Birth rates are in free fall across the Western world, spurred along by a complex web of factors, from increases in economic prosperity and egalitarianism to declines in religiosity to idols of choice and convenience. Whatever the reasons, family has taken a back seat in the hearts and minds of many.

“Most of today’s Americans believe that educational and economic accomplishments are extremely important milestones of adulthood,” according to a recent study by the U.S. Census Bureau. “In contrast, marriage and parenthood rank low: over half of Americans believe that marrying and having children are not very important in order to become an adult.”

Or, as W. Bradford Wilcox once put it: “Culturally, young adults have increasingly come to see marriage as a ‘capstone’ rather than a ‘cornerstone’ – that is, something they do after they have all their other ducks in a row, rather than a foundation for launching into adulthood and parenthood.”

In a new report from the Institute for Family Studies, More Work, Fewer Babies, researchers Laurie DeRose and Lyman Stone dig deeper in this same area, exploring the rising prominence of “workism” in modern life and its role in declining fertility rates around the world.

“People’s attitudes toward work – specifically the elevation of career advancement to a very high place in individual values – may influence fertility,” they write. “The rise of ‘work-focused’ value sets and life courses means that achieving work-family balance isn’t just about employment norms adjusting to the growing complexity of individual aspirations; it can also mean that many men and women find their preferred balance to be more work and less family.”

In our increasingly secular age – wherein “traditional” belief systems are being rapidly replaced by a series of “new atheisms” – a healthy recognition economic “meaning making” can often turn into a base idolatry of the work itself. Derek Thompson recently explored this trend in The Atlantic, defining “workism” as “work as a kind of religion, promising identity, transcendence, and community.” “Everybody worships something,” he writes, and “workism is among the most potent of the new religions competing for congregants.”

Our economic activity brings plenty of meaning, of course. But when it becomes over-elevated as a god above all else, we risk a society that is both one-dimensional and unsustainable – lacking a foundation of family and the sort of institutional life that fosters a free and virtuous society.

Using data from World Values Survey and European Values Survey, DeRose and Stone observe these shifting preferences about family and work, as well as how various dispositions “interact with gender role attitudes to influence national- and individual-level fertility outcomes across numerous societies and time periods.”

Their conclusion: The more “workism” that exists in a high-income country, the larger the decline in fertility is likely to be. More specifically, the study finds that:

• Highly work-focused values and social attitudes among both men and women are strongly associated with lower birth rates in wealthy countries.

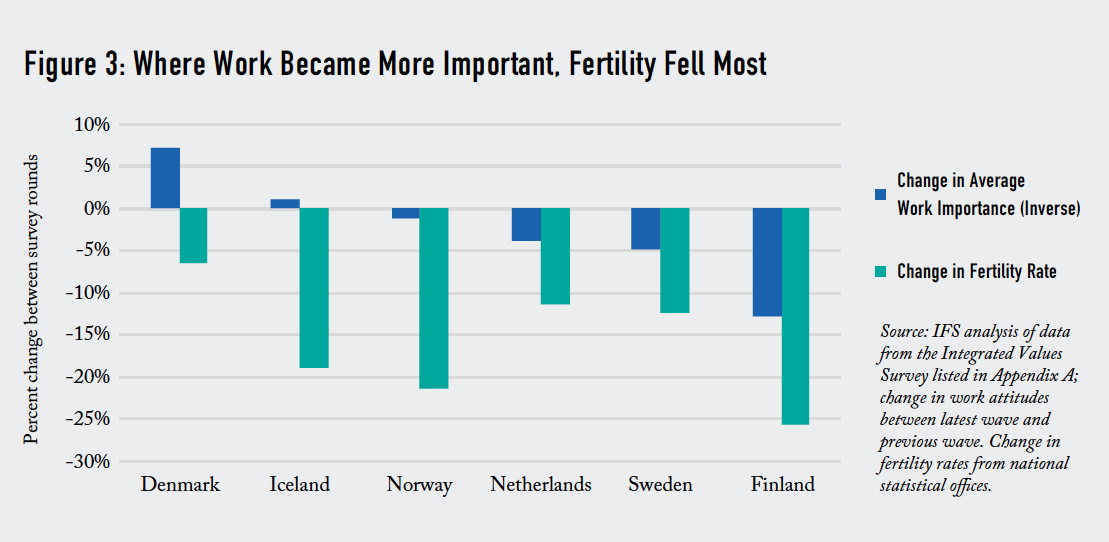

• The decline in birth rates over the last decade across many high-income countries—including some Nordic countries—can be partly explained by the rising importance individuals assign to work as a source of value and meaning in life.

• Government policies that try to increase fertility by providing more benefits aimed at workers, such as universal child care or parental leave programs, may undermine their efforts as they strengthen a “workist” life-script rather than a “familist” one.

These findings are particularly striking when the authors observe Nordic countries, which have (up until now) served as some of the shinier examples of fertility amid “welfare-state” capitalism. Such countries are routinely praised as case studies in modernity done right – egalitarian values, lavish welfare programs, and (somehow) relative prosperity. Lately, however, they have experienced drastic declines in fertility, despite their treasure troves of “pro-family” government benefits.

“What could possibly explain such a large, decade-long decline in fertility to historically unprecedented lows,” the authors ask, “…even in societies that support childbearing through generous policy supports, and where gender egalitarian values have progressed further than anywhere else in the world?”

As demonstrated by the following chart, “workism” appears to play a role:

“We suggest that part of the answer relates to a previously under-studied social force: the changing social, moral, and even ideological place of market labor in the life course,” they write. “As social values change over time, some wealthy countries with highly individualist and egalitarian values have also begun to adopt a new values-based emphasis on work and career success as a key source of meaning and value in life, which may compete with family goals.”

Such findings highlight key tensions between “workism” and “familism,” as well as some of the key pitfalls we ought to avoid, whether in our cultural catechesis or policymaking:

If the value placed on family – which we refer to as familism –supports procreation, more familistic people could desire to have more children, be more persistent when facing obstacles to having more children, or both. Societies where familistic values are more common would share these fertility advantages.

In contrast, placing a high degree of value on work can dampen fertility desires and make them less likely to be realized: workist individuals would be expected to have fewer children, and societies where workism is common would have low fertility reinforced by prevailing norms…The desire for meaningful or important work, not simply well-compensated work, is powerful, and has significant and negative implications for childbearing.

Unfortunately, as politicians continue to promote various approaches to “pro-family policy,” each seem tilted toward maintaining our status quo of workism – offering surface-level child-rearing “perks” to prod parents into getting back to their economic commitments.

If we neglect the role of incentives (not to mention the underlying cultural forces), such policies can easily work against their supposed goals. Insofar as any supposed benefits make it easier to work and have children, they can simply reinforce the same lopsided career-mindedness that led us here in the first place. For example, DeRosa and Stone note that many of these approaches are likely to shuffle more women out of the home and into the workplace with little thought about incentives for men (or the subsequent impact on children).

“A better path to gender egalitarianism – particularly in countries with highly inflexible and two-tiered labor markets like South Korea or Italy – would be to enable men to work less, rather than seek means for women to work more,” the authors explain. “This is especially important, since in many very low-fertility countries like Japan and Korea…men do not have a large excess of free time for leisure compared to women, suggesting that the problem is work per se, not the intra-household division of that work.”

Likewise, particularly in the American context, we see constant pushes to expand publicly funded child care, rather than offering parents more flexibility in the home and workplace:

The dynamics we describe here may help explain why most empirical studies have found that cash allowances increase fertility rates by more per public dollar spent than funding for child care. Cash allowances allow families to reduce work, whereas universal child care policies normalize work-focused family models even more.

More generally, encouraging more flexible work arrangements, rolling back strict licensure and certification rules for work, and tackling “salaryman” norms could all be beneficial pro-natal strategies—not because they would give women greater equality at home and work (although they certainly would), but because they would facilitate reprioritization of family life over work life for all parents.

Do we truly value family and children? If so, our attitudes ought to align accordingly, rather than reorganizing our incentives to simply preserve or protect those external quests for meaning.

Given the evidence thus far, we ought to have plenty of skepticism about the ability of “pro-family policy” to boost fertility rates or realign our cultural attitudes. Indeed, as DeRose and Stone indicate, it is likely to make things worse.

When facing the monsters of modernity, we will need far more than the designs of man. It will require a renewed appreciation for the family, yes. But it will also require a renewed rejection of ourselves and the idols to work and career that we’ve come to construct – reimagining “vocation” from being an idol of self-actualization to a means of crucifixion.

If we are really looking for “meaning,” there’s plenty more to be found.