Samuel Gregg, director of research at the Acton Institute, recently published a review of Maurice Cowling’s 1963 book Mill and Liberalism, in which Cowling warns of the tendency towards “moral totalitarianism” in John Stuart Mill’s “religion of liberalism.” Gregg acknowledges fifty-four years after Cowling’s warning, “significant pressures are now brought to bear on those whose views don’t fit the contemporary liberal consensus.” The book’s analysis “provides insights not only into liberal intolerance in our time but also into how to address it.”

Samuel Gregg, director of research at the Acton Institute, recently published a review of Maurice Cowling’s 1963 book Mill and Liberalism, in which Cowling warns of the tendency towards “moral totalitarianism” in John Stuart Mill’s “religion of liberalism.” Gregg acknowledges fifty-four years after Cowling’s warning, “significant pressures are now brought to bear on those whose views don’t fit the contemporary liberal consensus.” The book’s analysis “provides insights not only into liberal intolerance in our time but also into how to address it.”

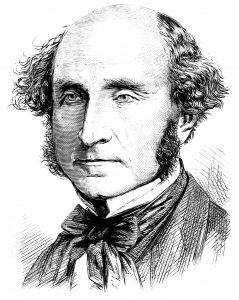

Mill was not the “secular saint of tolerance” many suggest he was. Instead, Gregg claims: “Mill’s liberalism itself constituted an evangelistic religious enterprise.” Mill’s gospel both embodied “universalistic aspirations” and sought “not to free men, but to convert them.” Gregg goes on:

[Mill] asserts (for he makes no effort to prove) that Christianity’s credentials no longer convince “a large proportion of the strongest and most cultivated minds, and the tendency to disbelieve them appears to grow with the growth of scientific knowledge and critical discrimination.”

In other words, thanks to modern science, most smart people no longer believe Christianity’s claims. The insinuation is that only less intelligent or unenlightened beings could cling to an obsolescent belief system… Mill’s path to liberalism’s Promised Land thus involves freeing everyone else from ideas and authorities that the clever find unconvincing.

Having rescued people from their illusions, Mill wanted societies to put their faith in the imperative of realizing the greatest happiness for the greatest number. In Utilitarianism (1861), Mill sought to devise an ethical system that would lead societies to promote happiness through following rules based on a calculus of pleasure and pain.

Gregg claims that “Mill’s religion of liberalism prefigures the sentimental humanitarianism that is central to today’s liberalism” as both invoke “values” that “turn out to lack grounding in any substantial account of the goods knowable through reason.”

Another insight into liberalism found in Cowling’s work is the priest-like duty of Mill’s “intellectual elite” who provide “a systematic indoctrination” of utilitarian principles. Gregg quotes Mill’s Inaugural Address to Saint Andrews University in 1867 in which Mill encourages educators, the “clerisy” of the religion of liberalism, to “direct [students] towards the establishment and preservation of the rules of conduct most advantageous to mankind.” According to Mill, the progress of these advantageous rules of conduct depended on the end of “dogmatic religion, dogmatic morality” and “dogmatic philosophy.”

In the 1800s, disdain for religion needed to be tempered, but in today’s cultural climate Gregg claims that “liberalism’s priests and priestesses no longer feign respect for the powerful arguments in favor of the reasonablitity of Christian faith defended… They increasingly won’t even tolerate Christians living according to the principles of Christian morality.”

If ‘liberalism in all thing except liberalism itself’ is the way of modern society, how do we address liberal intolerance? Gregg answers that we – like the “lovers of truth” that came before us, individuals like Paul, Augustine and Aquinas – must “contest the religion of liberalism on the terrain of what constitutes the reasonable faith and to dispute the clerisy’s claim to a monopoly of reason.”

To read Gregg’s complete article published by The Witherspoon Institute click here.