As I noted yesterday, I’m in Montreal for the next couple of weeks, and today I had the chance to see some of the student protests firsthand. These protests have been going on now for over three months, and have to do with the raising of tuition for college in Quebec.

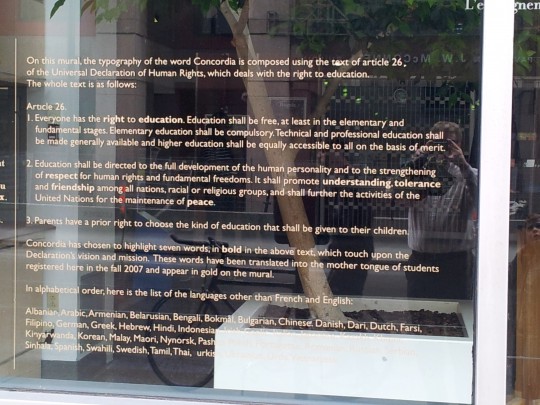

I’m teaching at Farel Reformed Theological Seminary, which is located in the heart of downtown Montreal, and is adjacent to Concordia University. As I walked around earlier this week, I noticed the following on one of Concordia’s buildings:

The text is article 26 of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which reads in part, “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages.”

I think that the kinds of protests we are seeing in Quebec might be the inevitable end of the logic of the welfare state. The logic goes something like this:

Education is a right, and should be free, or the next best thing to it. In order for it to be “free,” it must be administered, or at least underwritten, by the state, because we know that the only way to make something appear to be free is to requisition the necessary funds via taxation. This is, in fact, precisely the rationale for the existence of the modern welfare state, in which in the context of the Netherlands, for instance, it is understood to be “the task of the state to promote the general welfare and to secure the basic needs of people in society.”

Education is a right (per the UN Declaration), is constitutive of the general welfare, and a basic need. Thus it must be “fully guaranteed by the government” (to quote Noordegraaf from the Dutch context regarding social security, mutatis mutandis).

The upheavals we are seeing, then, are what happen when we can no longer sustain such guarantees. They are what happen when “free” becomes unaffordable and unsustainable.

This means that the flawed logic of the welfare state will have to be critically reexamined, no small task for a developed world that has steadily built infrastructure according to logic for much of the past seventy years.

For Quebec this does not bode well, as Cardus’ Peter Stockland puts it, “This is a province in the grip of reactionary progressives afflicted with severe intellectual and institutional sclerosis. Their malaise prevents any proposals for change from being given fair hearing, much less a chance of being put into play. Real change, not merely revolutionary play-acting, is anathema in this province.”