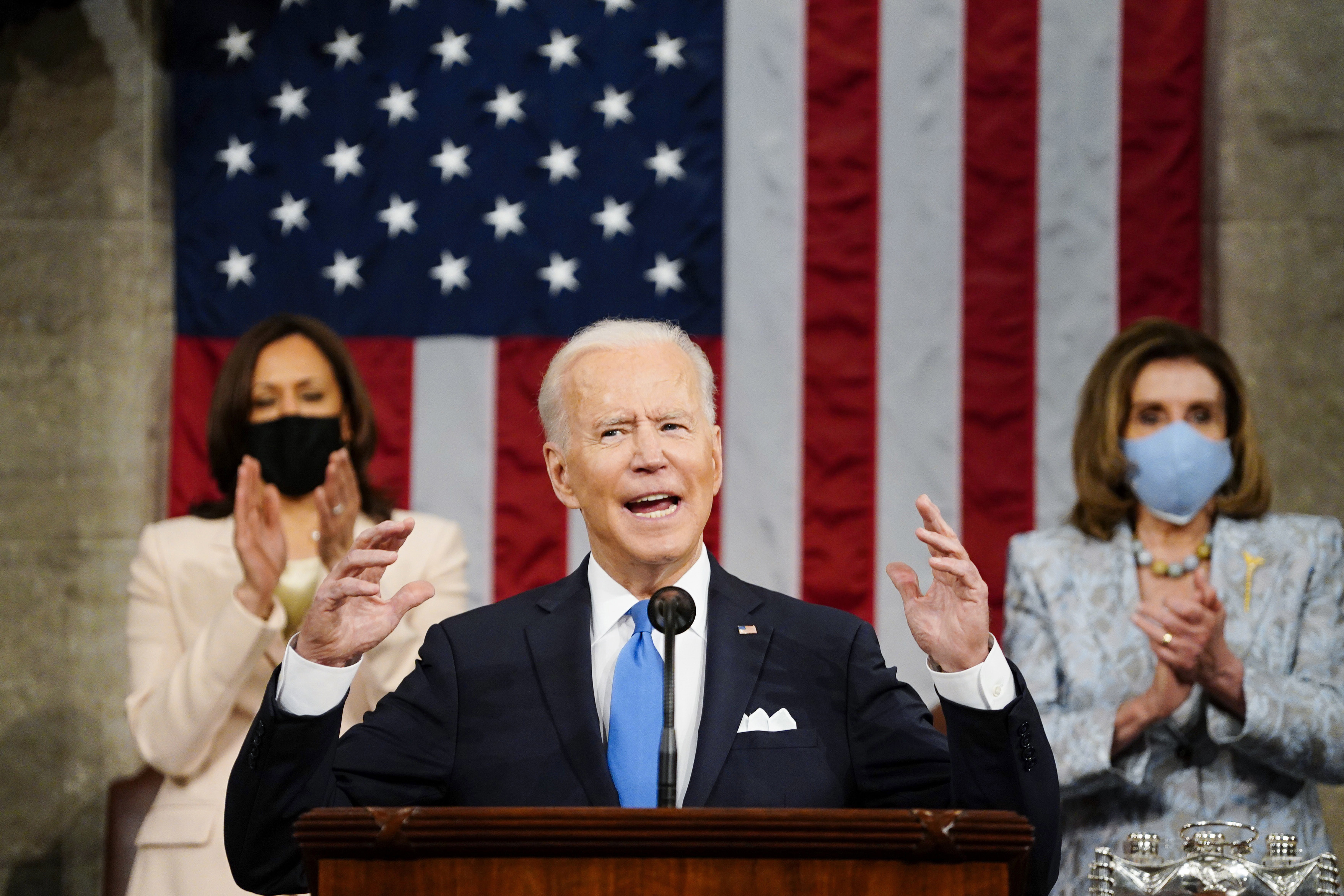

President Joe Biden recently proposed $1.8 trillion dollars in additional “economic stimulus” in the form of the American Families Plan. This represents an extension of the unprecedented wave of government spending and proposed spending which began last year in March by the Trump administration with the CARES Act ($2.2 trillion) and continued this March with the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan ($1.9 trillion). Along with the proposed American Jobs Plan ($2.2 trillion) the grand total of this spending and proposed spending is represents over a third of the size of the entire economy of the United States.

As originally envisioned by the economist John Maynard Keynes the logic of “stimulus” was for government to provoke a “response” in the private sector through fiscal and monetary policy that would raise aggregate demand for all goods and services during recessions where there was a danger that the economy would not self-correct. Keynes posited that if not for stimulus spending on the part of government, high unemployment, decreased productivity, and patterns of lower growth may otherwise persist.

This was the logic behind the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008 ($152 billion), Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 ($700 billion), and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 ($831 billion) in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-2008.

What is curious about this latest round of stimulus initiatives, aside from their enormous size, is that fact that they do not fit the traditional countercyclical model of “economic stimulus.” The International Monetary Fund currently projects economic growth in the United States to be 5.1% in 2021 and 2.5% in 2022. The United States is also currently facing a labor shortage, soaring commodity prices, and a bull market in stocks.

Our political class, on a bipartisan basis, has adapted the Keynesian language of stimulus for a pattern of an easy and unjust fiscal policy and unsustainable deficit spending detached from our actual economic circumstances. This rhetorical sleight of hand was made transparent by Biden’s proposed increase in the top rate of the capital gains tax from 20% to 39.6%. Such a policy disincentives private-sector investment and would raise significantly less revenue than promised. What then is the actual motivation behind such proposals if not “stimulus”?

Niall Ferguson, Milbank Family Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, makes a compelling case in an essay in the latest issue of The Spectator, “The China model: why is the West imitating Beijing,” that what is actually being pursued is a policy of central planning modeled on the supposed success of the Chinese model:

In late March, for example, Joe Biden proposed to Boris Johnson a western version of China’s One Belt One Road initiative. ‘I suggested we should have, essentially, a similar initiative, pulling from the democratic states, helping those communities around the world that, in fact, need help,’ Biden told reporters after the call. Conventionally, ‘OBOR’ (also known as the Belt and Road Initiative) is described as a vast infrastructure investment programme, though a vast propaganda and dodgy loan programme might be more accurate.

No one has had quite the temerity to suggest that Biden’s domestic spending programme is also somewhat Chinese in conception as well as in scale. It began with the $1.9 trillion Covid relief bill (the American Rescue Plan). Then came the $2.2 trillion infrastructure bill (the American Jobs Plan). And just last week we were presented with the $1.8 trillion American Families Plan. Plan, plan, plan — if only J.K. Galbraith were still here to see his theory vindicated.

The combined price tag for all these plans comes to just under $6 trillion, equivalent to more than a quarter of US economic output (though the spending on both the Jobs and Families plans is spread over multiple years). Republicans are not well positioned to criticise, having inadvertently legitimised both universal basic income and Modern Monetary Theory with the emergency measures they passed last year. It has been left to former Democratic officials, notably Larry Summers and Steve Rattner, to express disquiet at the scale of the fiscal expansion, which not only risks overheating an already recovering economy, but also permanently increases the role of federal government in the economy.

While China’s rapid economic development over the past thirty years has been impressive it was fueled by market liberalization away from state ownership and central planning. Recent trends in China under the leadership of Xi Jinping have increased control over both state-owned and private enterprise leading to a fiscal situation that former finance minister Lou Jiwei ha characterized as “extremely severe with risks and challenges.”

Ferguson rightly warns, “It is one thing to compete with China. I firmly believe we need to do that in every domain, from artificial intelligence to Covid vaccines. But the minute we start copying China, we are on the path to perdition.”

The first step to counter movements toward more centralization and control over the economy is to call those measures by their name and reject the framing of these issues as “stimulus.” Jesus admonishes us that, “All you need to say is simply ‘Yes’ or ‘No’; anything else comes from the evil one.” (Matt 5:37)

Serious issues such as government spending must be debated openly and honestly. That can’t happen if our leadership misleads the public by obfuscating the true nature of their proposals.