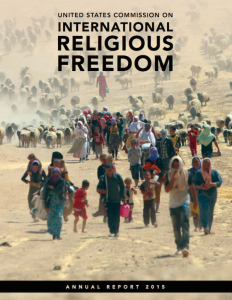

The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has issued its 2015 annual report on religious liberty around the world. In their report, the USCIRF documents religious freedom abuses and violations in 33 countries and makes county-specific policy recommendations for U.S. policy. One country worthy of particular attentions is Afghanistan.

For the past nine years USCIRF has designated Afghanistan as a country of particular concern, a country where the violations engaged in or tolerated by the government are serious and are characterized by at least one of the elements of the “systematic, ongoing, and egregious” standard. As the report notes,

For the past nine years USCIRF has designated Afghanistan as a country of particular concern, a country where the violations engaged in or tolerated by the government are serious and are characterized by at least one of the elements of the “systematic, ongoing, and egregious” standard. As the report notes,

Afghanistan’s legal system remains deeply flawed, as the constitution explicitly fails to protect the individual right to freedom of religion or belief, and it and other laws have been applied in ways that violate international human rights standards.

Notice that the country has been on the list since two years after the adoption of their new constitution—a constitution that the U.S. helped to create.

In 2004, after U.S. military and allied forces overthrew the Taliban, American diplomats helped draft a new Afghani constitution. Many people around the world were hoping the result would be similar to the constitution of Turkey—or at least be distinguishable from the constitution of Iran. Instead, what was created—with the help of the U.S. government—was an Islamic Republic, a state in which “no law can be contrary to the sacred religion of Islam.”

While the White House issued a statement calling it an “important milestone in Afghanistan’s political development,” the USCIRF had the courage to admit what we were creating: Taliban-lite.

As USCIRF claimed at the time, “the new Afghan draft constitution fails to protect the fundamental human rights of individual Afghans, including freedom of thought, conscience and religion, in accordance with international standards.” The commission was right. Today there is not a single, public Christian church left in Afghanistan, according to the U.S. State Department.

A year later, in 2005, the Iraqi government—again with the help of the U.S. government—drafted a constitution that also made that country an Islamic republic and included the same language: “no law can be contrary to the sacred religion of Islam.” The Iraqi constitution did, however, include a guarantee that, “The state guarantees freedom of worship and the protection of the places of worship.”

That guarantee existed only on paper. Since the adoption of their constitution, the Iraqi government has failed to protect non-Islamic citizens from religious persecution. As the latest USCIRF report notes, 2 million people in Iraq were internally displaced in 2014 as a result of ISIL’s offensive.

Because of this persecution, the USCIRF has recommended to the State Department that Iraq (along with seven other countries) be designated as “countries of particular concern” for their “systematic, ongoing and egregious” violations of religious freedom. Despite such recommendations, the USCIRF is more often than not, simply ignored. Powerful lobbyists from countries such as China, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and India are no doubt putting pressure on Senators to dismiss the commission or do away with USCIRF completely. They are the only ones to benefit from the commission’s dissolution.

As Nina Shea, a former USCIEF commissioner has said, “USCIRF is one reliable voice within the government that does not find the issue of religious freedom too sensitive to bring up with foreign potentates.”

USCIRF was created in 1998 to “monitor religious freedom in other countries and advise the president, the secretary of state, and Congress on how best to promote it.” Since then the commission has frustrated and annoyed foreign persecutors and their American apologists. At the time of the commission’s founding Congress believed that the foreign policy establishment was not giving due attention to issues of religious liberty.

Eliot Abrams, a former chairman of the commission, said in a 2001 interview that, “The State Department, the media, and the lobbies were very interested in things like freedom of the press, independent judiciaries, fair trials, and free elections, but much less interested than they should be in freedom of religion. Many members of Congress felt that this was because too many people in the foreign policy establishment were pretty secular themselves.”

In a world filled with religious believers, having a foreign policy establishment comprised of committed secularists makes as much sense as hiring linguists at the State Department who refuse to speak any language but English. Russell Kirk wisely acknowledged that, “At heart, political problems are moral and religious problems.” Failing to recognize this fact leads us to misdiagnose and treat the political problems we face.

Rather than trying to secretly dismantle the USCIRF (as happened a few years ago) or ignore their recommendations (as is mostly happening now), Congress and the President should give the commission a more active role in policymaking. The joint freedoms of religion and conscience constitute the “first freedom” and are deserving of protection both in our own country and abroad. Indeed, the moral center and chief objective of American diplomacy should be the promotion of religious freedom. Nathan Hitchen explains why:

The logic is that religious freedom is a compound liberty, that is, there are other liberties bound within it. Allowing the freedom of religion entails allowing the freedom of speech, the freedom of assembly, and the liberty of conscience. If a regime accepts religious freedom, a multiplier effect naturally develops and pressures the regime toward further reforms. As such, religious liberty limits government (it is a “liberty” after all) by protecting society from the state. Social pluralism can develop because religious minorities are protected. And the prospect of pluralism in the Middle East is especially enticing as it potentially combats the spread of Islamic radicalization.

In the post-9/11, pre-Iraq War era, I subscribed to the project of democracy promotion precisely because I believed it would lead to an expansion of religious liberty in the Middle East—and hence lead to the outcomes that Hitchen argues would flow from religious openness and pluralism. I now recognize that democracy alone is insufficient for securing security or diplomatic progress, as we learned in 2006 when the Palestinian National Authority elected Hamas in democratic elections.

Of course, religious liberty promotion is no more a political science panacea than was democracy promotion. But as Hitchen notes, “Religious liberty would help society grow so complex that no totalizing ideology, no philosophical monism, could feasibly dominate the public square, because no single ideology would accurately reflect social reality.”

That’s a modest goal, no doubt, but one worthy of being embraced by Christians. A world where everyone can worship freely is a safer world for everyone.