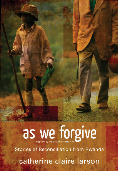

Catherine Claire Larson’s book As We Forgive: Stories of Reconciliation from Rwanda is an exploration of forgiveness and reconciliation in the years following the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Fifteen years ago this month, a plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down on a return trip from Tanzania, sparking widespread ethnic violence across the country. By the time the civil war was declared over on July 18, 1994, between 800,000 and 1 million Rwandans had been killed.

Catherine Claire Larson’s book As We Forgive: Stories of Reconciliation from Rwanda is an exploration of forgiveness and reconciliation in the years following the Rwandan genocide in 1994. Fifteen years ago this month, a plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi was shot down on a return trip from Tanzania, sparking widespread ethnic violence across the country. By the time the civil war was declared over on July 18, 1994, between 800,000 and 1 million Rwandans had been killed.

As We Forgive tells the tale of the war through the lives of seven survivors of the genocide. “Rwanda’s wounds,” writes Larson, “are agonizingly deep. Today, they are being opened afresh as tens of thousands of killers are released from prison to return to the hills where they hunted down and killed former neighbors, friends, and classmates.” Larson’s book is a study in the personal experiences of both the perpetrators and the victims who are seeking some way to live together after such a troubled past.

Through these individual stories Larson places the reader in the recent history of Rwandan society. She writes, “One of the most haunting things about living in Rwanda after the genocide is that killers still walk among survivors.” After the commission of such unspeakable evil, how can a society survive and prosper?

The need for forgiveness is deeply personal. Many of the killers have come to regret their actions, whether soon after the deeds were done or only after years of imprisonment and reflection. But in order for reconciliation to be achieved, both the offender and the victim must seek it. A traditional system of retributive justice, in which the evil committed is simply countered by punishment, lacks many of the tools necessary to bring both parties together.

In this sense As We Forgive is a book about the practice of a different form of justice. “Restorative justice,” writes Larson, “is a process in which victim, offender, and community are involved in dialogue, mutual agreement, empathy, and the taking of responsibility. In contrast to retributive justice, restorative justice focuses on balancing harm done by the offender with making things right to the victim, and on restoring human flourishing.”

But the important thing to note is that restorative justice is not simply about changing the institutional application of criminal justice. Many of the most critical aspects of processes of restorative justice are not achieved by courts, prisons, or police. Indeed, as Larson writes, “there are ways to infuse restorative elements into already established systems or to offer such programs on a voluntary community-wide level.” Larson explores the establishment of these systems and their influence in the lives of Rwanda’s victims, especially from a perspective that emphasizes the Christian doctrine of forgiveness.

Many of the most effective organizations working toward reconciliation in Rwanda do so out of specifically Christian convictions about the nature of sin, repentance, and forgiveness. The title of the book is taken from the petition in the Lord’s Prayer: “Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us” (Matthew 6:12).

One particular case in which this aspect of the book comes through is in the story of Claude. He was a thirteen year-old boy in 1994, when a grenade woke him from sleep and tore his world apart. Years after the end of the genocide, Claude held on hatred and lust for vengeance against those who had mutilated, hunted, and killed his family. Even while he was in school, Claude joined a group called the Survivors Club, which was intended to bring students together to share stories of their survival. But for Claude, “These tales only fanned the embers of something that had begun to burn deep within him and haunt his waking and his sleeping: revenge.”

It wasn’t until Claude became part of a different group, called Solace, that his perspective began to be transformed. “Like the Survivors Club at his school, this was a gathering of Tutsi who had managed to survive the genocide,” writes Larson. “The people who gathered were mainly divided into two groups: widows and orphans. But unlike the Survivors Club, this group sought consolation not simply from each other, but from God. Claude found that this wasn’t like being a member of an organization or society. Solace was like family to him.”

Interspersed between the seven stories of reconciliation in Rwanda are short reflective chapters that apply the moral and spiritual lessons to a North American context. Each one of us knows what it is like both to be wronged and to commit wrong against another. And therefore each one of us knows what it is like to need to forgive or to need forgiveness. While many of the wrongs we experience pale in comparison to the grisly crimes committed in those 100 days of horror fifteen years ago, these exceptional evils prove the necessity of overcoming even seemingly more banal and daily sins.

As We Forgive is a must-read for anyone interested in the recent history of Rwanda, the practice of restorative justice, or the Christian understanding of forgiveness and reconciliation.