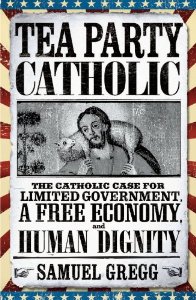

Sam Gregg, Director of Research for Acton, is featured in an interview with the National Catholic Register. The interview ranges from Gregg’s education and career at Acton to how Catholicism and the free markets dovetail.

Sam Gregg, Director of Research for Acton, is featured in an interview with the National Catholic Register. The interview ranges from Gregg’s education and career at Acton to how Catholicism and the free markets dovetail.

Trent Beattie questioned Gregg about St. Bernadine of Siena, who defended business and entrepreneurs. Gregg replied:

Most Catholics are unaware of the broad Catholic intellectual and institutional contributions to the development of market economies in general, especially during their early phases in the Middle Ages. Too often, we buy into the “Dark Ages” mythology about this period. So the fact that St. Bernardine of Siena — and many other Franciscans — were among the first to grasp the importance of the entrepreneur as a key catalyst for economic growth, or that they made clear and important distinctions between money-as-sterile and money-as-capital, get missed alongside all the other things that happened in the so-called “Dark Ages.”

I also think that many people have an imaginary understanding of St. Francis and the Franciscan orders that followed in his wake. They weren’t all poor mendicants. Lots of them were very intellectually serious men who lived, worked and often taught in urban centers, and thus experienced what some scholars have called the Commercial Revolution of the Middle Ages. They didn’t try to resist it. Rather, they sought to understand it so that they could guide the faithful in the “how” of living a Christian life in the midst of this new world.

To my mind, the misconceptions of Catholics are no different from those of most other people.

One of them is the notion that wealth is a fixed amount. This is called the “zero-sum game” fallacy. It implies that one person can only become wealthy by other people becoming poor. Entrepreneurship and the right institutions in place (especially the rule of law) are the factors that nullify that myth.

Another misconception is how the economic value of something is determined. It’s not through the labor that creates an object or service. Rather, it’s through the subjective value that is attached to the good or service by hundreds of thousands of people in a market place. The price of a book I write is not determined by how many hours I spent working on it, but by what people are willing to pay for it. And what they are willing to pay for it is determined by how much they want it compared to all the other books, services and goods they want.

Then there is the notion that free trade can only benefit the wealthy or wealthy countries. Again, if you look at the stories of how nations escape poverty, it’s not through subsidies, protectionism and closed markets. Rather, it’s through entering what St. John Paul the Great called the circles of exchange and embracing institutions such as rule of law.