Earlier today Freedom House released the 2017 edition of their flagship report, “Freedom in the World.” It was not positive. Titled “Populists and Autocrats: The Dual Threat to Global Democracy,” it shows much erosion in various freedoms throughout the world.

According to their website, Freedom House has published this important report since 1973 in order to track trends and view democracy and civil liberty from a large, global point. The organization evaluates countries and decides a ranking by analyzing “electoral process, political pluralism and participation, the functioning of the government, freedom of expression and of belief, associational and organizational rights, the rule of law, and personal autonomy and individual rights.”

The key findings in the 2017 report:

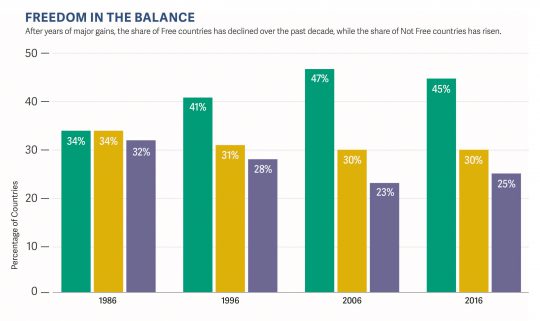

- It is the 11th consecutive year of greater global declines in freedom than gains in freedom

- Many “free” countries saw a loss in political rights and/or civil liberties, including the United States and South Korea

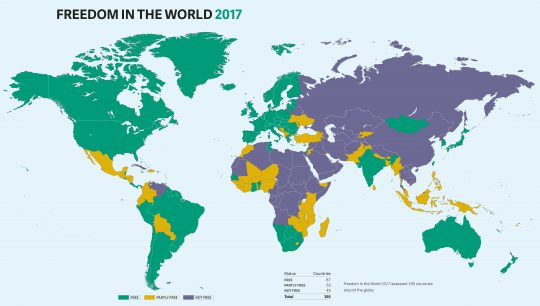

- 195 countries were assessed and a fourth of them were rated “Not Free.”

- The breakdown:

- Free: 45 percent

- Partly free: 30 percent

- Not free: 25 percent

- The worst rated countries were in the Middle East and North Africa

In an essay summarizing the report, Arch Puddington and Tyler Roylance explain much of the data. “The troubling impression created by the year’s headline events is supported by the latest findings,” they explain. “A total of 67 countries suffered net declines in political rights and civil liberties in 2016, compared with 36 that registered gains.” They included an especially dark note:

While in past years the declines in freedom were generally concentrated among autocracies and dictatorships that simply went from bad to worse, in 2016 it was established democracies—countries rated Free in the report’s ranking system—that dominated the list of countries suffering setbacks. In fact, Free countries accounted for a larger share of the countries with declines than at any time in the past decade, and nearly one-quarter of the countries registering declines in 2016 were in Europe.

The United States was given special attention in the report. Freedom House included a section to address the 2016 presidential election in the United States. “The success of Donald Trump,” the section began, “demonstrated the continued openness and dynamism of the American System.” But more importantly, his election “demonstrated that the United States is not immune to the kind of populist appeals that have resonated across the Atlantic in recent years.” It named the United States as a “country to watch” because Trump’s unusual campaign “left open questions about [his] administration’s approach to civil liberties and the role of the United States in the world.”

The United States received 89/100 aggregate score (100 being the most free) and a 1/7 freedom rating (1 being the most free). The overview of the United States notes:

The United States remains a major destination point for immigrants and has largely been successful in integrating newcomers from all backgrounds. However, in recent years the country’s democratic institutions have suffered some erosion, as reflected in legislative gridlock, dysfunction in the criminal justice system, and growing disparities in wealth and economic opportunity.

Ultimately, U.S. democracy suffered some loss last year. The aggregate score in the 2016 report was 90.

Freedom House’s “worst of the worst” included 49 countries labeled “not free.” The worst three offenders were Syria, Eritrea, and North Korea.

On a somewhat positive note, under “trend arrows,” Colombia received an upward trend “due to the peace process between the government and left-wing FARC [Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia or Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia] guerrillas, leading to a reduction in violence.” Unfortunately Colombia was the only country with an upward trend arrow. Colombia’s aggregate score is 64 and the nation is only considered “partly free.”

As we move into 2017 it is important to understand:

In the wake of last year’s developments, it is no longer possible to speak with confidence about the long-term durability of the EU; the incorporation of democracy and human rights priorities into American foreign policy; the resilience of democratic institutions in Central Europe, Brazil, or South Africa; or even the expectation that actions like the assault on Myanmar’s Rohingya minority or indiscriminate bombing in Yemen will draw international criticism from democratic governments and UN human rights bodies. No such assumption, it seems, is entirely safe.

There is also a PDF available in Spanish.

Last year’s report also noted a general decline in global freedom, including in the United States.