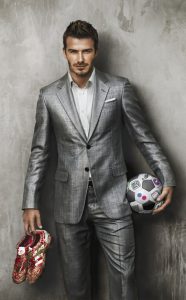

Retired soccer legend David Beckham was denied knighthood in 2013 after British authorities flagged him for “tax avoidance,” according to a new story in the Telegraph. Beckham had invested in Ingenious Media, a company that supported the British film industry – and also allowed investors to write off their losses. Officials at the company say its model provided wealthy people like Beckham the opportunity to reduce their tax liability while following existing tax law; the case is still being thrashed out in the courts.

Beckham’s saga joins those of numerous Premier League soccer players who have been denigrated in the media for using indisputably legal means to maximize their net income. Strange as it is to American ears, even the conservative-leaning Daily Mail reported in shock that their tax avoidance methods were “all legal.”

That raises an important moral question: For generations, economic leftists have campaigned on a promise to “soak the rich.” But do the rich have a moral obligation to be “soaked?

Richard Teather, a senior lecturer in tax law at Bournemouth University and a fellow at the Adam Smith Institute, addresses that question in an essay published today in Religion and Liberty Transatlantic.

“Is it immoral to take advantage of an opportunity offered to us by the government?” he asks. “It is difficult to see why.” The law’s only moral precept is that it be kept.

Significantly, the tax code’s intertwining layers of Byzantine calculations and labyrinthine exemptions did not come about by following any defined moral code. As in the United States, cronyism influenced its haphazard and often conflicting development:

The tax system is highly complex, because of deliberate decisions by the government over decades. … With all these variables, it is impossible to say that there is any general obligation to pay a certain amount of tax. The tax system is entirely a creation of statute; a system based on general morality could not have come up with anything like its complexities, variations and exemptions.

Foisting a moral burden of paying maximum taxation, regardless of the relief explicitly provided by the law, is particularly troublesome in the case of professional athletes and others who have only a few years to earn peak salaries:

By looking at annual rather than lifetime income, the tax system can be unfair to people with erratic or variable income. Top footballers will pay the top 45 percent tax, but most will only earn at that level for a few years. If their income were averaged over an ordinary working life, many would be in a lower bracket.

The average professional football (soccer) career lasts eight years, according to an analysis from The Guardian.

One should ask if the same issue applies in the United States, not merely to sports stars, but to those who climb the ladder of success. Taxing “the rich” means taxing changing groups of people experiencing different stages of life. Nearly two-thirds of people born into the lowest income bracket will leave that position over the course of their lifetimes. In all, “28 percent of the children of parents in the top quintile of the residual wealth distribution will end up in the bottom two quintiles, and 28 percent of the children of parents in the bottom quintile of the residual wealth distribution will end up in the top two quintiles,” according to a report published last July by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

A progressive annual income tax cannot distinguish between Paris Hilton and Horatio Alger.

Finally, Teather raises an overlooked issue: Is giving your income to the government the best way to indulge in “charity”? He writes:

That is not to say that we can be selfish and keep our money to ourselves. What we do with our money, and our time and other talents, is an area where morality and the obligations of charity and society play an important role. But so long as we pay the amount of tax that is legally due, the best use of our remaining income is not necessarily to give it to the government.

You can read his full article here.