In an Acton Commentary two years ago, I wrote about the significance of toil:

In an Acton Commentary two years ago, I wrote about the significance of toil:

In the midst of the now-common Christian affirmation of all forms of work as God-given vocations, the image of Sisyphus, vainly pushing his boulder up a hill in Hades, only to watch it roll back down again, might serve to remind us of the reality of toil, the other side of the coin. While human labor does have a divine calling, we do not labor apart from “thorns and thistles” and “in the sweat of [our] face” (Genesis 3:18-19).

As for the good side of work in general, I can’t think of a better illustration than this clip from For the Life of the World:

This shows the amazing reality of how everything we interact with is the fruit of the labor of others. It connects us to them and ought to inspire a deep gratitude for that fellowship.

But then there’s Sisyphus.

Sisyphus can be seen in the picture at the top right of this post, looking somewhat heroic. No doubt, this is closer to how the French existentialist Albert Camus imagined him when he claimed, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

For Camus, Sisyphus represented all our endeavors in a world that is ultimately meaningless. He advocated the ideal of an absurd way of life, believing that there was no inherent meaning to life but that which one creates. Thus, we must imagine Sisyphus heroically happy, because he knows the futility of his task but chooses to do it anyway.

For a more nihilist type, however, Sisyphus might be better portrayed as he is in this medieval manuscript:

Sisyphus doesn’t look too heroic here, not to mention happy. Indeed, many feel the toil of work to be crushing, and I do not think we should gloss over the real suffering it can bring.

That said, I still believe, as I argued two years ago, that the curse of toil can itself be grace. I wrote,

Our life is plagued by imperfection and the tragedy of our mortality, but nevertheless God says to Adam, “you shall eat,” that is, “you shall have the means to sustain your life.” Work ought not to be so toilsome — toil, in that sense, is a bad thing — but given that our lives are characterized by sin, sometimes we actually need toil. Sometimes the curse is also grace.

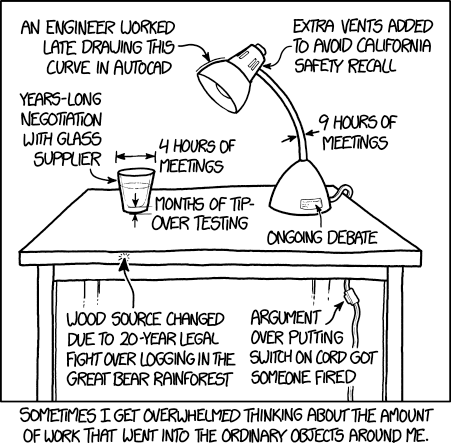

Perhaps part of the problem is that we fail to see not only the work but the toil beneath the blessings of life as well. The webcomic XKCD recently featured a drawing that could serve as a play on Leonard Read’s I, Pencil, specifically emphasizing the persistence of toil in modern economies:

Toil can be formative. Contra Camus, it can, in fact, be meaningful in itself, and according to Genesis it was designed to be that way. But that does not mean we should be indifferent to it.

The fruit of toil should serve to inspire not only gratitude but also a desire to ease the toilsome burdens of those who have so generously provided for our needs.