As the producers of the venerable James Bond franchise come to ponder how best to refurbish their hero for the uncertain times ahead—a woman, perhaps, and/or a person of color?—a small but persistent debate among film buffs continues to address the chicken-and-egg dilemma of which came first: Have the actors successively playing Bond over the past 60-plus years consciously fine-tuned their performance in response to all the eddies in fashion and culture, or have they been ahead of the curve in defining the limits of an acceptable sort of male behavior for the rest of us to emulate? Is it us who have changed, in other words, or Bond?

The answer would seem to be: a bit of both. Bond has done nothing if not mirror his times. When Dr. No was released in 1962, there was still an entity called the British Empire, and the phrase “stiff upper lip” could be—and was—used without satire to describe such highly prized qualities as stoicism, irony, and understated self-confidence that the character epitomized. He’s survived to see a time of lost certainties, gender fluidity, and a class structure so discredited (at least in Britain) that to dare speak in anything like an “educated” accent is widely regarded as a form of professional suicide. That Bond’s most recent outing, 2021’s No Time to Die, proceeds in a pervasive atmosphere of melancholy and regret, with a cast of notably tough-minded women performing not only the standard decorative roles but also many of the athleticized action sequences, perhaps tells its own story of the franchise’s evolution from the era of Sean Connery to that of Daniel Craig and beyond.

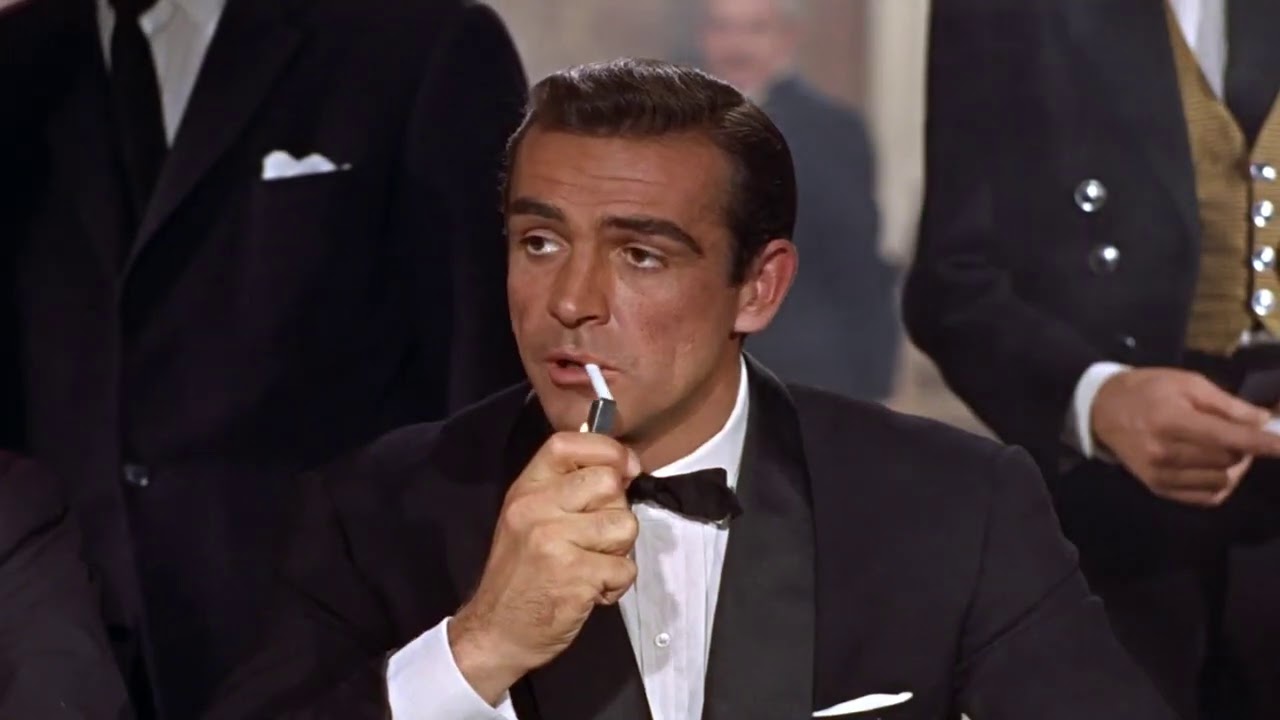

Rex Harrison, David Niven, Trevor Howard, Cary Grant, Patrick McGoohan, Laurence Olivier, Stewart Granger, James Mason, Richard Burton, and a young Michael Gambon (the last of whom was told, a trifle uncharitably, “Your teeth are bad, and you have breasts”): Those were just some of the names under consideration around 1961–62 for the then deeply unpromising role of Sir James Bond, the British Secret Intelligence Service agent created by a wealthy, vodka-quaffing former Royal Navy officer turned journalist named Ian Fleming. Rather belying the lavish sets and glamorous international locales of later Bond films, everything was initially to be done on a shoestring. Harrison, Niven, and Burton all turned down the title role because of its salary, $25,000 (or $400,000 in today’s money) for a six-month shoot, and the other names were also rejected for one reason or another. Things remained at a standstill until one of the film’s producers, Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, and his wife, Dana, wandered into a sparsely attended screening of Darby O’Gill and the Little People, a Disney whimsy about an Irish caretaker who spins so many tales that no one believes him when he announces he’s befriended the King of the Leprechauns. Playing third banana to the caretaker and the leprechaun was a 30-year-old, balding, Scots-born former Mr. Universe contestant named Thomas Sean Connery. “There,” Dana Broccoli informed her husband, “is your Bond.”

You can see why the only fitfully employed Connery jumped at the role. Apart from the money, which improved with each successive film to the point where he was earning a flat fee of $500,000 ($8 million today) and a percentage of the profits, it was a genuine artistic stretch. As envisaged by Fleming, the character was an impulsive, imperfect, occasionally sadistic mess, and Connery knew that general territory well enough to find the sympathetic center within. Also, he got to display a nice touch of emotional restraint as well as the trademark athleticism, and at least in the early films the gadgetry hadn’t yet stylized the whole franchise to the point of self-parody. Perhaps Connery’s greatest asset was that he lacked an established screen image, allowing him to create the template for the cinematic Bond, against which audiences judged his successors.

These things are necessarily subjective, but I have always felt that 1964’s Goldfinger was the early Bond’s finest hour. Brusque, sarcastic, and virile with his cropped hair, swaggering gait, and ad-libbed one-liners, Connery brings just the right mixture of humor and menace to the proceedings. Of course, it’s a preposterous plot, with its most durable takeaway images those of a semi-nude young woman killed by being daubed with gold paint, a mute Korean assassin with an unusually lethal bowler hat, an all-female flying circus spraying nerve gas over the U.S. gold bullion depository at Fort Knox, and a laser beam pointed at that part of the hero’s lower anatomy most required for his continued success as a serial womanizer. You could never get away with it today, at least with a halfway straight face, and perhaps that’s precisely its charm. If some destructive process were to eliminate all we now know of the Bond franchise, only Goldfinger remaining, we could surely reconstruct from it every outline of the basic formula, every essential character and flavor contributing to the series we still flock to a little more than 60 years later. Of the six successive Bonds, Connery’s is not only the most emblematic of his times, but the one who could stand as a surrogate for all the others who followed.

There was little of what Fleming called the “cold and ruthless” side of his creature in Roger Moore’s depiction of the role beginning with 1973’s Live and Let Die. Moore was an actor of considerable charm, if limited professional range. A critic once remarked archly, but not wholly unjustly, that Moore had apparently realized at an early age that the act of “raising his right eyebrow and turning his left profile to the camera is all that is required of him.” Moore had a gift for deadpan comedy and for delivering a punchline with an entertainingly wry grin, but one looked in vain for any sign of Connery’s latent sadism. There was also the fact that the Ivanhoe and Maverick alumnus was 46 when he inherited the role, while Bond was supposed to be in his early 30s. Perhaps it didn’t matter so much in the early films, but the embarrassment of his seventh and final outing, 1985’s A View to a Kill, made a compelling argument for a mandatory retirement age. It was a poignant way for Moore to bow out, and unlike Connery’s unlicensed return in Never Say Never Again, which at least had the wit to make a theme of its star’s physical decline, A View to a Kill never knowingly acknowledged the problem. We were just supposed to take the character at face value, the studio insisted, which might have been fine so far as it went but for the unfortunate fact that Moore’s recent facelift had given him the pie-eyed blankness of a zombie.

I can say all this because I happened to be one of the lowly flacks then working in the galley ship of the United Artists press department and played some small role in promoting A View to a Kill. In my experience, the film’s star was never less than charming, and I remember strolling around Pinewood Studios with him one glorious early summer evening, with Moore inhaling a vast cigar and pointing out the 007 soundstage that had just reopened after mysteriously burning to the ground the year before. “Perhaps it was an omen,” he admitted, giving the signature twitch of his eyebrow, before revealing that he had first wanted to walk away from the role several years earlier. In retrospect, Moore was the perfect man for the job in the winking, ironic days of the early 1980s, an actor who underlined the absurdity of Bond himself. “You can’t be a real spy and have everybody in the world know what you drink,” he told me with a characteristic smirk. “If you think about it, it’s just hysterically funny.”

“Connery played Bond as a killer and I played Bond as a lover,” Moore once said. Only on Fridays did he resemble his cold-blooded predecessor. “That’s the day I received my paychecks.”

The two-film reign of the Shakespearean-trained Timothy Dalton in the late 1980s in turn caught something of that transitionary era. It’s of course almost always a mistake to try and assemble random historical facts into a neatly unified pattern few people would have recognized at the time, but with hindsight it’s fair to say that the age of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher was one associated with a certain go-ahead conviction, and the period that followed their departure one of retrenchment and rethinking, in which to one extent or another we all became slaves to the computer. Dalton himself expressed some of this evolution in his role as Bond, reflecting: “I didn’t want to make him a superman. You can’t identify with that … I wanted to capture the occasional sense of vulnerability, and I wanted to make him human.”

It’s a curious footnote to the Bond franchise that a character whom his creator described as the “quintessential Englishman” was successively played by actors of almost every other nationality. Connery was proudly Scottish; his short-lived successor George Lazenby—with a single turn in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service—Australian; Moore was of Anglo-Indian stock; and Dalton, Welsh. The protean spirit of the times again seems to have pervaded the role when it came to the turn of Pierce Brosnan, an Irishman, to order the shaken martini. “I felt I was caught in a time warp between Sean and Roger,” he’s said. “It was a hard one to grasp the meaning of. The violence was never real, the brute force of the man was never palpable. It was all too tame, and the characterization didn’t have a follow-through of reality. It was a superficial, fin-de-siècle sort of Bond.” All four of Brosnan’s outings were nonetheless commercially successful, even the poorly reviewed Die Another Day, with its invisible cars and cameo by Madonna.

Which brings us to the late reign of Daniel Craig, with his engaging bat ears and chiseled boxer’s face flecked with the scars of some previous dust-up, who gave us a Bond for the 21st century: mentally and physically jaded, self-aware, offering a bit of escapist fantasy for a Britain that doesn’t count for as much as it used to, and some old-fashioned macho swagger, with redeeming moments of introspection, for the rest of the world. Again, it’s subjective, but many of us would nominate 2012’s Skyfall as Craig’s shining hour. He starts proceedings already impressively bruised and battered, goes through the first 40 minutes unshaven, and yet, when the moment comes, gloriously rises to the challenge of the sort of absurd stunts and chases through crowded Middle Eastern bazaars (involving no less than three Fruit Cart Scenes) we’ve come to expect of the character. But this is a new century, and the most conspicuous “Bond Girl” on display isn’t some bikini-clad strumpet but the austere, dominatrix figure of Dame Judi Dench as an unsmiling M, the head of British Secret Intelligence. There’s even a psychological subtext to suit the sexually confused age, with a backstory alluding to Bond’s troubled childhood and the archvillain’s tendency to pointedly call M “Mother” in front of his opponent. The general consensus was that Craig did an estimable job in updating the character for the times, although by a great piece of luck I happened to find myself at the same table as Sean Connery at an awards dinner in London in 2006, when someone asked him what he thought of the latest pretender to his throne. The same terse qualities that made the Scotsman so compelling on screen were deployed to good effect here.

“Daniel’s good,” Connery allowed in his familiar sonic boom. And as for the then newly released Casino Royale? “Half an hour too long,” he said, in a way that precluded any further discussion. “And the music was crap.”