Everyone knows that there is a difference between knowing about something and knowing how to do something. The first is a superficial way of knowing, not a bad way to begin, but it is no substitute for the mastery which comes by integrating knowledge into experience. It is the difference between a dilettante and a true student, which is the same as the difference between a bad and a good teacher. The dilettante teacher is the punchline of the old joke, “Those who can’t do teach, and those who can’t teach teach gym.” It is these sorts of teachers that Paul warns Timothy about saying:

But the aim of our instruction is love that comes from a pure heart, a good conscience, and a sincere faith. Some have strayed from these and turned away to empty discussion. They want to be teachers of the law, but they do not understand what they are saying or the things they insist on so confidently. (1 Timothy 1:5-7)

Last week I shared a concise natural law reading list. Natural law is a topic in the discipline of philosophy. The list was designed to teach you that concept by walking you through the philosophy underlying it and by showing you how thinkers of the past and present have used that concept to think about a range of issues in law, politics, and culture. This list is designed to help you learn the economic way of thinking and in so doing become your own economist.

Many books try to do too much. They are so comprehensive the reader winds up with knowledge which is a mile wide but only an inch deep. They become dilettantes about a staggering array of topics instead of becoming students of a discipline. Henry Hazlitt’s Economics In One Lesson is the exact opposite type of book. It teaches only one lesson but it teaches it so well that it reshapes the way you understand everything. It is a lesson in attention, a lesson in, “looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy [and] tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.” Hazlitt then methodically and clearly applies the lesson to a myriad of topics unfolding the implications of the lesson and unraveling all it can teach us. It teaches us that that which is unseen has even more to teach us than that which is seen.

Grounded in the one lesson it is now time to be introduced to others. Paul Heyne’s short survey, A Students Guide to Economics, is a remarkable book. It is a survey of major topics in economics as an analysis of the questions which gave birth to their study. It introduces you to the major figures in economics who asked these questions, the influential works in which they asked and attempted to answer them, and gives you the historical context of why these questions came to them in the first place. It is an apprenticeship at the feet of the masters of the economic way of thinking.

With feet planted firmly in the past we can now step boldly into the present and leap into the future. Heyne, Boettke, and Prychitko’s book, The Economic Way of Thinking, is like most textbooks in one very good and one very bad way. Like most textbooks it is very good at teaching you the specific language and vocabulary of modern economics (i.e. elasticity, efficiency, externalities, etc.). Also like most textbooks it is, in a bad way, very expensive (Pro-tip: earlier editions are vastly more affordable). The Economic Way of Thinking is unlike most textbooks in two truly excellent ways. First, it is eminently readable. Second, the questions at the end of chapters are truly remarkable:

Which of the following actions generate negative externalities that also create social problems?

a) Tossing peanut shells on the sidewalk

b) Tossing peanut shells on the floor at a major league baseball game

c) Dropping a candy wrapper on the sidewalk

d) Dropping confetti from an office building during a downtown parade

e) Setting off load firecrackers on Independence Day

f) Producing a fireworks display on Independence Day

These questions are not invitations to flip back to the prior chapter to find the answer but invitations to inquiry using the concepts taught in prior chapters. Springboards to becoming an economist.

Happy reading!

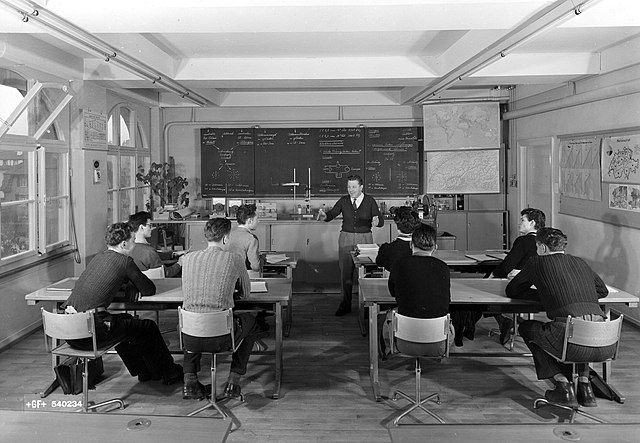

Image Credit: Werkschule, lessons in economics. CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication