Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty made a mistake of historic proportions at the 2017 Academy Awards, when they mistakenly awarded the Oscar for “Best Picture” to La La Land. They should have awarded it to The Founder, the new biopic about McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc which, alas, did not garner any Oscar nominations.

I saw The Founder on February 8. By happenstance, that is the birthday of Joseph A. Schumpeter, the Viennese economist whose key contribution to his discipline was his analysis of entrepreneurship. The fortuitous pairing proved a match made in Heaven.

I saw The Founder on February 8. By happenstance, that is the birthday of Joseph A. Schumpeter, the Viennese economist whose key contribution to his discipline was his analysis of entrepreneurship. The fortuitous pairing proved a match made in Heaven.

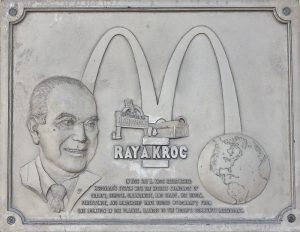

The film depicts how McDonald’s grew from a regional chain to a global phenomenon that revolutionized the food industry through the insight of one man: Ray Kroc (Michael Keaton). While selling milkshake machines at their San Bernardino restaurant, he encounters Dick and Mac McDonald (Nick Offerman and John Carroll Lynch) and sees in their efficient and innovative store model something far more than a potentially successful burger stand. In a bid to convince the brothers to let him franchise the store, Keaton tells them:

I drove through a lot of towns – a lot of small towns – and they all had two things in common. They had a courthouse, and they had a church. On top of the church, got a cross. And on top of the courthouse, they’d have a flag. Flags, crosses; crosses, flags. I’m driving around. And I just cannot stop thinking about this tremendous restaurant. Now, at the risk of sounding blasphemous, forgive me, those arches have a lot in common with those buildings.

A building with a cross on top – what is that? It’s a gathering place where decent, wholesome people come together, and they share values protected by that American flag. It could be said that that beautiful building flanked by those arches signifies, more or less, the same thing. It doesn’t just say, delicious hamburgers inside. They signify family. It signifies community. It’s a place where Americans come together to break bread. I am telling you, McDonald’s can be the new American church – feeding bodies and feeding souls, and it’s not just open on Sundays, boys. It’s open seven days a week.

Crosses, flags, arches.

Fueled by that vision, Kroc – who is portrayed as a lonely mediocrity and burgeoning alcoholic – single-handedly builds a national network of franchisees, eschewing wealthy absentee owners in favor of giving middle class couples a shot at the American Dream. Along the way, he and the brothers increasingly clash over goals, as well as means. Finally in 1961 the 59-year-old muscles the brothers out of their eponymous business (and the legal rights to their surname), reneges on a (not legally binding) “handshake deal” to continue profit-sharing with them, and divorces his first wife, Ethel.

Such a film could easily devolve into caricature, but the script and Keaton’s pitch-perfect performance (one of several) maintains dramatic balance. (Laura Dern, one of the finest actresses of her generation, also deserves credit for getting the most out of the script, which gives her little more to do than look forlorn.) It was Kroc who did all the legwork to recruit franchisees, who standardized production, assured quality control, and nearly went bankrupt promoting their business while they cashed the checks and seemed intent on placing every conceivable barrier in his way.

Thanks to the pacing of director John Lee Hancock, when Kroc’s ruthless ways appear, it seems less like a transformation – in the sense of Michael Corleone or Anakin Skywalker – from hero to villain than a deeper revelation of Kroc’s multifaceted personality.

The script omits key aspects of Kroc’s relationship with the brothers – like the fact that, when he went to open his own restaurant in 1955, he had to pay a rival company $25,000 because the McDonald brothers had already licensed the area out from under him. Kroc revealed that he “could not afford” the price – nearly a quarter of a million dollars today – because he “was already in debt for all I was worth” from promoting their brand. Kroc’s inexcusable reactions are never presented as the inevitable byproduct of the free market, making the film less than a full-throated brief against capitalism.

The Founder serves as much as an eloquent petition for subsidiarity. Bureaucracy, embodied by the McDonald brothers, is portrayed as remote, unresponsive, uninformed, and indifferent to others. Kroc felt responsible for the young families he had recruited, leading him to come up with an innovative solution to keep them from financial ruin. Had Dick and Mac been willing to delegate to Kroc – or even learn from the objective failure of their methods and the success of his – the story may well have ended differently.

So, what would the economist most associated with entrepreneurship say about all of this?

Schumpeter, and two popes, on entrepreneurship

Joseph A. Schumpeter died in 1950, three years before the McDonald brothers began franchising their assembly line “Speedee Service System.” Despite his intellectual flexibility, he is remembered for his celebration of entrepreneurial innovation.

The entrepreneur, to Schumpeter, is not just anyone who starts a new business. A person qualifies as an entrepreneur by introducing “an untried technological possibility for producing a new commodity or producing an old one in a new way,” or “by reorganizing an industry.” That ingenuity allows the economy to break out of its circular process of replicating existing businesses. The “creative destruction” of outmoded businesses – Mom-and-Pop stores like the brothers envisioned – serves that end, he wrote.

He would have seen Kroc, rather than the McDonald brothers, as the innovator. “The pure new idea is not adequate by itself to lead to implementation,” Schumpeter wrote. It is not part of the entrepreneur’s function “to ‘find’ or to ‘create’ new possibilities. They are always present … But nobody was in a position to do it.” His key criterion is “doing the thing.” The entrepreneur, like Kroc, succeeds “more by will than by intellect … more by ‘authority,’ ‘personal weight,’ and so forth than by original ideas.”

Schumpeter had more in common with Kroc than the McDonald brothers on a personal level. He, too, failed miserably when his would-be magnum opus – a ponderous, two-volume rival to John Maynard Keynes’ General Theory – was a bust. Schumpeter stood accused of an extraordinary willingness to modify his views in order to advance his career, and he confided to his diary: “I … have no garment that I could not remove. Relativism runs in my blood. That is one of the reasons I can’t win.” (His amoral penchant for disrobing extended to his personal life, as well.)

However, one need not be an academic libertine to see the entrepreneurial vocation as one of the greatest forces in service of mankind. In a series of radio addresses in the 1950s, Pope Pius XII said that the entrepreneur “arouses latent and sometimes unexpected energies, and stimulates the spirit of enterprise and invention,” which makes him of “great benefit to the community.” The world suffered, he said, from those too “short-sightedly timid” to follow “the indispensable functions of the private entrepreneur.” (For more, see “Private Initiative, Entrepreneurship, and Business in the Teaching of Pius XII” by Anthony G. Percy in the Spring 2004 issue of Markets and Morality.) Pope John Paul II would praise “initiative and entrepreneurial ability” in Centesimus Annus.

Schumpeter, too, understood service, and elevating the least well-off, as the heart of innovation:

The capitalist engine is first and last an engine of mass production which unavoidably also means production for the masses. … The capitalist achievement does not typically consist in providing more silk stockings for queens but in bringing them within reach of factory girls in return for steadily decreasing amounts of effort.

That may be McDonald’s least celebrated accomplishment. Stephen Dubner of Freakanomics asked his readers to debate whether the McDouble was “the cheapest, most nutritious, and bountiful food that has ever existed in human history.” “Where else but McDonald’s can poor people obtain so many calories per dollar?” replied New York Post columnist Kyle Smith. Their queries provoked a newfound appreciation of the franchise’s social contribution, made without any philanthropic intent except to serve their consumers well.

“The biggest unreported story in the past three quarters of a century,” said Blake Hurst, president of the Missouri Farm Bureau during that debate, is “this increase in availability of food for the common person.” Yet today, McDonald’s is the subject of boundless disapprobation, as are genetically modified foods (GMOs) – another safe and innovative source of nutrition.

Ray Kroc was not the inventor of the McDonald’s process, and his business ethics were sometimes indefensible. But his foresight, and his alone, brought a new service – and low-cost protein – to “billions and billions.”

Supporters and critics of the free market alike should agree that The Founder is worth seeing, and Kroc worth appreciating in all his complexity.

(Photo credit: Phillip Pessar. Cropped. CC BY 2.0.)