Whenever I read a story involving one of the profusion of holy relics preserved and exhibited over the centuries, whether it be the Shroud of Turin or the finger bone of the fifth-century patroness Saint Genevieve, to this day displayed in a small glass cylinder in the Chapel of St. Étienne-du-Mont in Paris, I hark back to my childhood experience of visiting the mummified remains of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, better known as Lenin, the centenary of whose death falls on January 21, 2024.

This was the late 1960s, when for some years my father served as the British naval attaché to Moscow. I was of middle school age at the time, and I admit it was all something of an adventure. My parents once whisperingly told me that the KGB had planted listening devices in our home and car, which I thought impossibly glamorous. One snowy afternoon in December of 1968, my father and I even found ourselves in a small group of Western visitors invited to the suburban home of the deposed Soviet dictator Nikita Khrushchev, who astonished me by speaking with authority about my childhood sporting passion of cricket. (But that’s another story.)

One day at about this same time, my parents and I were escorted to the front of an impressively long line of people assembled around one corner of Moscow’s Red Square in order to enter the pillbox-like edifice of Lenin’s Tomb. Even then I registered it as a sinister-looking place, full of dimly lit internal corridors down which visitors shuffled in silence, with the added presence of heavily armed Red Army sentries posted every few feet of the way. There was a rigidly choreographed solemnity to the whole event that included the prohibition of hats, talking, lingering, or photography. The general atmosphere was that of visiting a sacred historical crypt in a church, although there was also an ominous hint of one of those missile-filled underground lairs or dimly lit councils-of-war meetings beloved of the James Bond movie franchise, which suddenly turns bad for Bond and ends up with him in the clutches of some scarred-faced psychopath holding an albino cat on his lap.

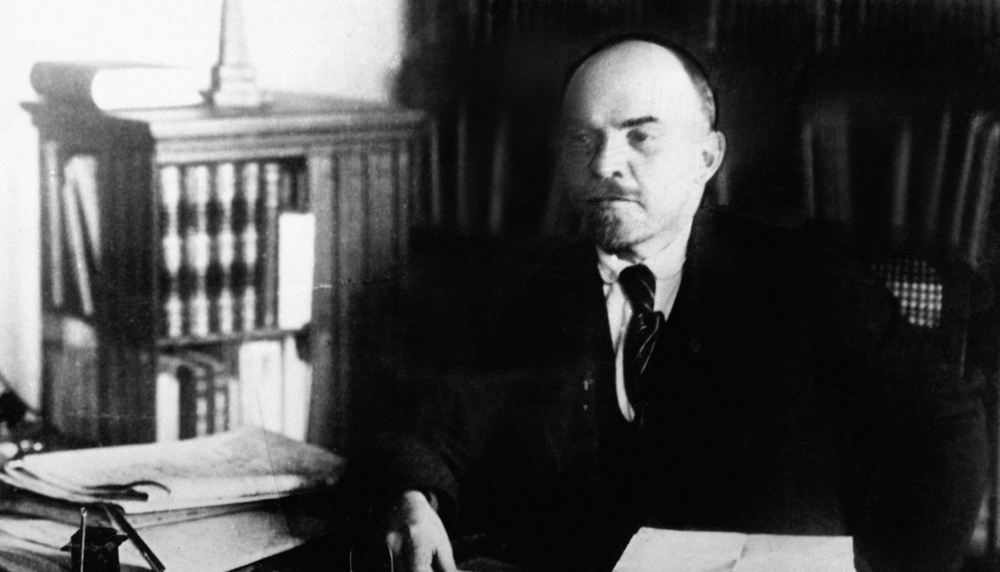

At the climax of our progress into the depths of the mausoleum, Lenin himself suddenly appeared before us. The Revolutionary Scout was lying in a glass-topped sarcophagus, his trademark goatee and mustache neatly trimmed, his eyes closed, his arms resting at his sides. Someone had dressed him in a suitably austere dark suit, a polka-dot tie, and what looked like a freshly starched white shirt. It was a bizarre sight, part spiritual epiphany, part carnival freak show. The word “waxy” was the consensus among our party to describe what was visible of the corpse, although more impressive than that was the stage management of the whole affair, with all the building’s muted lighting and sloping black granite floors, and its reverently hushed atmosphere attended by those impassive guards. A few weeks after this first visit, my parents and I returned to the scene with my maternal grandfather, who had been personally caught up in the Bolshevik Revolution while working as a volunteer for the International Red Cross some 50 years earlier. After emerging from the tomb into the harsh winter sunlight of Red Square, he commented of the experience: “On the whole, I prefer to see Lenin this way rather than when he was alive.

All of which raises the question: What explains the continuing fascination with the man whose mortal remains are still visited by 2.5 million of the curious or obsessed each year, only marginally fewer than pay to pass through the gates of the Disneyland Park in Paris, and more than those who patronize the Smithsonian? And for that matter, what accounts for the revolutionary fervor that seems to have stirred in the young Lenin at around the time of his 18th birthday, turning an intelligent but somewhat unimaginative provincial adolescent (“A young man who possesses a keen mind, but one of a single dimension,” as his friend and future colleague Viktor Chernov noted) into the messianic figure unencumbered by critical self-awareness, by doubts, or by any other moral conflict over the costs inflicted on others by the pursuit of his ideologically pristine goals?

Let’s take the transformative issue first. Lenin (as we’ll continue to call him) was born in 1870, the third child of a modestly prosperous school administrator and his schoolteacher wife who lived in Simbirisk, 400 miles east of Moscow on the river Volga. Both parents were impeccably middle-class, churchgoing, and monarchists. His father died when Lenin was 15, seemingly the trigger for his son’s behavior to become unruly and confrontational, although the real crisis point followed in May 1887, when Vladimir’s elder brother Sasha was tried and swiftly executed for his involvement in what seems to have been a somewhat half-hearted student plot to assassinate Tsar Alexander III. When the newspaper carrying the details of his brother’s death reached Lenin at the family home in Simbirsk, he threw the paper to the floor and announced:

“I’ll make them pay for this! I swear it!”

“You’ll make who pay?” asked a neighbor who had come to console Lenin’s mother.

“Never mind, I know,” he replied.

Psychologists will argue that this was the tipping point, or the accumulation of critical mass, that marks the abrupt conversion of the largely unexceptional youth into the fanatical adult, although the trauma of Sasha’s death was arguably only to give definition to a mind that observers such as Chernov agree was fully capable from a young age of rationalizing acts of appalling evil. Perhaps it’s fair to say that when a modestly privileged but emotionally troubled childhood gives way, as in Lenin’s case, to an adolescent taste for nihilistic literature and the more anarchic visions of socialist thinkers such as Mikhail Bakunin and Sergey Nechayev, and factors such as the state execution of a beloved sibling and the obvious distress of a single-parent mother are added to the mix, normal standards of self-restraint can be relaxed to the point where dramatic results follow.

It’s a curious paradox that the century-long fascination with Lenin is more pronounced today in Western academic and media circles than on the streets of Russia itself. (That’s surely a manifestation of the epidemic of national self-hatred that remains the great throughline of our intellectual class, its being the only way in which they can square their sense of superiority with their country’s position in the world.) One of Lenin’s chief appeals is that he fits squarely into the “great man” school of history. In a modern era when even infectious diseases are the subject of stultifying partisan conflict, he at least had the vision and the will to get things done. When in October 1917, Lenin, disguised in a gray wig and the costume of a Lutheran pastor, returned to Russia from his latest exile, power in that vast and troubled land was still divided in an uneasy alliance between a provisional government on the one hand and cells of ill-disciplined socialists and anarchists on the other. Without his undoubted organizational ability and fanatical belief in the cause, the national revolution might well have descended into the same administrative stasis that had overcome its precursor eight months earlier. He alone had the unflinching will and power of persuasion to carry the movement to fruition.

Set against these laudable qualities, there is of course another possible interpretation of Lenin’s gift to humanity: that of an utterly centralist and ruthlessly authoritarian approach to government that served as the blueprint for several of the world’s subsequent tyrannical monsters, from Joseph Stalin to Mao Zedong, from Robert Mugabe to Kim Jong Un, to name just a few of the many examples available, and whose malign influence is far from extinct today. Having preached the need for terror long before the revolution, Lenin was later responsible for stiffening the sinews of even the most callous of his fellow Bolsheviks when it came time to murder or mutilate the movement’s enemies on trumped-up charges forced out of them by torturers, or to have them rounded up and sent to the gulag to give the fantasies of conspiracy or bourgeois contamination some apparent credence.

Here is Lenin writing to his fellow revolutionary Grigory Zinoviev on June 26, 1918:

Only today we heard in the Central Committee that in Petrograd the workers wanted to answer the assassination of [the Bolshevik leader] Volodarsky with mass terror, and that you restrained them. I protest decisively. We compromise ourselves. This is an arch-war situation. We must work up energy and mass terror against counter-revolutionaries, and especially in Petrograd, the results of which are decisive.

Or, in broadly similar vein, Lenin’s remarks to his colleague Lev Kamenev, at the time Kamenev proposed they abolish the death penalty.

Nonsense! How can you effect a revolution without firing squads? Do you expect to dispose of your enemies by disarming yourself? What other means of repression are there? Prisons? Who attaches significance to them?

While his once-ubiquitous image has long since disappeared from the mastheads of Russian newspapers, and from the country’s banknotes and postage stamps, Lenin’s influence on the successor state to the one he brought into being in 1917 is still palpable today. Even Vladimir Putin recently sought to blame him for his nation’s attritional war in Ukraine by having unnecessarily created that entity in the first place.

“The region was entirely created by Russia, or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia,” Putin explained, by way of a rationale for his February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. “What was the point of transferring to the newly, often arbitrarily formed administrative units vast territories that had nothing to do with them?”

Putin then proceeded to answer his own question.

“There is an explanation,” he continued. “After the Revolution, the Bolsheviks’ main goal was to stay in power at all costs. They did everything for this purpose,” including satisfying “any demands and whims of the nationalists within the country.” As a result, Putin concluded, “Soviet Ukraine stems from the Bolsheviks’ policy and can be rightfully called ‘Vladimir Lenin’s Ukraine.’ He was its creator and architect.”

But perhaps Lenin’s real legacy as it applies to the West today lies in the continuing delusion that the state might properly interest itself in every aspect of our lives, down to the smallest details of how and when we forgather, travel, communicate, worship, or educate our children—surely one of the observable truths of the whole protracted COVID ordeal—a distortion of the original founding ideal largely dependent on the apathy of the majority and the existing culture’s loss of faith in itself. These factors may be glimpsed at work in the United States today just as they were in the pre-revolutionary Russian Empire of more than a century ago.

“We repudiate all morality which proceeds from supernatural ideas,” Lenin once informed an eager audience of Young Communists, in the course of denigrating organized religion as a whole and its “bourgeois” trappings in particular. Following that, he turned to matters touching on his concept of the proper exercise of central authority, and his extreme intolerance of any dissent from same.

“We further repudiate all morality which proceeds from ideas which lie outside class conceptions,” Lenin continued. “In our opinion, morality is entirely subordinate to the interests of the class war. Everything is moral which is necessary for the annihilation of the old order. Our morality consists solely of close discipline, and in conscious war against the enemy. … We do not believe in external principles of morality, and we will expose this deception.”

There, surely, speaks the true voice of the revolutionary mania that Lenin both articulated and exploited, and that did so much to pave the way to the hell of Joseph Stalin and his mimic regimes around the world up to our present day.