Could economics, which academics long ago deemed “the dismal science,” have a specifically Christian application? If so, what are the unique features of a Christian approach to economics?

Edd S. Noell of Westmont College and Stephen L. S. Smith of Hope College expertly answer this question in a recent study published in Christian Scholars Review titled “Economics, Theology, and a Case for Economic Growth: An Assessment of Recent Critiques.” (The authors gratefully acknowledged the financial support of their current colleges, Smith’s former institution of Gordon College, “and of a 2014 Acton Institute Mini-Grant.”)

The article aims to begin “a comprehensive treatment of the economic and moral case for growth that responds to modern moral and Christian theological objections.” The authors defend GDP growth from common religious objections, including charges that the free market causes environmental degradation and hyperstimulates greed. “A number of largely overlooked dimensions of these notions distinguish the Christian case for economic growth from secular claims,” they write. While Milton Friedman pointed out broader social toleration and Paul Collier said low growth fueled political instability in the developing world, Noell and Smith discuss three closely related elements that define a uniquely Christian view of economics – and which underscore the importance of economic growth:

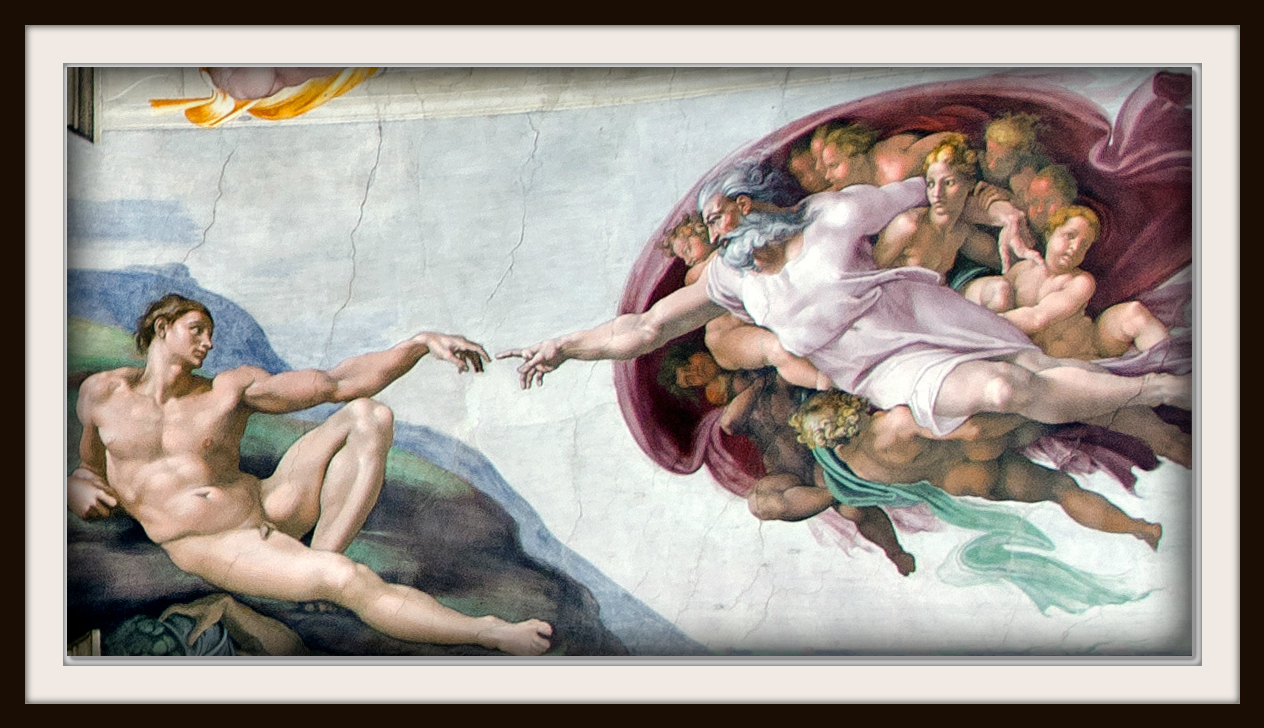

1. Creativity and work. God the Creator tasked human beings with labor even in the Garden of Eden. This work allows us to refine, purify, and fructify His handiwork. While this does not make human beings co-creators – for only God created all things ex nihilo – it gives us a canvas on which to display the creativity God implanted inside all His children. “Humans are to represent God’s rule over the world by being God’s vice-regents. They do so in acting creatively – as God was and is creative – and their labor and rest have dignity attached to them because God, too, labored and rested,” they write. “While God is the ultimate owner of creation, humans made in his image are given the ‘creation mandate to fill the earth and bring forth its bounty while maintaining care for the earth as stewards responsible to the Creator.”

2. Wisdom and prudence (practical wisdom). Not only must human beings apply their gifts creatively, but they must also learn how best to multiply their efforts. They do this by taking stock of their talents and resources, surveying market conditions, and acting at the best possible moment. Wisdom is widely diffused, leading to diversification of knowledge, skill, and productive capabilities. Trade “is the key to the society-wide sharing of the fruits of specialization; without trade, the benefits of specialization and creative work in specific areas of life cannot be sustained.”

3. The image of God (Imago Dei) reflected in each person. The creativity within each person, and the prudence required to executive it, flow from the fact that each individual human being has been created in the image and likeness of God. Unlike ancient mystery religions, this innate human dignity extends, not merely to the ruler, but to every person. This means that creativity and growth are not the exclusive provinces of any one caste, class, or clique but the universal and eternal reality of the entire people. “The fact that human creativity is a sign of God’s image in us, and is the proximate source of economic growth, has a further implication. Creativity is free and inexhaustible. Therefore economic growth can proceed, in principle—in the cultural and institutional contexts that allow free rein to creativity—forever,” they write. “Any economic system bears the burden of operating in a world marred by sin, but an economy that facilitates the full expression of our being made in the image of God will invariably exhibit growth.”

“The implications of [these three concepts] for growth have been underappreciated,” they write, “by much of current Christian thinking.” This is particularly true of religious critiques of GDP growth, especially in wealthy nations.

Although support for GDP growth among economists is “close to unanimous,” objections from scholars in the humanities and social sciences has been “withering,” “broad and serious.” This includes blaming prosperity for “contributing to the problems of consumerism, materialism, environmental damage, and income inequality.” Noell and Smith forthrightly defend GDP growth as both an instrumental and an intrinsic good:

It is not in fact self-evident that consumption is a moral problem. It is surely a good thing when poorer countries grow and households can afford to cook their meals with natural gas rather than cow dung, or to send their daughters to school rather than into back-breaking unpaid paddy work. … In Christian theological terms, the growth in material prosperity of the past two-and-a-half centuries is legitimate and good, for richer and poorer countries alike. It should not be given up hastily.

Far from endangering the planet, economic growth is good for environmental stewardship – and vice-versa. As a UN study found, a nation’s likelihood to rank environmental concerns as a priority rises directly with its wealth. Impoverished societies using rudimentary agricultural or building techniques drive deforestation and air pollution. Moreover, those who are condemned to a life of subsistence farming, left wondering where their next meal is coming from, pay scant attention to global chlorofluorocarbon levels. “Wealthy democratic societies have a track record of being willing to design and pay for … innovative, less-polluting products,” the authors note. “[G]rowth generates the resources that pay for environmental care.”

Consumerism and self-indulgence are indeed problems – but they are not problems that emerge uniquely from any one economic system. On the contrary, they come out of the heart. “Critics who hope to reduce greed and materialism by slowing growth and moving away from a market system are misjudging the fundamental sources of these human vices, which would be present in any human system,” Noell and Smith write. Indeed, Pope Leo XIII wrote in December 1878 that socialism is motivated “by the greed of present goods.”

Noell and Smith deserve our profound thanks for helping us understand a Christian approach to the proper stewardship of the world’s goods, a vice-regency that will – that must – include economic progress, innovation, dynamism, creativity, and growth.