I recently expressed my reservations about David Platt’s approach to “radical Christianity,” noting that, outside of embracing certain Biblical constraints (e.g. tithing), we should be wary of cramming God’s will into our own cookie-cutter molds for how wealth should be carved up and divvied out.

I recently expressed my reservations about David Platt’s approach to “radical Christianity,” noting that, outside of embracing certain Biblical constraints (e.g. tithing), we should be wary of cramming God’s will into our own cookie-cutter molds for how wealth should be carved up and divvied out.

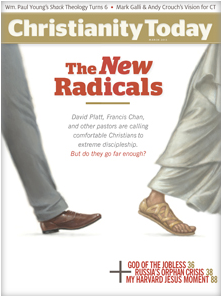

In this month’s cover story in Christianity Today, my good friend Matthew Lee Anderson of Mere Orthodoxy does a nice job of summarizing some additional issues surrounding the broader array of “radical Christianity” books and movements.

Sprouting from a diverse set of personalities ranging from Platt to Shane Claiborne to Kyle Idleman to Francis Chan to Steven Furtick, “the radical message has found an eager market,” Anderson explains, with sermons and books that “have both incited and tapped into a widespread dissatisfaction with many Americans’ comfortable, middle-class way of life and the Christianity that so easily fits within it.”

Anderson appreciates the energy and sincerity of those seeking to subvert “comfortable Christianity,” but offers a helpful critique of the overall urgency of things, beginning with an observation of the movement’s “reliance on intensifiers”—a reality that, for Anderson, demonstrates a distinct blind spot:

These teachers want us to see that following Christ genuinely, truly, really, radically, sacrificially, inconveniently, and uncomfortably will cost us…The reliance on intensifiers demonstrates the emptiness of American Christianity’s language. Previous generations were content singing “trust and obey, for there’s no other way.” Today we have to really trust and truly obey. The inflated rhetoric is a sign of how divorced our churches’ vocabulary is from the simple language of Scripture.

And the intensifiers don’t solve the problem. Replacing belief with commitment still places the burden of our formation on the sheer force of our will. As much as some of these radical pastors would say otherwise, their rhetoric still relies on listeners “making a decision.” There is almost no explicit consideration of how beliefs actually take root, or whether that process is as conscious as we presume.

This gap becomes further evident, Anderson argues, when one observes the narrow range and overly dramatic thrust of the narratives and testimonies held up by the movement:

The heroes of the radical movement are martyrs and missionaries whose stories truly inspire, along with families who make sacrifices to adopt children. Yet the radicals’ repeated portrait of faith underemphasizes the less spectacular, frequently boring, and overwhelmingly anonymous elements that make up much of the Christian life…

…there aren’t many narratives of men who rise at 4 A.M. six days a week to toil away in a factory to support their families. Or of single mothers who work 10 hours a day to care for their children. Judging by the tenor of their stories, being “radical” is mainly for those who already have the upper-middle-class status to sacrifice.

This connects with some of the big-picture economic issues I raised in my review of Platt’s first book. In a world wherein Christian masses sign onto Radical Plan X, Y, or Z—whether it means capping incomes at $50,000, donating anything “left-over” to philanthropy or missions, or quitting our jobs to participate in “new monasticism”—society would quickly begin to see the emergence of yet another variation of lopsided Christian mission, one that neglects the meaning of our daily work and further confines stewardship to immediate needs rather than unleashing it toward Spirit-led, transcendent ends.

Of course, this all goes well beyond economics. As Anderson concludes, we would do well to “test ourselves” with a “revived attention to form.” This, I would add, must also include a revived attention to the full scope of institutions we are called to transform:

Interior-oriented movements can generate a lot of energy initially. But the gospel is supposed to create a culture, and a culture takes root only within a society over time. It perpetuates itself to future generations without requiring a new revival in every season. The urgent rhetoric of preaching the gospel to the billion unreached and helping the poor right now leaves little space to create the institutions and practices (art, literature, theology, liturgy, festivals, etc.) that can transmit such an inheritance to the next generation, and to form belief in deeper and more permanent ways. Buildings cost money, and beautiful buildings even more. Universities don’t feed the poor or win souls, yet they promulgate knowledge in the church and around the world…

…For us in the pews, testing ourselves must include deliberating about our vocations and whether we are called to missions, or to a life of dedicated service to the poor, or to creating reminders with art and culture of the gospel’s transcendent, everlasting hope. Discovering a radical faith may mean revisiting the ways in which faith can take shape in the mundane, sans intensifiers. It almost certainly means embracing the providence of God in our witness to the world. The Good Samaritan wasn’t a good neighbor because he moved to a poor part of town or put a pile of trash in his living room. He came across the helpless victim “as he traveled.”

Read the full article here.

To join our efforts in furthering the doctrine of common grace and reviving Christian attention to broad cultural engagement, join the On Call in Culture community by liking us on Facebook or following us on Twitter.