Lester DeKoster’s short book, Work: The Meaning of Your Life, sets forth a profound thesis and solid theological framework for how we think about work.

Lester DeKoster’s short book, Work: The Meaning of Your Life, sets forth a profound thesis and solid theological framework for how we think about work.

Although the faith and work movement has delivered a host of books and resources on the topic, DeKoster’s book stands out for its bite and balance. It is remarkably concise, and yet sets forth a holistic vision that considers the multiple implications of the Christian life.

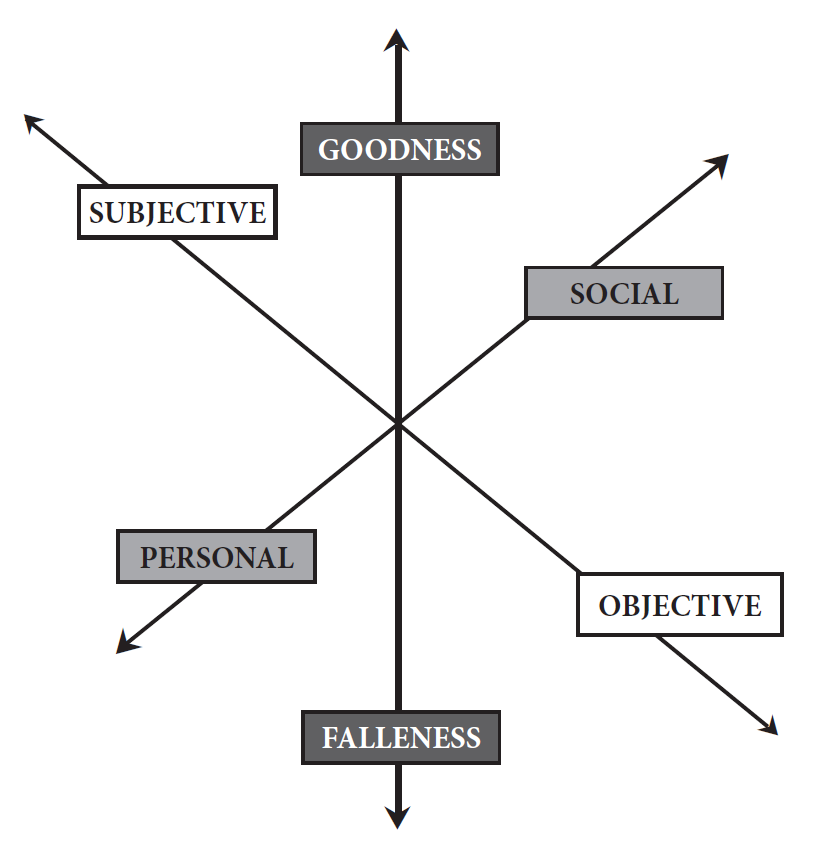

The book was recently re-issued, along with the new afterword by Greg Forster. In it, Forster outlines DeKoster’s underlying framework, which “invites us to view work as a complex, three-dimensional reality.” Each of these dimensions is summarized as follows (quoted directly from Forster).

1. Objective-Subjective

One dimension of our work is defined by the distinction between objective and subjective. No matter how pious your feelings about it are, it still matters to God whether your work is actually having a beneficial effect on other people. At the same time, human dignity and the shaping of the self for God can only be lived out if we do our work with the right sense of identity and motives. We see this dimension most clearly in DeKoster’s twofold understanding of God’s presence in our work—that we love God in our work by serving our neighbor (objectively) and shaping ourselves (subjectively).

2. Goodness-Fallenness

The second dimension is defined by goodness and fallenness. Theologically, the goodness of God in our work must be primary, lest we compromise our conception of his transcendence or deny the gospel truth that Christ has overcome the world. But for many people, the daily experience of work is overwhelmed by the brokenness of the fall and the curse. The Christian virtue of hope addresses itself to the experience of suffering and evil with a message of victory and light.

3. Personal-Social

The third dimension is defined by the personal and social. Each individual is an executive steward, with agency and responsibility. We must not turn inward and use our work or our wages as opportunities to serve ourselves, but must use them instead to serve the needs of our households and communities. The community, in turn, must honor each individual as an executive steward, sustaining systems of work and exchange that are just and provide the necessary context of freedom and responsibility.

As Forster notes, and as DeKoster thoroughly acknowledges, this is not to say that all human experience can be simplified and classified according to certain categories. Rather, these are simply aspects of work as we encounter it and as we ought to encounter it as Christians.

As Forster notes, and as DeKoster thoroughly acknowledges, this is not to say that all human experience can be simplified and classified according to certain categories. Rather, these are simply aspects of work as we encounter it and as we ought to encounter it as Christians.

Far too often, we’re tempted to lean or meditate too heavily on one dimension or particular extreme to the detriment of the other. By recognizing the bigger picture of God’s design for work, DeKoster’s vision points to “new directions for growth,” Forster writes, “shining the light of Christ into a dark and dying world.”