Herman Cain, the 2012 Republican presidential hopeful and former CEO of Godfather’s Pizza, passed away early Thursday morning at the age of 74. During his meteoric rise from poverty to the heights of the business world, Cain shared his faith in Christ, free markets, and the American dream. A former cancer survivor, he was hospitalized on July 1 for complications from COVID-19. He leaves behind his wife, the former Gloria Etchison, and two children: Melanie and Vincent.

Cain was born on December 13, 1945, in Memphis, Tennessee, the son of two hard-working parents. “My great grandparents were sharecroppers. My grandparents were farmers,” he said. His father worked three jobs at once, while his mother also worked — all in menial professions (janitor, barber, and chauffer; and maid, respectively). His family moved to Atlanta when he was a child, where his father, Luther, chauffeured the president of the Coca-Cola Company. “Most generations want to give the next generation a better start,” Cain said. “That’s what my parents tried to do for me.”

The younger Cain rose from the segregated South through his superior intellect and hours poring over books. Cain graduated with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Morehouse College in 1967 and a master’s degree in computer science from Purdue University in 1971. He worked as a civilian employee for the Navy — “he was literally a rocket scientist,” a former employee wrote — before working his way up through the fast food industry. He worked for Pillsbury, which owned Burger King at the time. He became regional vice president over 400 Burger King restaurants, but only after completing a thorough training that began with making burgers and cleaning the restrooms. That taught him the importance of tailoring every aspect of the business to the customer experience.

He became best known for turning around Godfather’s Pizza, which was hemorrhaging money when he became CEO in 1986. He listened to customer feedback and returned the chain to its core mission of service. With those changes came profits. Cain had the franchise in the black within 14 months. He humbly credited his rapid success to “marketing,” but he was the one crafting the strategy and meeting his consumers’ needs. Along the way, Cain also served in the Kansas City Federal Reserve from 1992 to 1996, rising to chairman.

Herman Cain first came to national prominence when he politely confronted then-President Bill Clinton at a 1994 town hall meeting dedicated to Clinton’s proposed health care plan. Although they disagreed, Cain spoke in a respectful and engaging way. His speech intended to educate and persuade President Clinton (who, nevertheless, persisted).

Cain’s measured, masterful, self-assured performance made him a Republican Party star. He caught the attention of many party leaders, including Jack Kemp, who — ever interested in expanding opportunity to minority neighborhoods — befriended Cain and spent hours at a time discussing the finer points of free-market economics. Cain would get an insider’s view of Washington as an economic adviser to the ill-fated Bob Dole/Jack Kemp presidential campaign of 1996. The same year, Cain left the pizza business to lead the National Restaurant Association until 1999.

Cain made a brief foray into presidential politics in 2000, before endorsing Steve Forbes. He ran in the Republican primary for the U.S. Senate seat in Georgia, losing to Johnny Isakson.

He entered the toughest battle of his life in 2006, when doctors diagnosed him with stage 4 colon cancer, saying it had metastasized to his liver. He treated his ailing body as he did his ailing franchise: aggressively. Although he had less than a one-in-three chance of survival, he went into remission.

He emerged in time to be present at the creation of the Tea Party movement. He spoke at its rallies and broadcast its message on Atlanta radio. For a moment, he became its favored standard bearer. Cain declared his candidacy for president of the United States. In October 2011, he shocked politicos by finishing first in a national poll, becoming the first African American to do so in the GOP.

Cain climbed to the top of the pack with another piece of ingenious marketing: His “9-9-9 Plan” called for a flat tax of 9% across the board on income, business, and a new national sales tax. Cain, an associate pastor at Antioch Baptist Church in Atlanta, invoked the biblical concept of the tithe to promote his plan. “If 10% is good enough for God,” he said, “then 9% should be just fine for the federal government.” Proponents said a national sales tax would stimulate economic growth; opponents said politicians in Washington would see it as another revenue stream for their already excessive spending. Whatever the plan’s merits or demerits, Arthur Laffer wrote in the Wall Street Journal that Cain deserved credit for reminding Americans that “the sole purpose of the tax code was to raise the necessary funds to run government,” not “income redistribution, encouraging favored industries, and discouraging unfavorable behavior.”

Cain also rooted his message in returning the nation to the voluntary face-to-face service he found rooted in the Bible. Jesus, he once wrote, was “the perfect conservative”:

He helped the poor without one government program. He healed the sick without a government health care system. He feed the hungry without food stamps. And everywhere He went, it turned into a rally, attracting large crowds, and giving them hope, encouragement and inspiration.

Yet Cain’s presidential aspirations plummeted as quickly as they rose. The candidate made verbal missteps on abortion (which he had always opposed without exception) and had a foggy moment when discussing Barack Obama’s unauthorized military action in Libya. He acknowledged he had once supported the bailouts at the heart of the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP). Ultimately, he suspended his campaign in December 2011 after allegations of sexual harassment, which he had settled out of court and dismissed as “baseless.”

Cain returned to talk radio and sometimes had his name floated for government positions. President Donald Trump selected Cain for a term as one of the seven governors of the Federal Reserve in April 2019, but the nomination disappeared as it became clear Cain lacked requisite support.

Through it all, Cain’s business acumen never wavered. The editor of his website remembered Cain’s generosity in donating his time to shore up his freelancing business. “Ever the dealmaker, he would fill me in with details of his negotiations with people on any number of things,” wrote Dan Calabrese. “I would always tell him I should have him negotiate my deals with my business’s other clients, because he did them better than anyone.”

More than anything, Cain saw himself as a communicator. He had just filmed the first episode of a new Netflix series when he took ill.

His 2012 campaign spokeswoman, Ellen Caramichael, tweeted that Cain’s “American Dream story is one for the history books.” He “[o]vercame absolute destitution, genuine discrimination, stage IV cancer and so much hardship in between. Rose up the ranks of America’s biggest corporations, advised presidential campaigns, chaired a Federal Reserve bank.”

Cain saw himself as living proof that the American Dream of rising through hard work still existed. He dedicated his life to sharing the market orientation, mechanisms, and moral code necessary to succeed. “In the end, what Cain wanted was for other people to be as successful as he had had been in the world of business,” writes Sean Higgins at the Competitive Enterprise Institute.

But he wanted more than that, too. Calabrese wrote:

Romans 2:6-7 says: “God ‘will repay each person according to what they have done.’ To those who by persistence in doing good seek glory, honor and immortality, he will give eternal life.” By that measure, we expect the boss is in for some kind of welcome, because all of us who knew him are well aware of how much good he did.

May his words prove true. Requiescat in pace.

Herman Cain, RIP.

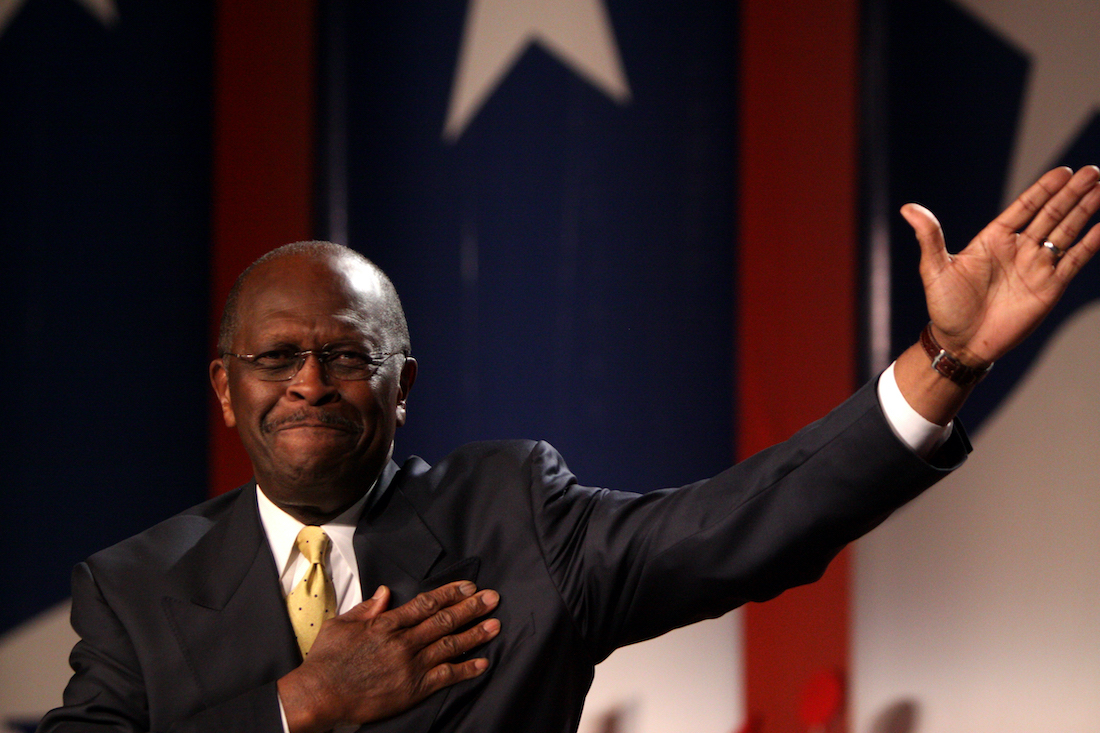

(Photo credit: Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0.)