In 1959, when Richard Condon published his political thriller The Manchurian Candidate, he took a topical idea and ran amok with it. The idea was that during the Korean War a platoon of GIs had been captured by the Chinese, brainwashed (“not just washed, but dry-cleaned”), and released back home to do the enemy’s bidding. The troop’s leader, Raymond Shaw, happens to be an already troubled young man with a ruthless and ambitious mother (there’s the merest hint of incest in their relationship), a U.S. senator as a stepfather—and he’s a crack marksman to boot, thus qualifying him as the ne plus ultra of sleeper assassins.

Years pass, Shaw fights with his mother, has one or two unsatisfactory love affairs, suffers a series of recurring nightmares, meets up with several of his army buddies, and begins to wonder whether something untoward might have happened to them back in Korea. Meanwhile his McCarthy-esque stepfather, Johnny Iselin, maneuvers himself to his party’s vice presidential nomination at its national convention. At this point, Condon reveals the significant plot twist that Shaw’s mother has been acting all along as his communist handler. Her plan is to program her son into killing the party’s presidential candidate so that Iselin, who is in on the plot, can succeed him and do the Reds’ bidding. What follows is one of those classic sweaty-palmed, sniper-in-the-bleachers suspense climaxes beloved of Alfred Hitchcock and his many imitators. I’ll spare you the rest, except to say that it doesn’t turn out well for any of the Shaw family.

The running-amok part owes itself to Condon’s tendency to operate as a sort of literary performing flea. As well as serving as a thriller, The Manchurian Candidate incorporates elements of outright fantasy and science fiction, with long and sometimes exhausting name-checks of brand names and detailed trivia (in that sense, much like his contemporary Ian Fleming with his Bond novels), along with a barely disguised contempt for the American political establishment in general and Richard Nixon (then the sitting vice president) in particular. A 1971 Time magazine profile memorably called the author “a riot in a satire factory.” There’s also the fact that Condon seems to have borrowed, to put it no stronger than that, certain passages of another writer’s work. A scholarly article published in 2003, seven years after Condon’s death, concluded that several paragraphs in The Manchurian Candidate appeared to be similar to portions of Robert Graves’ 1934 novel, I, Claudius. But then perhaps that’s only appropriate for a story that, after all, deals primarily with the concept of tapping into another human being’s mind.

I confess I’m always a bit skeptical when told that a certain book or film, or pretty much any other public offering, enjoyed an added popularity on its release because it “caught its time” quite as vividly as it did. Somehow I find myself wondering whether this might be more of a retrospective judgment on a given critic’s part, rather than a truly integral explanation of the product’s success in its initial offering. In this context, it seems unlikely that many Americans would have driven themselves to their nearest downtown bookstore (at a time when such things still existed) to buy a copy of The Manchurian Candidate because of its supposed allegorical insights into the culture. But it might nonetheless be fair to say that Condon’s themes struck a nerve. In 1959, we may remember, the U.S. and its allies were in the midst of a decades-long struggle for supremacy with the Soviet Union and its satellite states that George Orwell had presciently dubbed the Cold War. The public discourse at the time of the book’s publication was all about the recent Marxist-inspired revolution in Cuba, and more broadly Nikita Khrushchev’s issuing of an ultimatum on the question of occupied Berlin, the former Reich capital partitioned since 1945 between the victorious Allied powers. The divided city had become “a sort of malignant tumor,” Khrushchev announced at a rare Kremlin press conference in December 1958. Therefore, the USSR had “decided to do some surgery,” he noted ominously. As President Eisenhower, and much of the American public, recognized immediately that this marked the moment that concluded the policy of “grudging co-existence” at the front line of the Cold War, and the beginning of one that would lead to what Khrushchev coyly called “Operation Rose” and the erection of the communists’ “anti-fascist protection device”—or Berlin Wall, as others preferred to term it—some two and a half years later.

The Manchurian Candidate caught at least some of the essential spirit of its time, therefore, and in particular the widespread perception that domestic or foreign communists were hellbent on infiltrating or subverting American society and the instruments of the federal government. And if anxiety about communist brainwashing seems a prime example of Cold War paranoia, that fear was not entirely without basis. The North Koreans had regularly persuaded captured American troops to give radio speeches denouncing the U.S., and an Anglo-Dutch intelligence officer named George Blake went further than this when, turned by his Korean captors, he went on to serve as a double agent at the highest levels of the British security services until his eventual arrest and imprisonment in 1961.

Writing in December 1963, Condon himself noted that his book had sought to address the rather loftier theme of the “brainwashing” of American society to violence per se—and that this manifested itself in everything from “the sale of cigarettes after they have been conclusively demonstrated to be suicide weapons” to the “systemic racism” that “allows us to bomb little girls in a Sunday school,” while, looming above it all—with perhaps just an anticipatory touch of the eco-fundamentalist ravings of Ted Kaczynski—“We are power-hosed by the most gigantically complex overcommunications system ever developed.”

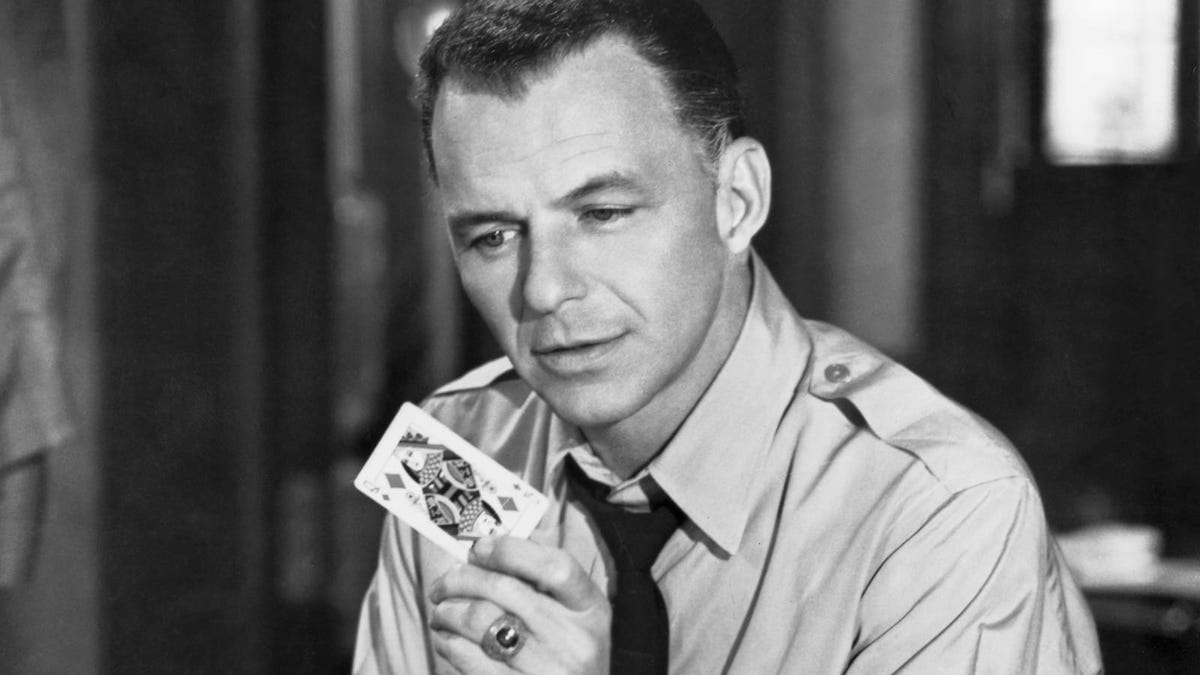

Again, one’s reluctant to give the first, and infinitely superior, movie treatment of Condon’s book, released 60 years ago this October, with Laurence Harvey and Frank Sinatra in the lead, undue prominence as a metaphor for its times. But the John Frankenheimer–directed film did at least have the morbid good fortune to appear in the very week the world exhaled again following the successful resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Cold War anxieties could hardly get any greater than this, although Frankenheimer himself always said he was proudest that the film hammered not Marxism but McCarthyism; there’s a scene, not included in the book, where the hard-drinking Senator Iselin can’t decide how many commies are in the State Department and settles on 57 after studying a ketchup bottle.

Just over a year later, The Manchurian Candidate seemed to take on a ghastly new significance following the Kennedy assassination. Apparently sane adults have speculated—and in many cases continue to speculate—that Lee Harvey Oswald was a brainwashed sleeper either of the CIA or some other domestic agency, hypnotized and programmed to act when his controllers pulled the psychological trigger. Following the events in Dallas in November 1963, Frank Sinatra purchased the rights to the film and kept it out of circulation for the next quarter of a century, stricken by remorse, apparently, at Kennedy’s death. Again, though, we should tread warily; the more one studies The Manchurian Candidate, the more it seems to defy the consensus interpretation. Frankenheimer himself later commented that the film had been pulled not so much for sentimental as more narrowly commercial reasons: Sinatra had a dispute with United Artists about the profits, and bought it out of pique, deciding it should earn no money for the studio or anyone else. Writing a month after the events in Dallas, Condon took what could be called the societal view of the matter. “Like all Americans,” he noted, “I contributed to form the attitudes of the [Kennedy] assassin. I suggested in my book that all of us in the United States have been numbed to violence, and indicated that the reader might consider that the tempo of this all-American brainwashing was being speeded up.”

Which somehow brings us to Jonathan Demme’s 2004 remake, starring Liv Schreiber and Denzel Washington in respectively the Harvey and Sinatra roles, and with Meryl Streep rather gamely on board as Schreiber’s notably dishonorable mother. Instead of the communists taking control, something called “big corporate influence” serves as the evil faction, and more particularly one fugitive biogeneticist from South Africa whose brainwashing techniques have been updated as surgical implants. That could have been a clever plot device—evoking classic Cold War paranoia by simultaneously modernizing it while preserving the essential xenophobia in comforting 1950s aspic. Unfortunately, Demme and his writer lose the plot and deliver something that’s not so much Manchurian as Manichean in its portrayal of Washington’s noble black character confronted by uniformly evil white bigots responsible for a whole host of social and political ills. Early in the film, one of the latter yells out in a thuddingly contrived reference to the protracted 2000 presidential election: “Falling chads caused delegates to hide under tables and run for the exits!” The scene has no wit or relevance to the plot—all it’s saying is that this new version of the film is crass and cynical in a failed attempt to be edgy.

The Manchurian Candidate redux managed to catch the zeitgeist sufficiently to be a modest success at the box office, but the takeaway question of the film is less Who are the real manipulators behind the scenes of American life? and more Why does Hollywood persist in making sequels to classic films? They’re inevitably inferior to the original. Why not revisit a bomb like Heaven’s Gate or Ishtar that you could only make better?

So if you want the more affecting adaptation of the Condon original, look no further than the film’s treatment by Frankenheimer, Sinatra, and company. Some of the set piece scenes might seem a little mannered, or theatrical, for modern tastes, but taken as a whole the film is a bona fide neglected masterpiece. Frankenheimer may lack Steven Spielberg’s facility to emotionally seduce an audience, but when it comes to the nuts and bolts of constructing a good drama, he’s easily his equal. I saw the film when it first came back into circulation in 1988, and it’s stayed in my mind because of the razor-sharp script and the compelling performances by Sinatra and Harvey, two actors, whatever else you can say about them, who knew what it took to project an air of latent menace, which should most definitely resonate with audiences in 2022.