In the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 22 million Americans lost their jobs, effectively reversing several years of economic growth. This would mark the beginning of a “two-track recovery” that is increasingly divided between those whose livelihoods remained safe and secure and those whose industries or enterprises have been thoroughly upended.

As governments moved to shut down key sectors of the economy last spring – promoting a series of strange dichotomies about “essential” vs. “non-essential” work – others were bound to benefit. Today, after a swirl of lockdowns, layoffs, “stimulus” checks, relief packages, and full-scale market readjustments, many now see a world wherein scrappy mom-and-pop businesses are doomed to fail as technology giants and big-box retailers continue to soar. Whether due to the blunt force of arbitrary edicts or the inescapable tragedies of circumstance, many workers are at a severe disadvantage.

Seen from a different angle, however, our economic future is not so bleak. Despite the surrounding chaos, the country has also seen an unprecedented rise in entrepreneurship. Pain and destruction still persist, but workers across America have been turning their personal tumult into social abundance, creating new enterprises and institutions that will serve society in fresh and innovative ways.

“The coronavirus destroyed jobs. It also created entrepreneurs,” writes Kim Mackrael in the Wall Street Journal. “To adapt to the pandemic and the job loss it unleashed, more Americans are becoming their own bosses, setting up tiny businesses to work as traveling hair stylists, in-home personal trainers, boutique mask designers and chefs.”

While the relevant data can be hard to capture, we see several strong indications of such a boom. According Mackrael, “Labor Department data show that in October, while nonfarm payroll jobs remained down 6.6% from the pre-pandemic level, what’s called nonfarm unincorporated self employment was recovering faster, down just 2.4%.” Meanwhile, filings for new businesses are on an historic rise, as Eric Boehm explains at Reason:

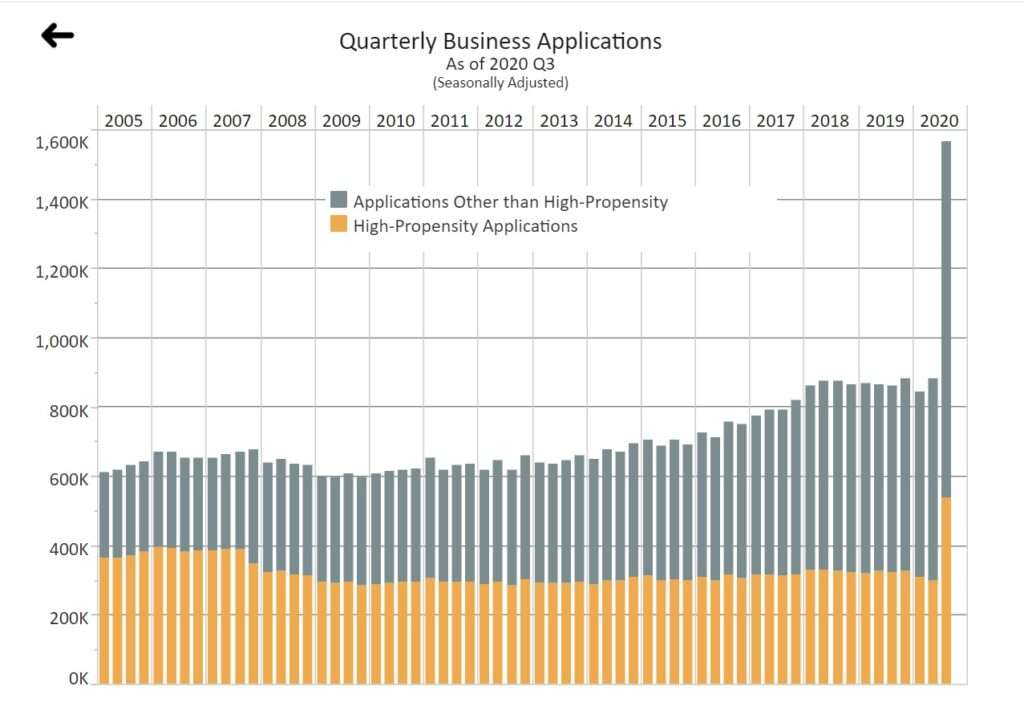

According to data from the Census Bureau, the number of new business applications filed in the United States surged during the third quarter of this year to nearly double the quarterly average of the past decade. The Census Bureau’s data, which are aggregated from various mandatory filings that businesses must make with the IRS in order to obtain a tax identification number, show that more than 1,500,000 business applications were filed between July and September of this year. It’s a dramatic spike in new business applications, which average about 800,000 per quarter and rarely deviate very far in either direction regardless of macroeconomic conditions.

Perhaps even more encouraging is the fact that the number of what the Census Bureau calls “high propensity applications” has shot upward too. Those are businesses that have already surpassed several hurdles in the IRS application process and are deemed to have a “high propensity of turning into businesses with payroll.”

As The Economist reports, these “high-propensity” applications have “recently reached their highest quarterly level on record.” Consider the following graph:

But why? During the financial recession of 2008, this was not the case, with such applications seeing a rapid decline. “Over the past four decades the rate of new-business creation had been drifting downwards,” according to The Economist. “The fact that America has suddenly recovered its entrepreneurial mojo is particularly intriguing, since nothing comparable seems to be happening elsewhere in the rich world.”

Some of it can be explained by recent innovations, such as improved access to digital marketing tools, the continued rise of e-commerce, and increasingly efficient global supply chains. But much of it is likely due to the nature of the crisis itself, which was predicated not on internal financial rumblings, but on outside efforts to slow the spread of the virus. For almost a year, we have been curtailing and adjusting our consumer spending on purpose, whether by personal choice or in accordance with state guidelines.

“A working hypothesis is that individuals realize that the new normal is going to be different from the old normal,” says John Haltiwanger, an economist at the University of Maryland, quoted by Mackrael. New entrepreneurs “are engaging inactivity that is associated with that new structure.”

Unfortunately, despite these key differences, the government’s economic response has been largely the same as in crises of the past: top-down tweaks and arbitrary juicing of the economy that ignores the range of bottom-up factors at play. Rather than viewing and treating the economy as an ecosystem of creative human persons – each working to create innovative solutions across a complex web of human relationships – we have continued to view the economy as a machine to be hacked or upgraded.

Our planning class has been quick to reach for its typical tools and tricks, never suspecting that human creativity is already hard at work. In our panicked efforts to “do something,” how quickly we forget that many workers are already doing something, responding to their unique circumstances with appropriately tailored tactics, working both individually and collectively in complex and spontaneous ways.

When one hears the stories of such entrepreneurs – some of whom are highlighted by Mackrael – this reality quickly comes into focus. For some, the crisis has led to new growth and independence in their same occupations and industries, freeing them from the constraints of former employers. This has been particularly true for roles targeted by lockdowns, such as personal trainers, hair stylists, and chefs. “This pandemic has helped me blossom,” says hair stylist Ramona Wilmarth, who left her salon and now earns 35% to 45% more money a month now that she is self-employed. “It pushed me to do something I wasn’t really ready for” before.

But the changes go well beyond the service sector. According to firms like Fiverr International – which helps facilitate contract gigs for freelancers in digital marketing, graphic design, and writing – “new U.S. freelance registrations on its website rose 48% year-over-year during the July-through-September quarter.” Freelancers have also averaged higher incomes than in years past.

For others, the disruption has provided a nudge to do something new altogether. Mackrael highlights a variety of these stories, from a former DJ who now plans and organizes virtual weddings and concerts to a restaurant worker who stumbled into his own mobile car wash service. “I’m glad I lost the restaurant job,” says the latter. “This pandemic helped me. I used it like a springboard.”

This isn’t to gloss over the damage and destruction caused by the lockdowns. The economic pain is still real and widespread, and much of it could have been avoided with a bit more prudence and restraint. With the continued uncertainty surrounding forthcoming government interventions and the spread of the virus itself, we have a long way to go to revive and repair what has already been broken.

But given America’s apparent revival of “entrepreneurial mojo,” we also have reason for optimism. Far from being crushed by outside pressures, America’s workers continue to innovate and press forward, demonstrating remarkable persistence, resiliency, and ingenuity.

In doing so, they remind the rest of us of the inherent, God-given dignity and creative capacity of the human person – features that will always endure, not fading nor deteriorating according to whatever extreme crises or political dysfunction may surround us.