This is the seventh in a series of essays on Peter Drucker’s early works.

In his 1942 book, The Future of Industrial Man, Peter Drucker pointed to the Christian anthropology of man as a promising building block for society.

He credited Christianity with the idea that men are more alike in their moral character than in their race, nationality, and color. Though we are imperfect and sinful, we are simultaneously made in God’s image and are responsible for our choices. We cannot claim to have fully comprehended the good, but neither can we deny our responsibility to seek it. Freedom, according to Drucker, is based upon faith.

He went on to make a claim that would be surprising to the legions who follow his managerial thought even to this day:

Freedom, as we understand it, is inconceivable outside and before the Christian era. The history of freedom does not begin with Plato or Aristotle. Neither could have visualized any rights of the individual against society, although Aristotle came closer than any man in the pre-Christian era to the creed that man is inherently imperfect and impermanent. Nor does the history of freedom begin with those Athenian “totalitarian liberals,” the Sophists who denied all responsibility of the individual because they denied the existence of absolutes.

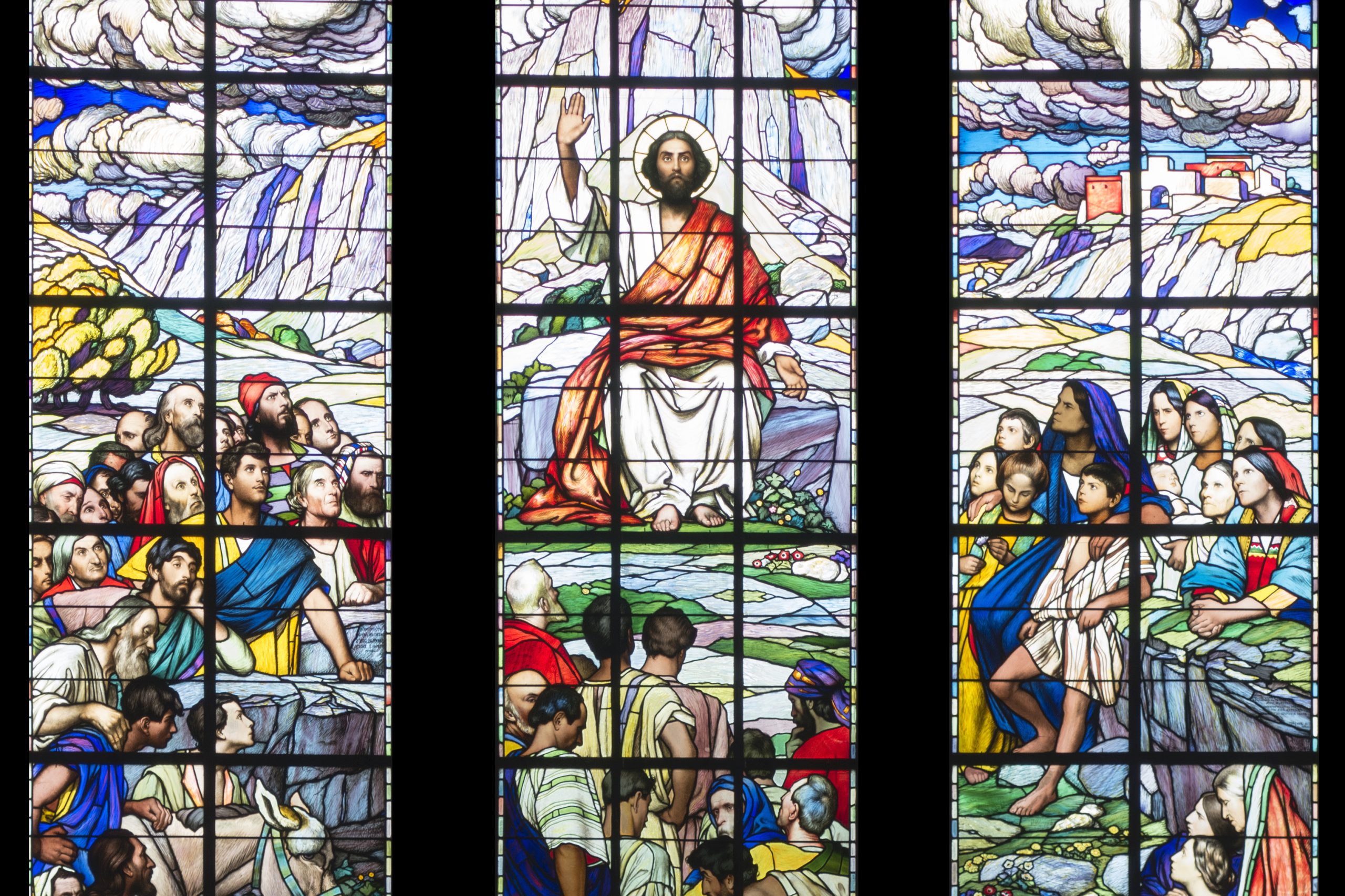

The roots of freedom are in the Sermon on the Mount and in the Epistles of St. Paul; the first flower of the tree of liberty was St. Augustine. But after two thousand years of development from these roots we still have trouble in understanding that freedom is a question of decision and responsibility, not one of perfection and efficiency. In other words, we still confuse only too often the Platonic question: what is the best government? with the Christian question: what is a free society? (italics added)

Those who take what Drucker calls the Christian question “what is a free society?” as their beginning point realize that government and society should be organized as different spheres. The one is limited by the other.

Madison, Jefferson, Burke, and Hamilton saw that there should be a separation of government in the political sphere from social rule. Augustine did it first. The City of God is separate from, but within, the City of Man. See also the theory of the two swords of emperor and church or, more basic still, “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and to the Lord what is the Lord’s.” Caesar’s domain is not comprehensive. In the Christian view of things, it cannot be comprehensive.

It is a mistake, then, to fuse government and society in the form of the political authority. Fundamentally, the point is that the political should never become coextensive with the social. The political options should always lag behind the more organic social counterparts.

Obviously, there are other modern views which proceed from different starting points. The Enlightenment discovery (the French Enlightenment, it would seem), per Drucker, was that human reason is absolute. That attitude helps to explain Robespierre and his Goddess of Reason. Rationalists believe living men can possess perfected, absolute reason. That belief energizes government ambition and action, especially over against what is considered a superstitious worldview.

Americans, Drucker insisted, retained an emphasis on man’s fallen nature. Their liberalism was based on humility, love, and faith. Accordingly, they were less willing to invest institutions with European confidence in the combination of rationality and government power. For Americans, it was safer to draw lines between the political and the social, lest the first overwhelm the second and take freedom with it.

This post is excerpted from a longer article published by the author in the Sept./Oct. 2014 issue of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity.