The publicists at the BBC weren’t thrilled, one imagines, when their Doctor Who leading man spoke candidly about why he loved the program so much. “People always ask me, ‘What is it about the show that appeals so broadly?’” Peter Capaldi said in 2018. “The answer that I would like to give—and which I am discouraged from giving because it is not useful in the promotion of a brand—is that it’s about death.”

He’s right (and as a fan since the age of five, he’d know). Underneath the whimsy of Doctor Who’s premise—an idiosyncratic alien travels time and space in an iconic blue police phone box—is a story of loss, exile, sehnsucht … of what it means to be mortal and immortal. Mind, it’s also about killer robots. One of its catchphrases is “reverse the polarity of the neutron flow,” and another the order a staid brigadier gives his men when confronted with a demonic being: “Chap with the wings, there. Five rounds, rapid!” The eponymous Doctor summarizes his life and the show’s tone well when he insists that he’s serious “about what I do … not necessarily the way I do it.”

While often categorized as science fiction, Doctor Who’s strong, mystical death motif puts it in the grand tradition of fairy tales like The Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter. Like those stories, it grounds its myth in the eccentricities of British culture; avoids tongue-in-cheek, Monty Pythonesque deconstruction; and flourishes as an engine for “reenchantment.” Whether its success will continue will depend on its recapturing that original vision of the show’s meaning, a vision that has grown very muddled over time.

Death is most obviously present in the show’s iconic plot device: the “regeneration” of the Doctor. As Capaldi explained, “The central character dies. And I think that is one of [the show’s] most potent mysteries. Because … that is what happens in life: you have loved ones—and then they go—but you must carry on.”

This “mystery” came about by happy chance. As small Peter in Glasgow was falling in love with Doctor Who in the ’60s, the BBC showrunners were facing a commercial dilemma. The show was a hit—“Dalekmania,” an obsession with the show’s “pepper pot” space Nazi villains, had swept the nation—but their leading man was so ill he couldn’t remember his lines. Writers had worked around it, eventually weaving William Hartnell’s line fluffs into his character. “Chatterton?” he’d distractedly ask, bungling the surname of his companion, Ian Chesterton (who, yes, was named for G.K.).

But the solution was unsustainable. They knew they had to write Hartnell out. But how could Doctor Who exist with no Doctor?

In a way, that is the big question at the heart of every long-running franchise. Every TV show faces an essential problem of structure: the need to create finitude within an essentially infinite format. “Infinite storytelling” requires, as Stan Lee used to say of comic books, “the illusion of change.” Yet for a story to tackle the big questions, it has to have death—true change, not illusions. As the Doctor says at one point, “You need a good death. Without death, there’d only be comedies. Dying gives us size.” Sitcoms stay small, unreal, petty in their concerns. Frasier Crane doesn’t contemplate eternity, just the logistics of a perfect dinner party.

Yet eternity, death, and change are all at the heart of Doctor Who, and that’s because it created an illusion of change like no other: the device dreamed up to solve William Hartnell’s foggy memory. It all came about because someone asked the right question. If the Doctor was an alien, why couldn’t he be a shape-shifter, too? Then he could be canonically recast and possess a true in-universe reason to have a different face.

And then they had the billion-dollar idea, defying every corporate instinct to play it safe. What if the Doctor shape-shifted, “regenerated,” into an actor who looked and acted nothing like the previous character?

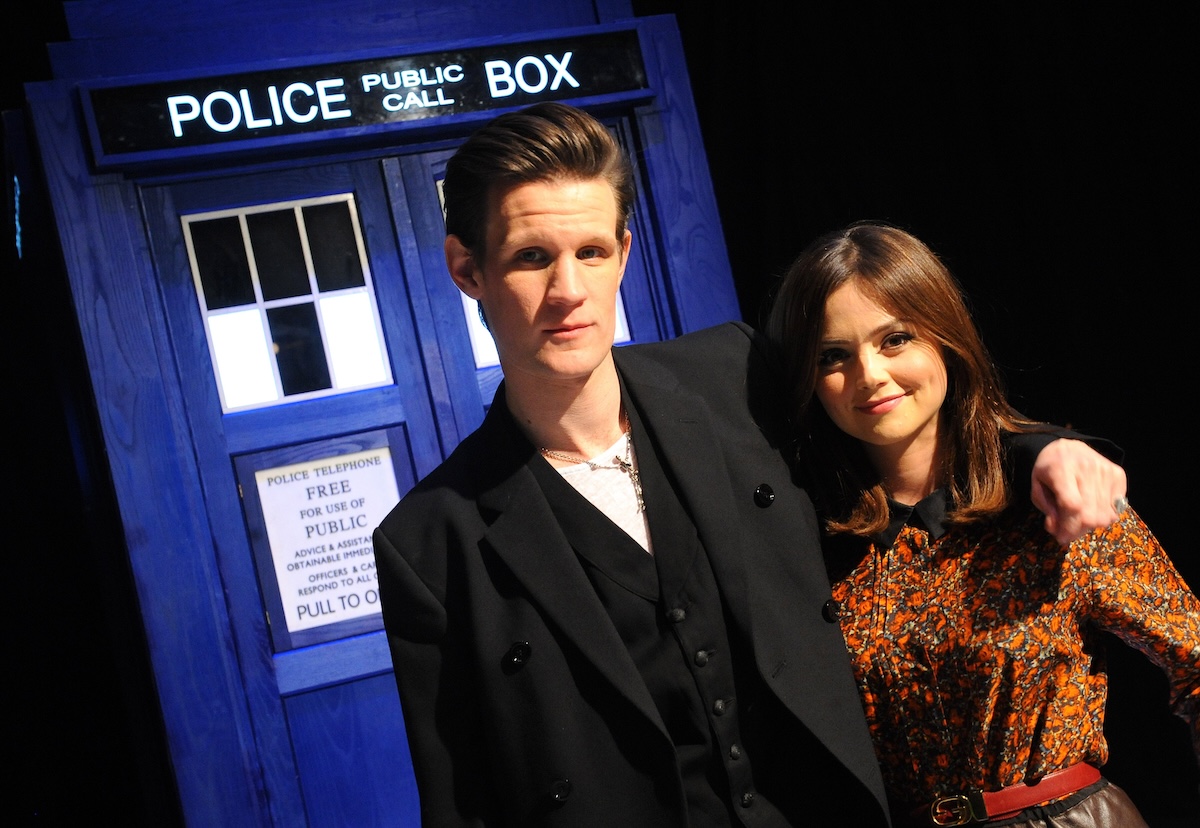

With that they created a convention that has become a ritual these many decades later. On a practical level, regeneration means the show gets a creative shot in the arm every few years, swapping out its main cast and tone. Romantic man-child David Tennant; wild-haired Tom Baker and his 13-foot scarf; Machiavellian professor Sylvester McCoy. A handful of common traits make all these men feel like “the Doctor” but each one is his own man (and once or twice, a woman).

On a theoretical level, regeneration solved the most essential problem of infinite storytelling. When an actor leaves, it feels like a true ending, even as the ritualistic and connective tissue of the setting and premise make the next Doctor part of the same story. Infinite, and yet finite, storytelling. It’s brilliant. At the least, regeneration is a reflection of how “we all change, when you think about it; we’re all different people all through our lives,” and at the most, it’s a powerful moment of resignation to loss of self, “burning the old me to make a new one.” Regeneration is both choosing to keep living and choosing to keep dying, a rich paradoxical metaphor for existence.

Dreamed up as an educational program for children, Doctor Who would evolve into a national and international phenomenon (as of this year, its 60th anniversary, the show is now being distributed globally by Disney+, though older seasons are on HBO Max and Britbox). It’s nearly impossible to jump in without a watch guide.

To many Americans, it may seem impenetrably British—eccentric, child-like, earnest. But while its preoccupation with death gives it a sort of universal mythic appeal, a significant part of its charm is exactly that cultural specificity and lack of irony.

“Let’s be frank, Gallifrey [where the Doctor is from] is an English planet. There is something peculiarly English about the Doctor,” Stephen Fry said of the show. “A tiny bit of Sherlock Holmes … Father Brown, in terms of naive wisdom. There are all kinds of things drawn on for the character of the Doctor that I think in a sense are the best sides of the English character. Not the arrogance, not too much of the misery, not too much of the vanity, not too much of the false modesty, I think that’s what we look for in the Gallifreyan.”

This explains why the Doctor is allowed to be high-handed about the rules of time. Perhaps he has some sense of an underlying moral structure to the universe, but it’s just as likely that this structure has been granted legitimacy by the power of his own people, a race styled like late-medieval aristocrats in escoffions and Catholic vestments. At one point, they entrap him in a massive puzzle box designed to elicit his “confession.” Given this pedigree, the Doctor is a space colonialist, as much as he likes to deny it. Paul McGann, who played the Eighth Doctor and is a history buff in real life, understands the cultural resonance of the Doctor as a stand-in for a traveling Brit. “The First Doctor, of course, was very Victorian,” McGann told me. “If you don’t know, it’s not important, but if you do …”

The show is split into two halves—the old show, of 27 seasons, which meandered into camp and was canceled in 1987—and the revived one, shooting onto TV in a blaze of Buffy-esque, leather-jacketed glory in 2003. (Being a fan of the older show lowers the barrier to entry to meeting key figures in real life. I once found myself in a fight about climate change with Sylvester McCoy in a hotel parking lot, and on another occasion, chatting with Michael Jayston, on his cigarette break, about his days in the RSC with Paul Scofield and Laurence Olivier.)

McGann starred in a failed TV pilot in 1996, the height of “the wilderness years,” but it’s testament to the generosity and flexibility of the story’s fan base and world that he’s always been considered “canon” thanks in part to fan-produced audio dramas (many of which are terrific, for the record).

One benefit of this is that he escaped the show’s usually half-baked special effects. “Doctor Who is a corkingly brilliant idea,” said future showrunner Steven Moffat in 1995. “The actual structure, the actual format is as good as anything that’s ever been done … so good it can even stand being done not terribly well—as one has to concede it [has been] done.”

That’s where childlike earnestness comes in. To sell a decent adventure yarn on a shoestring TV budget demands that actors perform with absolute conviction.

“We all laughed at the fact that you could read the newsprint on the papier-mâché monsters,” Fry continued, but “if it gets self-knowing, if it gets arch, if it gets self-referential, it’s destroyed. The beauty of Doctor Who was its innocence—it didn’t make fun of itself too much.”

Consider: Tom Baker was working on a construction site when he was cast in the role. He, too, noted the show’s guilelessness and had a personal explanation for why he could commit to it so fully. “My response to it was just childlike,” Baker said. “I was brought up in a very religious background. Roman Catholic Liverpool. And so I was able to believe in fantastic things, guardian angels and voices and powerful beings watching over us and miracles and all that sort of thing. … I was able to quite accept it all and not do a tongue-in-cheek send-up or whatever.”

Perhaps that’s why playing the Doctor is more than simply being the lead in a TV program. In British culture, it’s a significant cultural ambassadorship. Meeting the Doctor in the street is different than seeing Sean Connery shopping. Connery isn’t James Bond; he’s a celebrity. Meeting the Doctor in person is like running into Santa Claus or Gandalf down the pub. Capaldi, famous for playing foul-mouthed Malcolm Tucker in The Thick of It, swore off swearing in public for his four-year tenure.

The day after Baker’s first episode as the Doctor aired, people were saying hello in the street. At children’s hospitals, they even asked him to see children in comas—perhaps the Doctor might make a difference. Forty years later, the octogenarian actor still takes selfies in the supermarket.

Death, culture, and innocence, then, are key tropes at the heart of Doctor Who’s success. But there’s another one, and it’s vital. After regeneration, the next most brilliant device in the story is the Doctor’s spaceship, the TARDIS—a 1950s British police box (“the chameleon circuit” got stuck) that, much like C.S. Lewis’ wardrobe, contains an entire world within its ordinary exterior. It can go “anywhere, anywhen.” It’s in a state of temporal grace—“you’re safe in here, and you always will be”—except when it tries to kill you. It’s good, but never safe.

Lewis—who died the day before the first episode of Doctor Who aired—would probably have been happy to know that a stray phrase in The Last Battle, envisioning a stable “bigger on the inside,” would eternally live on as a description of the Doctor’s ship.

The idea itself, of a wondrous passageway in a banal setting, pops up all throughout the countercultural literary movementof the mid-20th century, from the subtle hints of Evelyn Waugh’s “low door in the wall … which opened on an enclosed and enchanted garden, which was somewhere, not overlooked by any window, in the heart of that grey city” to T.S. Eliot’s “the door we never opened / into the rose-garden.”

Most fantastical of all is J.R.R. Tolkien’s “round the corner there may wait / A new road or a secret gate / And though I oft have passed them by / A day will come at last when I / Shall take the hidden paths that run / West of the Moon, East of the Sun.”

Placing the ordinary and the extraordinary cheek by jowl is the very purpose of fantasy. It’s hard to get more familiar than shop mannequins, stone statues, shadowy corners, and the space underneath the bed. In Doctor Who, each one of those things is a monster.

If big ideas start in high culture before filtering down to everything else, then Doctor Who should be seen as a small victory for that movement’s fantastical hope. Lewis, of course, thought this literary effect reflected a Christian truth—that the world really was magical and charged with supernatural grandeur.

Doctor Who isn’t so certain, even though as a British show it can hardly help recycling concepts inculcated in chapels for a thousand years. Moffat has made the point that as a mass appeal program, and a British institution, Doctor Who can’t truly be left- or right-wing. In similar fashion, the Doctor is both a passionate anti-theist and a Jesus figure, and the show varies from screeds against blind faith to a haunting hymn sung by millions stuck in hovercar traffic for decades.

Its persistent sense of exile is perhaps the most religious thing about it. That strong sense of almost existential homesickness and hope pervades the 60 years of the show, and despite its increasing embrace of secular humanism—it’s little wonder that Tom Baker’s costar and briefly wife, after divorcing him, would go on to marry Richard Dawkins—this hopeful mystical spirit will not be eradicated. “I am and always will be the optimist,” the Doctor declares. “The hoper of far-flung hopes and the dreamer of improbable dreams.”

Lewis thought such literary devices were powerful expressions of an emotion the Germans called sehnsucht:

That unnameable something, desire for which pierces us like a rapier at the smell of bonfire, the sound of wild ducks flying overhead, the title of The Well at the World’s End, the opening lines of Kubla Khan, the morning cobwebs in late summer, or the noise of falling waves.

There’s a distinct echo of his words in the first Doctor Who serial, penned by an Australian writer who was also a Catholic lay preacher. “If you could touch the alien sand and hear the cries of strange birds, and watch them wheel in another sky, would that satisfy you?” asks the Doctor, an impish and enigmatic stranger, putting the skepticism of two ordinary humans to the test. “Have you ever thought what it’s like to be wanderers in the fourth dimension? Have you? To be exiles?”

The Doctor is haunted by the transience of everything around him. “I’m not a human being; I walk in eternity,” he complains in the midst of a midlife crisis (he’s about 750 at the time). And later, “Planets come and go. Stars perish. Matter disperses, coalesces, forms into other patterns, other worlds. Nothing can be eternal.”

It’s down to his companions, who vary from a bleached-blonde shop cashier to an 18th-century Highlander to an Australian flight attendant, to anchor him to the quotidian rhythms of life and to his own moral obligations: “Be a Doctor—never cruel or cowardly.” They rebuke his hubris and in their frailty—in their un-protect-ability—remind him that he can’t be God.

“Everything has its time and everything ends,” the Doctor declared as his credo in the show’s 2005 revival. In order to accomplish a soft reboot, the showrunner Russell T. Davies reimagined the character as the survivor of an intergalactic war, the last of his kind. He scorns ordinary people for not recognizing “there’s a war going on” underneath the skin of their petty bourgeois lives. That could sound like revolutionary rhetoric (and in the more politically explicit episodes, it is), but from his tone, it’s more like the ending of the book of Daniel. There’s an entirely other dimension to the world around us that we are too materialist to see.

There’s an important exception to the death motif, though: death comes in its time, and not before. The wonders and terrors of the universe should, paradoxically, inspire a particular value for things small and “unimportant.” I’ve argued that Doctor Who has been the most pro-life show on TV for years, holistically, philosophically, and (despite its protestations to the contrary) as a narrow policy matter. “It’s a little baby,” a woman protests in a 2014 episode, a rather silly allegory where characters must decide whether to kill an unhatched space dragon threatening the earth. “An innocent life versus the future of all mankind.”

The Doctor’s companion ends up sparing the life of a baby, creating a ripple effect in the future that ensures humanity “will endure till the end of time … [because] it looked out there into the blackness and it saw something beautiful, something wonderful, that for once it didn’t want to destroy. And in that one moment, the whole course of history was changed.” (The show really does enjoy the English language, with Douglas Adams and Neil Gaiman contributing as notable guest writers—Gaiman’s The Doctor’s Wife is one of the great philosophical glosses on the show’s central tropes.)

“An ordinary man … that’s the most important thing in creation,” the Doctor exclaims in one story, explaining why they can’t save the life of an “insignificant” person in the past without upending history. “The whole world’s different because he’s alive.” The show exhibits a remarkably consistent ethos around life—a sort of semi-Christian humanism. The Doctor gets to define his own rules of time, but they’re very often consistent with a (perhaps pompously) righteous defense of imago Dei.

“There’s no such thing as an ordinary human,” is a line from the show that feels like a slight rewording of C.S. Lewis’ “you’ve never met a mere mortal.” (“I like that [quote],” McGann commented. “The best of it wears it lightly, but it’s there. You don’t want it to get too aphoristic.”)

Putting this principle in peril, however, has meant that the show itself is in desperate straits. As the trendy transhumanistic principles of the day took hold, near the end of the Moffat years, the story trickled into a moving but conflicted tragedy. A young woman whose body has been made unrecognizable by evil robots despairingly lamented, “I don’t want to live if I can’t be me anymore.” Distressingly, the Doctor, who once told a suicidal man that “there is, surprisingly, always hope,”mutely accepts that his companion doesn’t want to carry on. Perhaps it’s her time. Perhaps it’s his. When Peter Capaldi staggered into the TARDIS for his last farewell before regeneration, it was with the ambivalence of an old man and an aged show, and in other areas of the plot Moffat leaned heavily into his favorite trope to avoid the tangibility of death: a sort of techno-resurrection, totally disembodied.

The episode’s philosophical ennui, transhumanism, and weak resistance to despair presaged the coming troubles. In 2017, the first female Doctor entered the TARDIS, to much applause and little success. Craft problems were at the forefront—showrunner Chris Chibnall’s writing is far staler and blander than that of previous eras. The genderswap is handled without any intelligent consideration of how gender affects archetypes. But it’s more than the fact that gender-flipping Gandalf doesn’t work unless you replace him with, say, Minerva McGonagall (they didn’t); it’s the fact that the writers also eliminated cultural specificity (it’s distinctly less British, and they replaced Christmas specials with New Year’s Day specials), and discarded a significant portion of the show’s mystery, undermining its sehnsucht to disastrous effect.

In a way, switching the yearly special from Christmas, full of cozy indoor traditions, history, and evocative myth, to New Year’s Day, a weightless faux-holiday, encapsulates the lack of vision at the heart of the Chibnall era. Jodie Whittaker is a lovely actress, but her concept of the Doctor, so safe and sterile and genderless, barely feels like a real human being, never mind a “real alien,” from the English planet of Gallifrey.

All is not lost. I’m hesitantly optimistic for the future. Russell T. Davies, who rebooted the show in 2003, is returning for 60th anniversary celebrations, bringing back a popular earlier Doctor, and starting a new era of the show that will air on Disney+. Davies always had a strong sense of the unavoidable nature of death, keeping his stories grounded in tragedy (ideally, we may get more Moffat-penned stories under Davies’ editing, for Davies’ groundedness tempered the transhumanism, making for astonishingly bittersweet eucatastrophes in The Empty Child, The Girl in the Fireplace, Blink,and Silence in the Library).

“The value of myth,” C.S. Lewis wrote in an essay defending The Lord of the Rings, “is that it takes all the things we know and restores to them the rich significance which has been hidden by ‘the veil of familiarity.’”

We can only hope that Doctor Who’s vivid humanism, and its echoes of Christian resurrection, will prevail, because it’s one of the great “reenchantment” stories of our age, reminding us to always look askance at statues, for they may be monsters, or at holes in the wall that may lead to another dimension. It reminds us that we live in a universe that is ultimately so much bigger on the inside, like Aslan’s country unfolding endlessly before us. For indeed, we do.