With its authorization charter expiring at the end of September, the U.S. Export-Import Bank has come under increased scrutiny from rabble-rousers and the hum-drum alike. An otherwise obscure fixture in the grand scheme of federal-government corporatism, Ex-Im finances and insures (i.e. subsidizes) foreign purchases of U.S. goods for those who wouldn’t otherwise accept the risk.

So far, we’ve seen a variety of good arguments made against the bank. It privileges certain companies over others. It doesn’t meaningfully improve national exports, despite many claims to the contrary. It will surely yield losses for taxpayers. And so on.

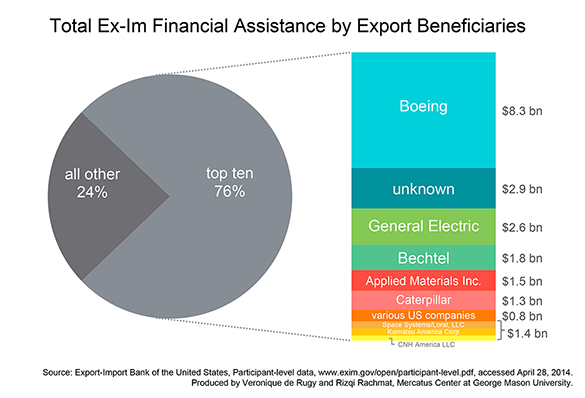

But there’s a bigger and broader reason to reject such schemes that has less to do with line-item analyses of exports vs. imports or how much Boeing will benefit vs. General Electric, and more to do with how they distort, inhibit, or prevent the efforts of those aren’t on the radar in the first place, but perhaps should or could be — the “unseen,” as Bastiat would call them.

Over at Economic Intelligence, Veronique de Rugy does us a service in highlighting this aspect, noting that Ex-Im and other corporatist schemes tend to cramp the economy at large by distorting signals and inhibiting innovation and possibility outside of the privileged few:

However, the real problem with Ex-Im pertains to the many groups who are affected by Ex-Im activities but have been ignored so far. These people don’t have connections in Washington, and they don’t have access to press offices and lobbyists. But they matter, too.

It is difficult, but extremely important, that we consider the unseen costs of political privilege, whether they take the form of market distortions, resource misallocation, job losses, destroyed potential or higher prices…

…These capital market distortions have ripple effects. Subsidized projects attract more private capital while investors overlook other worthy projects. The subsidized get richer while the unsubsidized get poorer or go out of business.

Unfortunately, we’ll never see the businesses that could have been. Perhaps they would have been better, more efficient or more responsible than politically connected firms. But how about the negative impact the bank has on jobs? Unsubsidized employers may not expand hiring, or may not increase wages, or may even have to fire employees because they face Ex-Im subsidized competition. (emphasis added)

To some, this will sound like typical “pro-market,” “pro-competition” boilerplate, but such alarms ought to redirect our minds and imaginations to the people themselves.

Remember, all of those distorted and inhibited ideas, innovations, and efforts are driven by complex processes of creativity, collaboration, and vocational discernment, born out by image-bearers who were created to steward things carefully, fairly, and generously. What does such a peculiar use of power and privilege do to disrupt such an order?

This applies to Ex-Im, but it’s the central question we should ask when confronting all such schemes — price-fixing, risk-insulating, king-making, or otherwise.

It’s become popular for Christians to talk about the bottom-up processes of prayer, discipleship, and stewardship in the workplace. Although we should be thankful that we live in a country where we are freer than most to live these activities out, we should remember that such endeavors also require a care and concern for proper stewardship from the top-down.

If something as obscure as Ex-Im is difficult to topple, we’ve got our work cut out for us.

For more on Ex-Im, Tim Carney offers good insight in the following interview:

[product sku=”1157″]