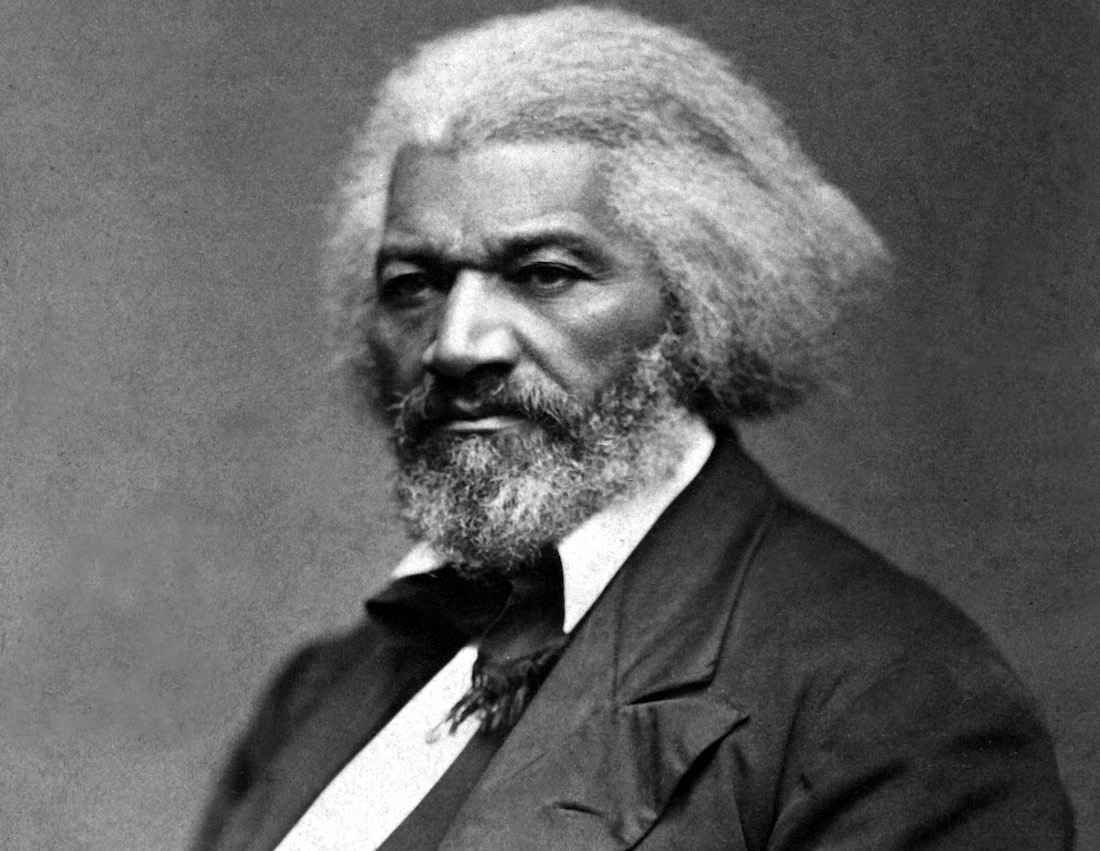

In January 1862, Frederick Douglass, a former slave who became America’s greatest sociopolitical prophet of the nineteenth century, declared that America was facing Armageddon. “The fate of the greatest of all Modern Republics trembles in the balance.” God was in control of the nations, and America was particularly a subject of His providence. “We are taught as with the emphasis of an earthquake,” Douglass told his listeners at Philadelphia’s National Hall, “that nations, not less than individuals, are subjects of the moral government of the universe, and that … persistent transgressions of the laws of this Divine government will certainly bring national sorrow, shame, suffering and death.” Douglass was describing America during the Civil War. In his mind the war was God’s way of providing atonement for America’s great sin – slavery. If white Americans repented of this great sin, the nation could experience a rebirth. “You and I know that the mission of this war is National regeneration,” he told audiences from city to city across the North in 1864. But the nation had to pass through “fire” for the new birth to begin.

According to Douglass’ biographer David Blight, this idea of national covenant was central to Douglass’ long career as America’s principal prophet. “For the story in which to embed the experience of American slaves, [Douglass] reached for the Old Testament Hebrew prophets of the sixth to eighth centuries B.C. … Their awesome narratives of destruction and apocalyptic renewal, exile and return, provided scriptural basis for his mission to convince Americans they must undergo the same.” In innumerable speeches and extensive writings, Douglass exhorted Americans to recognize that God was treating them as he had treated ancient Israel. Just as Israel was exiled when it broke the covenant by egregious sin, so America was exiled because of her “national sin” of slavery. Exile took the form of war and continued conflict. Return from exile would come in the form of peace and reconciliation between the races, but only if America truly repented and performed works befitting repentance.

Even if national repentance was barely beginning when Douglass died in 1895, the national covenant tradition helped him make sense of America’s tortured history with slavery and its aftermath. National covenant is a trope with a long history stretching back to early Christianity. It is not too much to say that for most of the last 2,000 years, most Christians have believed in the national covenant. This is the idea that (a) God deals with whole nations as nations; and (b) He enters into more intimate relationships with societies that claim Him as Lord. In other words, God not only deals with individuals during their lives and at the final judgment but also deals providentially with every corporate people and enters into special relationship with certain whole societies. Those who are familiar with the Bible know that God dealt with biblical Israel as a whole society. But most moderns are probably unaware that the God of Israel also suggested that he entered into relationship with other nations: “‘Are you not like the Cushites to me, O people of Israel?’ declares the Lord. ‘Did I not bring up Israel from the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor and the Syrians from Kir?’” (Amos 9:7).

Most moderns have lost sight of the national covenant, but most premoderns were familiar with it. They would have acknowledged the first part of the tradition, that God blesses and punishes whole nations according to the ways they have responded to “the work of the law … written on their hearts” (Romans 2:15). Nations that uphold the general principles of justice revealed in that “work of the law” – often called “natural law” – are blessed over the long run, and those that flout those principles are eventually punished. These principles roughly correspond to what the Bible calls the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20; Deuteronomy 5).

Here, perhaps, is where the national covenant can help. It says that God can forgive and heal not only an individual but a whole society. The Bible says that God appeared to Solomon in the night and declared to him, “If my people who are called by my name humble themselves, and pray and seek my face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven and will forgive their sin and heal their land” (II Chronicles 7:14). This vision in the night from God suggests that whole societies can be forgiven and healed. It also suggests that healing depends on people turning to God in freedom and humility. This is the spiritual dimension to our nation’s division that can never be mandated by a government. There is no room for coercion here – only prayer and humility.

This nation is hurting. In many ways it is broken, and racial division is a big part of that brokenness. But there is hope. The source is spiritual, not political. It comes from humility and prayer and seeking God’s face. The God of Israel is Lord, even of this hurting land. Our racial divisions suggest that we have experienced covenantal judgment and exile. But we can also experience covenantal forgiveness and healing.

This excerpt has been adapted from the introduction to Race and Covenant: Recovering the Religious Roots for American Reconciliation.